(Press-News.org) A new study highlights how some marine life could face extinction over the next century, if human-induced global warming worsens.

The research, led by the University of Bristol and published today in Nature, compares for the first time how tiny ocean organisms called plankton responded, when the world last warmed significantly in ancient history with what is likely to happen under similar conditions by the end of our century.

Findings revealed the plankton were unable to keep pace with the current speed of temperature rises, putting huge swathes of marine life – including fish which depend on these organisms for food – in peril.

Lead author Dr Rui Ying, who led the project as part of his PhD in marine ecology at the University of Bristol, said: “The results are alarming as even with the more conservative climate projections of a 2°C increase, it is clear plankton cannot adjust quickly enough to match the much faster rate of warming which we’re experiencing now and looks set to continue.

“Plankton are the lifeblood of the oceans, supporting the marine food web and carbon storage. If their existence is endangered, it will present an unprecedented threat, disrupting the whole marine ecosystem with devastating wide-reaching consequences for marine life and also human food supplies.”

To reach this conclusion, the researchers developed a new model which allowed analysis of how plankton behaved some 21,000 years ago during the last Ice Age to be analysed alongside how they might act under future climate projections. By focusing on a specific plankton group which has existed throughout the ages, the modelling work offers unprecedented insights and levels of accuracy.

Dr Ying said: “The past is often considered key to understanding what the world could look like in future. Geological records showed that plankton previously relocated away from the warmer oceans to survive.

“But using the same model of ecology and climate, projections showed the current and future rate of warming was too great for this to be possible again, potentially wiping out the precious organisms.”

Under The Paris Agreement, 196 nations agreed to limit the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and strive to limit the increase to 1.5°C. But a United Nations report last month warned the world faces as much as 3.1°C warming if governments do not take more action to reduce carbon emissions.

Co-author Daniela Schmidt, Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, is a world-renowned marine ecologist who has led multiple Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports.

Prof Schmidt said: “This work emphasises the great risks posed by the dramatically fast climate and environmental changes the world is now facing. With these worrying trends set to worsen, there will be very real consequences for our ecosystems and people’s livelihoods, including fishing communities. So the message is clear – all nations must collectively and individually step up efforts and measures to keep global warming to a minimum.”

Paper

‘Past foraminiferal acclimatization capacity is limited during future warming’ in Nature by Rui Ying, Fanny M. Monteiro, Jamie D. Wilson, Malin Ödalen and Daniela N. Schmidt

Notes to editors

Dr Rui Ying and Professor Daniela Schmidt are available for interview and advance copies of the paper can be requested. Please contact Victoria Tagg, Media & PR Manager (Research): victoria.tagg@bristol.ac.uk

Link to paper when embargo lifts:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08029-0

END

Pioneering research shows sea life will struggle to survive future global warming

2024-11-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

In 10 seconds, an AI model detects cancerous brain tumor often missed during surgery

2024-11-13

Researchers have developed an AI powered model that — in 10 seconds — can determine during surgery if any part of a cancerous brain tumor that could be removed remains, a study published in Nature suggests.

The technology, called FastGlioma, outperformed conventional methods for identifying what remains of a tumor by a wide margin, according to the research team led by University of Michigan and University of California San Francisco.

“FastGlioma is an artificial intelligence-based diagnostic system that has the potential to change the field of neurosurgery ...

Burden of RSV–associated hospitalizations in US adults, October 2016 to September 2023

2024-11-13

About The Study: In this cross-sectional study of adults hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) before the 2023 introduction of RSV vaccines, RSV was associated with substantial burden of hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and in-hospital deaths in adults, with the highest rates occurring in adults 75 years or older. Increasing RSV vaccination of older adults has the potential to reduce associated hospitalizations and severe clinical outcomes.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Fiona P. Havers, MHS, MD, email fhavers@cdc.gov.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For ...

Repurposing semaglutide and liraglutide for alcohol use disorder

2024-11-13

About The Study: Among patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and comorbid obesity/type 2 diabetes, the use of semaglutide and liraglutide were associated with a substantially decreased risk of hospitalization due to AUD. This risk was lower than that of officially approved AUD medications. Semaglutide and liraglutide may be effective in the treatment of AUD, and clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm these findings.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Markku Lähteenvuo, MD, PhD, email markku.lahteenvuo@uef.fi.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link ...

