(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The “RNA world” hypothesis proposes that the earliest life on Earth may have been based on RNA — a single-stranded molecule similar in many ways to DNA — like some modern viruses. This is because, like DNA, RNA can carry genetic information, but, like a protein, it can also act as an enzyme, initiating or accelerating reactions. While the activity of a few RNA enzymes — called ribozymes — have been tested on a case-by-case basis, there are thousands more that have been computationally predicted to exist in organisms ranging from bacteria to plants and animals. Now, a new method, developed by Penn State researchers, can test the activity of thousands of these predicted ribozymes in a single experiment.

The research team tested the activity of over 2,600 different RNA sequences predicted to belong to a class of RNA enzymes called “twister ribozymes,” which have the ability to cut themselves in two. Approximately 94% of the tested ribozymes were active, and the study revealed that their function can persist even when their structure contains slight imperfections. The research team also identified the first example of a twister ribozyme in mammals, specifically in the genome of the bottlenose dolphin.

A paper describing the study appeared online today, Nov. 5, in the journal Nucleic Acids Research.

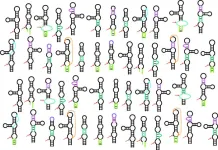

“Whereas DNA is a double-stranded molecule that typically forms a simple helical structure, RNA is single stranded and can fold back on itself, forming diverse structures, including loops, bulges and helixes,” said Phil Bevilacqua, distinguished professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology in the Eberly College of Science at Penn State and the leader of the research team. “The function of RNA enzymes is based on these structures and they have been categorized into several different classes. We chose to focus on so-called ‘twister ribozymes’ because one of their functions is to cleave themselves in two, which we can see by determining their genetic sequence.”

Prior to this study, about 1,600 twister ribozymes had been proposed based on their genomic sequence and predictions of their structure, but only a handful had been experimentally validated. The team developed an experimental pipeline that allowed them to assess the self-cleaving activity of thousands of these ribozymes in a single experiment, which they call a “Cleavage High-Throughput Assay,” or CHiTA. They also identified approximately 1,000 additional twister ribozyme candidates by meticulously hand-searching the genomic context around a short, highly conserved sequence shared by many of the ribozymes in the genomes of 1,000s of organisms.

CHiTA relies on two key factors. One is a recently developed technology called “massively parallel oligonucleotide synthesis,” or MPOS. MPOS gives the research team the ability to design and then purchase thousands of diverse ribozyme sequences in the form of small pieces of DNA, all in a single vial. Each of the sequences they design has as its core one of the 2,600 predicted ribozyme sequences. The researchers then add short bits of DNA at either end that allow them to make copies of the DNA and transcribe it into RNA to test its activity.

“With MPOS, we can simply create a spreadsheet with the sequences that we are interested in, send it to a commercial vendor, and they send us back a tube that contains a small amount of each sequence,” said Lauren McKinley, a graduate student at Penn State at the time of the research, who recently earned a doctorate, and first author of the paper. “For CHiTA, we need lots of each sequence, so we add bits of DNA to each end of the sequences that allows us to make millions of copies of each using a technique called PCR, but these additional bits could impact our ability to test the ribozymes’ functions.”

The second key factor for CHiTA helps to overcome this hurdle by removing these added bits of sequence using a protein — called a restriction enzyme — that cuts DNA at specific short sequences called recognition sites. However, most restriction enzymes cut the DNA somewhere near the middle of their recognition sites, leaving a portion of the recognition site sequence attached to the two resulting DNA fragments that could still impact ribozyme structure and function.

“We found a restriction enzyme that cuts the DNA a short distance from its recognition site, so we could design our sequences such that it would cut leaving no trace of additional DNA,” McKinley said. “This way we could ensure that we were assessing the function of the precise sequence of the ribozymes.”

In the lab, the team first makes additional copies of the sequences ordered through MPOS, trims any additional DNA with the restriction enzyme, and then they can transcribe RNA from the DNA sequences. If any of the sequences codes for active ribozymes, as the RNA is produced, they will quickly fold into their functional structure and cleave themselves. The researchers can then collect the RNA and convert it back to DNA — called cDNA — so that they can read its sequence to see if it is full length or if it’s been cleaved.

“When we sequence the cDNA, we can see how much of the RNA, if any, has been cleaved as an indicator of ribozyme activity,” McKinley said. “For about 94% of the sequences we tested, a significant portion of the RNA was cleaved. In fact, the percentage of each active ribozyme that was cleaved is quite similar to earlier efforts that tested ribozymes individually.”

The team then looked at predicted structures of the sequences they tested and saw that many of them had slight variations or imperfections compared to the canonical twister ribozyme structure, yet they still self-cleaved. This suggested to the researchers that the function of the ribozymes is very tolerant to slight structural changes, meaning they could still operate even if not perfectly formed.

Tolerance of imperfections suggests that there may be more twisters hidden in nature that wouldn’t be found using the original search parameters, according to the team. In fact, new descriptors based on sequences in this study led the research team to discover the first mammalian twister ribozyme, which was identified in the genome of the bottlenose dolphin.

“Understanding these types of tolerances to sequence and structural variation in ribozymes will help us to design new and rigorous ways to identify them,” Bevilacqua said. “Our current knowledge of ribozyme function is mostly based on chemistry, and we are only just beginning to learn about their role in biology. Being able to test their activity in a large-scale assay like CHiTA will hopefully accelerate our ability to find new ribozymes and better understand the role they play in the cell. All of this can also help us to work backwards in time to see what could have been possible when RNA’s ability to do it all might have been a key to jumpstarting life on the early Earth.”

