(Press-News.org) The origin of many diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's can be found at the molecular level in our body, in other words, in proteins. In a healthy system, these proteins are responsible for numerous physiological functions. In order to carry out certain tasks, they may also assemble in groups consisting of numerous proteins. Once that job is done, they split up again and go their own ways. However, if larger clusters of a hundred or more proteins form so-called fibrils, which are bundles of long, filament-like accumulations of proteins, the attraction between the proteins is so strong that they can no longer separate from each other. The resultant plaques can induce a wide variety of disorders. If the fibrils accumulate in the brain, for instance, they can increase intracranial pressure, thus triggering neurodegenerative diseases.

Disintegration of fibrils achieved for the first time

The formation of fibrils is generally an irreversible process, both in the human body and in synthetic systems. Professor Shikha Dhiman of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) in Germany and Professor Lu Su of Leiden University in the Netherlands have recently succeeded in creating a model system in which fibrils can be broken down into their individual components or liquid droplets. The project also involved two Ph.D. students, Mohit Kumar in Mainz and Heleen Duijs in Leiden. "This is the first model system in which we have succeeded in reversing this process without any chemical reaction," reported Dhiman.

Within fibrils, non-covalent bonds – such as hydrogen bridges – link the single units together. These are not particularly robust on their own, but it is the high number of bonds and their order that gives fibrils their superior stability. The researchers thus decided to use a bit of trick: They added substances that embed themselves in fibrils creating pocket-like formations that make the fibril structure unstable. "What we are in effect doing is introducing competing binding partners. These form bonds with single units, the interaction between units become redundant, and the fibrils begin to disintegrate", explained Dhiman.

Model system allows for systematic investigations

A particularly interesting feature of the model system is that it allows all parameters that can be modified to be systematically studied one by one. Until recently, researchers had assumed that individual proteins come together to form fibrils. Recently, however, this concept has been disproved. Rather, several proteins accumulate together with water and salts resulting in liquid droplets, with the proteins arranging themselves on the surface of these droplets. This is a significant intermediate state in the actual formation of fibrils. In contrast with fibrils, these droplets can undertake normal functions in the body and can even break up to release the proteins again. "Our model system has been able to map all three states, namely individual single units, liquid droplets, and fibrils," explained Shikha Dhiman, Professor at the JGU Department of Chemistry and senior researcher in the CoM2Life research network, with which JGU is applying for funding as a Cluster of Excellence in the German national Excellence Strategy competition. CoM2Life is the abbreviation for "Communicating Biomaterials: Convergence Center for Life-Like Soft Materials and Biological Systems".

Fundamental basis for the development of innovative therapies

In the long term, the model system will support the development of drugs to treat a range of disorders, particularly neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Unlike in complex systems such as cells, all parameters of the model system can be readily explored to answer various questions: What causes protein droplets to clump together to form fibrils? How can this process be regulated? How can fibrils be broken down into short fibers? Once the researchers have resolved these fundamental issues, they can investigate the cellular level – based on large-scale screening of active substances. "The potential in terms of therapeutic applications is enormous," emphasized Lu Su, Assistant Professor at the Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research. "We expect that drugs developed on the basis of this model will be used for the targeted disintegration of pathological fibrils to alleviate symptoms and improve outcomes for patients."

END

New model system for the development of potential active substances used in condensate modifying drugs

Researchers at the universities in Mainz and Leiden have developed a simple model system that can be used to break down fibrils – the cause of numerous disorders including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease – into their constituent single units or li

2024-11-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How to reduce social media stress by leaning in instead of logging off

2024-11-13

Young people’s mental health may depend on how they use social media, rather than how much time they spend using it, according to a new study by University of B.C. researchers.

The research, led by psychology professor Dr. Amori Mikami (she/her) and published this week in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, examined the effects of quitting social media versus using it more intentionally.

The results showed that users who thoughtfully managed their online interactions, as well as those who abstained from social media entirely, saw mental health benefits—particularly in reducing symptoms ...

Pioneering research shows sea life will struggle to survive future global warming

2024-11-13

A new study highlights how some marine life could face extinction over the next century, if human-induced global warming worsens.

The research, led by the University of Bristol and published today in Nature, compares for the first time how tiny ocean organisms called plankton responded, when the world last warmed significantly in ancient history with what is likely to happen under similar conditions by the end of our century.

Findings revealed the plankton were unable to keep pace with the current speed of temperature rises, putting huge swathes ...