IPK-led research team provides insights into the pangenome of barley

2024-11-13

Reliable crop yields fueled the rise of human civilizations. As people embraced a new way of life, cultivated plants, too, had to adapt to the needs of their domesticators. There are different adaptive requirements in a wild compared to an arable habitat. Crop plants and their wild progenitors differ, for example, in how many vegetative branches they initiate or how many seeds or fruits they produce and when.

A common concern among crop conservationists is dangerously reduced genetic diversity in cultivated plants. But crop evolution needs not be a unidirectional loss of diversity. “Our panel of 1,000 plant genetic ...

New route to fluorochemicals: fluorspar activated in water under mild conditions

2024-11-13

Researchers at Oxford University have developed a new method to extract fluorine from fluorspar (CaF₂) using oxalic acid and a fluorophilic Lewis acid in water under mild reaction conditions.

This technology enables direct access to fluorochemicals, including commonly used fluorinating agents, from both fluorspar and lower-grade metspar, eliminating reliance on the supply chain of hazardous hydrogen fluoride (HF).

The findings are published today in the journal Nature.

Currently, all fluorochemicals – critical for many industries – are generated from the highly dangerous mineral acid ...

Microbial load can influence disease associations

2024-11-13

In sickness or in health, the billions of microorganisms that inhabit our guts are our constant companions throughout life. In the past few decades, scientists have shown how the nature of this ‘microbiome’ can provide valuable clues to human diseases and their treatment.

A new study from the Bork group at EMBL Heidelberg, recently published in the journal Cell, reports that a number of conditions, such as lifestyle and disease, affect the total number of microbes in the gut, making this often neglected metric one that bears ...

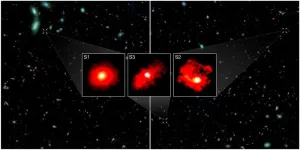

Three galactic “red monsters” in the early Universe

2024-11-13

An international team led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has identified three ultra-massive galaxies – nearly as massive as the Milky Way – already in place within the first billion years after the Big Bang. This surprising discovery was made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope's FRESCO program, which uses the NIRCam/grism spectrograph to measure accurate distances and stellar masses of galaxies. The results indicate that the formation of stars in the early Universe was far more efficient than previously thought, challenging existing galaxy formation models. The study is published in Nature.

In the theoretical model favored by scientists, galaxies form ...

First ever study finds sexual and gender minority physicians and residents have higher levels of burnout, lower professional fulfillment

2024-11-13

EMBARGOED by JAMA Network Open until 11 a.m., ET until Nov. 13, 2024

Contact: Gina DiGravio, 617-358-7838, ginad@bu.edu

(Boston)—Burnout is a public health crisis that affects the well-being of physicians and other healthcare workers, and the populations they serve. Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, lack of motivation, and feelings of ineffectiveness and inadequate achievement at work. Past studies have shown that compared to the general working U.S. population, physicians ...

Astronomers discover mysterious ‘Red Monster’ galaxies in the early Universe

2024-11-13

An international team that was led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and includes Professor Stijn Wuyts from the University of Bath in the UK has identified three ultra-massive galaxies – each nearly as massive as the Milky Way – that had already assembled within the first billion years after the Big Bang.

The researchers’ results indicate that the formation of stars in the early Universe was far more efficient than previously thought, challenging existing galaxy formation models.

The surprising discovery – described today in the journal Nature – was made by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) ...

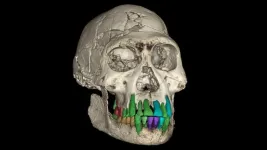

The secrets of fossil teeth revealed by the synchrotron: a long childhood is the prelude to the evolution of a large brain

2024-11-13

The secrets of fossil teeth revealed by the synchrotron: a long childhood is the prelude to the evolution of a large brain

Could social bonds be the key to human big brains? A study of the fossil teeth of early Homo from Georgia dating back 1.77 million years reveals, thanks to the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble, a prolonged childhood despite a small brain and an adulthood comparable to that of the great apes. This discovery suggests that an extended childhood, combined with cultural transmission ...