In addition to Bevilacqua and McKinley, the research team at Penn State included McCauley O. Meyer, Aswathy Sebastian and Kyle J. Messina, all of whom were graduate students at the time of the research and have since completed their doctorates; former undergraduate student Benjamin K. Chang; and Research Professor of Bioinformatics Istvan Albert. The National Institutes of Health and the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences funded this research.

END

Testing thousands of RNA enzymes helps find first ‘twister ribozyme’ in mammals

2024-11-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Groundbreaking study provides new evidence of when Earth was slushy

2024-11-05

At the end of the last global ice age, the deep-frozen Earth reached a built-in limit of climate change and thawed into a slushy planet.

Results from a Virginia Tech-led study provide the first direct geochemical evidence of the slushy planet — otherwise known as the “plumeworld ocean” era — when sky-high carbon dioxide levels forced the frozen Earth into a massive, rapid melting period.

“Our results have important implications for understanding how Earth's climate and ocean chemistry changed after the extreme conditions of the last global ...

International survey of more than 1600 biomedical researchers on the perceived causes of irreproducibility of research results

2024-11-05

International survey of more than 1600 biomedical researchers on the perceived causes of irreproducibility of research results

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002870

Article Title: Biomedical researchers’ perspectives on the reproducibility of research

Author Countries: Canada, Australia, United States

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. END ...

Integrating data from different experimental approaches into one model is challenging – this study presents a community-based, full-scale in silico model of the rat hippocampal CA1 region that integra

2024-11-05

Integrating data from different experimental approaches into one model is challenging – this study presents a community-based, full-scale in silico model of the rat hippocampal CA1 region that integrates diverse experimental data from synapse to network

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002861

Article Title: Community-based reconstruction ...

SwRI awarded grant to characterize Las Moras Springs watershed

2024-11-05

SAN ANTONIO — November 5, 2024 — Hydrologists at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) will begin a 12-month targeted water-sampling campaign of the Las Moras Springs system near Brackettville, Texas. The project will analyze and characterize the system of springs and their relationship to the Pinto Creek watershed to improve water management and conservation efforts.

“Las Moras, like many other Texas spring systems, are at-risk and prone to going dry. It is important to clear up uncertainties about their source and relationship with ...

Water overuse in MATOPIBA could mean failure to meet up to 40% of local demand for crop irrigation

2024-11-05

Considered one of the fastest-growing agricultural frontiers in Brazil, and the area with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in the Cerrado, Brazil’s savanna-type biome, the region known as MATOPIBA risks facing water shortages in the years ahead. Water overuse may mean that between 30% and 40% of demand for crop irrigation cannot be met in the period 2025-40. MATOPIBA is a portmanteau of the names of four states – Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia (all but Tocantins located in Brazil’s Northeast ...

An extra year of education does not protect against brain aging

2024-11-05

Thanks to a 'natural experiment' involving 30,000 people, researchers at Radboud university medical center were able to determine very precisely what an extra year of education does to the brain in the long term. To their surprise, they found no effect on brain structure and no protective benefit of additional education against brain aging.

It is well-known that education has many positive effects. People who spend more time in school are generally healthier, smarter, and have better jobs and higher incomes than those with less education. However, whether prolonged education actually causes changes in brain structure over the long term ...

Researchers from Uppsala and Magdeburg obtain an ERC Synergy Grant to advance cancer immunotherapy

2024-11-05

Targeting and customizing blood vessels in tumors to increase T cell infiltration and maintain their function may represent the next breakthrough in cancer therapy. The European Research Council has recognized this by awarding a prestigious Synergy Grant to the project VASC-IMMUNE, where three researchers, each possessing complementary expertise in this research topic, will synergize to advance the field. Professors Anna Dimberg and Magnus Essand are both from the Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University and Professor Thomas Tüting is from the Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Magdeburg.

The successful implementation ...

Deaf male mosquitoes don’t mate

2024-11-05

Mosquitoes are much more blunt. Mating occurs for a few seconds in midair. And all it takes to woo a male is the sound of a female’s wingbeats. Imagine researchers’ surprise when a single change completely killed the mosquitoes’ libidos.

Now a study out of UC Santa Barbara reveals that this is really all there is to it. Researchers in Professor Craig Montell’s lab created deaf mosquitoes and found that the males had absolutely no interest in mating. “You could leave them together with the females ...

Recognizing traumatic brain injury as a chronic condition fosters better care over the survivor’s lifetime

2024-11-05

INDIANAPOLIS – A commentary, published in the Journal of Neurotrauma, calls for traumatic brain injury to be recognized as a chronic condition as are diabetes, asthma, depression and heart failure.

To provide comprehensive care for traumatic brain injury throughout individuals’ lifespans, the authors propose that coordinated care models they and others have developed, tested and applied to various populations -- including older adults, individuals living with depression and post-intensive care unit survivors -- be adapted to improve communication and integration between brain injury specialists -- including ...

SwRI’s Dr. James Walker receives Distinguished Scientist Award from Hypervelocity Impact Society

2024-11-05

SAN ANTONIO — November 5, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute’s Dr. James Walker has received the Distinguished Scientist Award from the Hypervelocity Impact Society. This honor recognizes individuals who have made a significant and lasting contribution to the field of hypervelocity science. Hypervelocity impact is typically viewed as impacts at speeds above 2 kilometers per second (4,475 miles per hour); for some materials, however, lower speed impacts display hypervelocity impact effects.

The ...