In 10 seconds, an AI model detects cancerous brain tumor often missed during surgery

2024-11-13

Researchers have developed an AI powered model that — in 10 seconds — can determine during surgery if any part of a cancerous brain tumor that could be removed remains, a study published in Nature suggests.

The technology, called FastGlioma, outperformed conventional methods for identifying what remains of a tumor by a wide margin, according to the research team led by University of Michigan and University of California San Francisco.

“FastGlioma is an artificial intelligence-based diagnostic system that has the potential to change the field of neurosurgery ...

Burden of RSV–associated hospitalizations in US adults, October 2016 to September 2023

2024-11-13

About The Study: In this cross-sectional study of adults hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) before the 2023 introduction of RSV vaccines, RSV was associated with substantial burden of hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and in-hospital deaths in adults, with the highest rates occurring in adults 75 years or older. Increasing RSV vaccination of older adults has the potential to reduce associated hospitalizations and severe clinical outcomes.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Fiona P. Havers, MHS, MD, email fhavers@cdc.gov.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For ...

Repurposing semaglutide and liraglutide for alcohol use disorder

2024-11-13

About The Study: Among patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and comorbid obesity/type 2 diabetes, the use of semaglutide and liraglutide were associated with a substantially decreased risk of hospitalization due to AUD. This risk was lower than that of officially approved AUD medications. Semaglutide and liraglutide may be effective in the treatment of AUD, and clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm these findings.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Markku Lähteenvuo, MD, PhD, email markku.lahteenvuo@uef.fi.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link ...

IPK-led research team provides insights into the pangenome of barley

2024-11-13

Reliable crop yields fueled the rise of human civilizations. As people embraced a new way of life, cultivated plants, too, had to adapt to the needs of their domesticators. There are different adaptive requirements in a wild compared to an arable habitat. Crop plants and their wild progenitors differ, for example, in how many vegetative branches they initiate or how many seeds or fruits they produce and when.

A common concern among crop conservationists is dangerously reduced genetic diversity in cultivated plants. But crop evolution needs not be a unidirectional loss of diversity. “Our panel of 1,000 plant genetic ...

New route to fluorochemicals: fluorspar activated in water under mild conditions

2024-11-13

Researchers at Oxford University have developed a new method to extract fluorine from fluorspar (CaF₂) using oxalic acid and a fluorophilic Lewis acid in water under mild reaction conditions.

This technology enables direct access to fluorochemicals, including commonly used fluorinating agents, from both fluorspar and lower-grade metspar, eliminating reliance on the supply chain of hazardous hydrogen fluoride (HF).

The findings are published today in the journal Nature.

Currently, all fluorochemicals – critical for many industries – are generated from the highly dangerous mineral acid ...

Microbial load can influence disease associations

2024-11-13

In sickness or in health, the billions of microorganisms that inhabit our guts are our constant companions throughout life. In the past few decades, scientists have shown how the nature of this ‘microbiome’ can provide valuable clues to human diseases and their treatment.

A new study from the Bork group at EMBL Heidelberg, recently published in the journal Cell, reports that a number of conditions, such as lifestyle and disease, affect the total number of microbes in the gut, making this often neglected metric one that bears ...

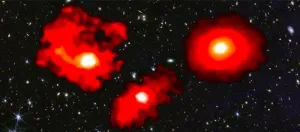

Three galactic “red monsters” in the early Universe

2024-11-13

An international team led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has identified three ultra-massive galaxies – nearly as massive as the Milky Way – already in place within the first billion years after the Big Bang. This surprising discovery was made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope's FRESCO program, which uses the NIRCam/grism spectrograph to measure accurate distances and stellar masses of galaxies. The results indicate that the formation of stars in the early Universe was far more efficient than previously thought, challenging existing galaxy formation models. The study is published in Nature.

In the theoretical model favored by scientists, galaxies form ...

First ever study finds sexual and gender minority physicians and residents have higher levels of burnout, lower professional fulfillment

2024-11-13

EMBARGOED by JAMA Network Open until 11 a.m., ET until Nov. 13, 2024

Contact: Gina DiGravio, 617-358-7838, ginad@bu.edu

(Boston)—Burnout is a public health crisis that affects the well-being of physicians and other healthcare workers, and the populations they serve. Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, lack of motivation, and feelings of ineffectiveness and inadequate achievement at work. Past studies have shown that compared to the general working U.S. population, physicians ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] New model system for the development of potential active substances used in condensate modifying drugsResearchers at the universities in Mainz and Leiden have developed a simple model system that can be used to break down fibrils – the cause of numerous disorders including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease – into their constituent single units or li