Could social bonds be the key to human big brains? A study of the fossil teeth of early Homo from Georgia dating back 1.77 million years reveals, thanks to the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble, a prolonged childhood despite a small brain and an adulthood comparable to that of the great apes. This discovery suggests that an extended childhood, combined with cultural transmission in three-generation social groups, may have triggered the evolution of a large brain like that of modern humans, rather than the reverse. The study is published in Nature.

Summary

An international team of researchers from the University of Zurich (Switzerland), the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France), and the Georgian National Museum (Georgia) has challenged the hypothesis that the long childhood of modern humans (Homo sapiens) is linked to their big brains, by studying a fossil of early Homo from Georgia dating back 1.77 million years. Using synchrotron imaging to analyse the dental development of an almost adult individual, the scientists observed that although this species reached adulthood as quickly as the great apes (around 12 years), it exhibited a sequence of tooth development similar to that of modern humans, suggesting a longer duration of childhood, and longer dependence on adults, than in the great apes.

Because the brain of early Homo was only slightly larger than that of a chimpanzee, the researchers hypothesise that this slower development was linked to the intensified cultural transmission across the generations, where the elders pass on their knowledge to the young. A longer childhood in a three-generation social context would have enabled immature group members to assimilate a growing amount of knowledge more effectively. Once this evolutionary process had been set in motion, natural selection would have acted on the traits that made cultural transmission within social groups increasingly efficient. Only in a second phase, and with increasing social information transfer, evolution would have favoured the development of ever-larger brains, which would have led to the late adulthood and long life spans characteristic of modern humans. This study published in Nature demystifies the role of large brains for the evolution of a long childhood, suggesting instead that the long childhood together with the three-generation social structure eventually led to larger brains.

Full text

Compared to the great apes, humans have an exceptionally long childhood, during which parents, grandparents and other adults contribute to their physical and cognitive development. This is a key developmental period for acquiring all the cognitive skills needed in the complex social environment of a human group. The current consensus is that the very long growth of modern humans has evolved as a consequence of the increase in brain volume, since such an organ requires significant energy resources to grow. However, the ‘big brain - long childhood’ hypothesis may need to be revised, as shown by an international team of researchers in the journal Nature, based on an analysis of the dental growth of an exceptional fossil.

Teeth are the key

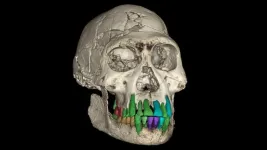

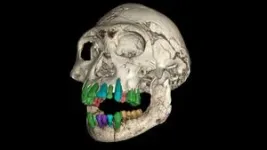

The research team, made up of scientists from the University of Zurich (Switzerland), the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France), and the Georgian National Museum (Georgia), used synchrotron imaging to study the dental development of a near-adult fossil of early Homo from the Dmanisi site in Georgia, dated to around 1.77 million years ago.

“Childhood and cognition do not fossilise, so we have to rely on indirect information. Teeth are ideal because they fossilise well and produce daily rings, in the same way that trees produce annual rings, which record their development”, explains Christoph Zollikofer from the University of Zurich and first author of the publication. “Dental development is strongly correlated with the development of the rest of the body, including brain development. Access to the details of a fossil hominid's dental growth therefore provides a great deal of information about its general growth”, adds Paul Tafforeau, scientist at the ESRF and co-author of the study.

18 years of research

The project was launched in 2005, following the initial success of non-destructive analyses of dental microstructures using phase contrast synchrotron tomography at the ESRF. This technique enabled scientists to create virtual microscopic slices through the teeth of this fossil. The exceptional quality of preservation of the growth structures in this specimen has made it possible to reconstruct all the phases of its dental growth, from birth to death, with unprecedented precision. In a way, the scientists have virtually regrown the teeth of this hominid.

This project took almost 18 years from its initial conception in 2005 to the finalisation of the results in 2023. The scientists scanned the teeth for the first time in 2006, and the first results on the fossil’s age at death were obtained in 2007.

“We expected to find either dental development typical of early hominids, close to that of the great apes, or dental development close to that of modern humans. When we obtained the first results, we couldn’t believe what we saw, because it was something different that implied faster molar crown growth than in any other fossil hominin or living great ape”, explains Paul Tafforeau. Over the next few years, five series of experiments and four complete analyses using different approaches were carried out as technical advances were made in dental synchrotron imaging. With the results all pointing in the same direction, and potentially having a strong impact on the ‘big brain - long childhood’ hypothesis, the scientists had to think outside the box to understand this fossil. “It's been a slow maturation, both technically and intellectually, to finally arrive at the hypothesis we are publishing today” concludes Paul Tafforeau.

Milk teeth used for longer

“The results showed that this individual died between 11 and 12 years of age, when his wisdom teeth had already erupted, as is the case in great apes at this age,” explains Vincent Beyrand, co-author of the study. However, the team found that this fossil had a surprisingly similar tooth maturation pattern to humans, with the back teeth lagging behind the front teeth for the first five years of their development.

“This suggests that milk teeth were used for longer than in the great apes and that the children of this early Homo species were dependent on adult support for longer than those of the great apes,” explains Marcia Ponce de León from the University of Zurich and co-author of the study. “This could be the first evolutionary experiment of prolonged childhood”.

How teeth can give clues about brain evolution

This is where the ‘big brain - long childhood’ hypothesis is put to the test. Early Homo individuals did not have much bigger brains than great apes or australopithecines, but they possibly lived longer. In fact, one of the skulls discovered at Dmanisi was that of a very old individual with no teeth left during its last few years of life. “The fact that such an old individual was able to survive without any teeth for several years indicates that the rest of the group took good care of him,” comments David Lordkipadnize of the National Museum of Georgia and co-author of the study. The older individuals are the ones with the greatest experience, so it's likely that their role in the community was to pass on their knowledge to the younger individuals. This three-generation structure is a fundamental aspect of the transmission of culture in humans.

It is well known that young children can memorise an enormous amount of information thanks to the plasticity of their immature brains. However, the more there is to memorise, the longer it takes.

This is where the new hypothesis comes in. Children's growth would have slowed down at the same time as cultural transmission increased, making the amount of information communicated from old to young increasingly important. This transmission would have enabled them to make better use of available resources while developing more complex behaviours, and would thus have given them an evolutionary advantage in favour of a longer childhood (and probably of a longer lifespan).

Once this mechanism was in place, natural selection would have acted on cultural transmission and not just to biological traits. Then, as the amount of information to be transmitted increased, evolution would have favoured an increase in brain size and a delay in adulthood, allowing us both to learn more in childhood and to have the time to grow a larger brain despite limited food resources.

Therefore, it may not have been the evolutionary increase in brain size that led to the slowdown in human development, but the extension of childhood and the three-generation structure that favoured bio-cultural evolution. These mechanisms, in turn, led to an increase in brain size, a later adulthood and a longer life span. Studying the teeth of this exceptional fossil could therefore encourage researchers to reconsider the evolutionary mechanisms that led to our own species, Homo sapiens.

Reference: 'Dental evidence for extended growth in early Homo from Dmanisi', Nature, 13 November 2024, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08205-2

Scientist contacts:

Paul Tafforeau, ESRF scientist (French, English), paul.tafforeau@esrf.fr

Christoph Zollikofer, scientist, Dept. of informatics, University of Zurich (German, English, French), zolli@ifi.uzh.ch

Marcia Ponce de León, scientist, Dept. of Informatics, University of Zurich, (Spanish, English, German, French), marcia@ifi.uzh.ch

END