(Press-News.org) A new study shows land in California’s San Joaquin Valley has been sinking at record-breaking rates over the last two decades as groundwater extraction has outpaced natural recharge.

The researchers found that the average rate of sinking for the entire valley reached nearly an inch per year between 2006 and 2022.

Researchers and water managers have known that sinking, technically termed “subsidence,” was occurring over the past 20 years. But the true impact was not fully appreciated because the total subsidence had not been quantified. This was in part due to a gap in data. Satellite radar systems, which provide the most precise measure of elevation changes, did not consistently monitor the San Joaquin Valley between 2011 and 2015. The Stanford researchers have now estimated how much the land sank during these four years.

“Our study is the first attempt to really quantify the full Valley-scale extent of subsidence over the last two decades,” said senior study author Rosemary Knight, a professor of geophysics in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “With these findings, we can look at the big picture of mitigating this record-breaking subsidence.”

The new study, published Nov. 19 in Communications Earth and Environment, offers ideas on how to stop the sinking through strategic regional water recharge and other management approaches.

Rapid and uneven declines in land elevation have forced multimillion-dollar repairs to canals and aqueducts that ferry critical water through the San Joaquin Valley to southern California’s major cities. By damaging local wells and irrigation ditches, this subsidence is also exacerbating water supply issues for one of the most agriculturally productive regions in the world.

“The bill for repairing major aqueducts like the Friant-Kern Canal and the California Aqueduct is exceptionally high,” said lead author Matthew Lees, PhD ’23, a research associate with the University of Manchester who worked on the study as a PhD student in geophysics at Stanford. “But the subsidence is having other effects, too. How much was last year’s flooding worsened by subsidence? How much are farmers spending to re-level their land? A lot of the costs of subsidence aren’t well known.”

History repeating itself

Subsidence occurs as water is removed from natural reservoirs called aquifers, where water is stored in underground sediments including sand, gravel, and clay. Like a sponge, the sediments are full of pores. As those spaces are emptied, the sediments compact – in some cases permanently, altering future water-carrying capacity – and cause the ground level to fall.

In the San Joaquin Valley, which runs from east of the San Francisco Bay Area down to the mountains north of Los Angeles, booming agriculture and population growth prompted aggressive pumping of groundwater between 1925 and 1970. The result: More than 4,000 square miles – an area half the size of New Jersey – sank by over 12 inches, reaching about 30 feet in some locations, a profound landscape change that a 1999 governmental report described as “one of the single largest alterations of the land surface attributed to humankind.”

The problem ebbed during the 1970s following the installation of new aqueducts. But it roared back in the early 2000s amid a series of droughts, intensified groundwater pumping, land-use changes, and reduced deliveries from Northern California rivers. “There are two astonishing things about the subsidence in the valley. First, is the magnitude of what occurred prior to 1970. And second, is that it is happening again today,” said Knight.

Understanding the problem

To gauge the recent subsidence rate, Lees and Knight turned to a technique known as interferometric synthetic aperture radar, or InSAR. The technique captures elevation changes across roughly football field-size chunks of land as frequently now as a few times per month by beaming radar signals from orbit. The signals reflect off the ground back to the satellites, and analysis of the received signal reveals changes in ground elevation.

The InSAR data record for the San Joaquin Valley is patchy between 2011 and 2015, due to limited satellite coverage. To fill this gap, Lees and Knight used elevation data from Global Positioning System (GPS) stations scattered throughout the region. They identified spatial patterns in the InSAR record and used these to interpolate elevation in the vast areas between GPS stations.

Additional analysis by the researchers suggests that San Joaquin Valley aquifers require approximately 220 billion gallons of water coming in each year – through natural or engineered processes – to prevent future subsidence.

This is about 7 billion gallons less than the amount of surface water left over in the San Joaquin Valley in an average year after all environmental needs are covered. “I am optimistic that we can do something about subsidence,” said Knight. “My group and others have been studying this problem for some time, and this study is a key piece in figuring out how to sustainably address it.”

Replenishing aquifers to prevent sinking

A water management approach called flood-managed aquifer recharge (flood-MAR), which is being widely adopted in California, could help. It involves diverting excess surface water from precipitation and snowmelt to locations where the water can percolate down and recharge aquifers.

Drenching the whole of the Valley via flood-MAR water is not feasible. “We should be targeting the places where subsidence will cause the greatest social and economic costs,” said Knight. “So, we look at places where subsidence is going to damage an aqueduct or domestic wells in small communities, for instance.”

“By taking this Valley-scale perspective,” added Knight, “we can start to get our head around viable solutions.”

Acknowledgements

Knight is also a senior fellow in the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

The research was funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and NASA.

END

Groundwater pumping drives rapid sinking in California

2024-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Neuroscientists discover how the brain slows anxious breathing

2024-11-19

LA JOLLA (November 19, 2024)—Deep breath in, slow breath out… Isn’t it odd that we can self-soothe by slowing down our breathing? Humans have long used slow breathing to regulate their emotions, and practices like yoga and mindfulness have even popularized formal techniques like box breathing. Still, there has been little scientific understanding of how the brain consciously controls our breathing and whether this actually has a direct effect on our anxiety and emotional state.

Neuroscientists ...

New ion speed record holds potential for faster battery charging, biosensing

2024-11-19

PULLMAN, Wash. – A speed record has been broken using nanoscience, which could lead to a host of new advances, including improved battery charging, biosensing, soft robotics and neuromorphic computing.

Scientists at Washington State University and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have discovered a way to make ions move more than ten times faster in mixed organic ion-electronic conductors. These conductors combine the advantages of the ion signaling used by many biological systems, including the human body, with the electron signaling used by computers.

The new development, detailed in the journal ...

Haut.AI explores the potential of AI-enhanced fluorescence photography for non-invasive skin diagnostics

2024-11-19

Tallinn, Estonia – 19th November 2024, 10 AM CET – Haut.AI, a pioneering artificial intelligence (AI) company for skincare and beauty applications, has published an exciting scientific review—one that explores state-of-the-art developments in skin fluorescence photography and its applications, focusing on combining it with AI algorithms for non-invasive skin diagnostics. The study highlights the power of AI to enhance skin fluorescence photography, allowing early, non-invasive detection of skin conditions. This approach allows skincare experts to diagnose underlying issues ...

7-year study reveals plastic fragments from all over the globe are rising rapidly in the North Pacific Garbage Patch

2024-11-19

A study published today in IOP Publishing’s journal Environmental Research Letters reveals that centimetre-sized plastic fragments are increasing much faster than larger floating plastics in the North Pacific Garbage Patch [NPGP], threatening the local ecosystem and potentially the global carbon cycle.

The research, which draws from not-for-profit The Ocean Cleanup’s systematic surveys of the NPGP between 2015 and 2022, found an unexpected rise in mass concentration of plastic fragments that are ...

New theory reveals the shape of a single photon

2024-11-19

A new theory, that explains how light and matter interact at the quantum level has enabled researchers to define for the first time the precise shape of a single photon.

Research at the University of Birmingham, published in Physical Review Letters, explores the nature of photons (individual particles of light) in unprecedented detail to show how they are emitted by atoms or molecules and shaped by their environment.

The nature of this interaction leads to infinite possibilities for light to exist and propagate, or travel, through its surrounding environment. This limitless ...

We could soon use AI to detect brain tumors

2024-11-19

A new paper in Biology Methods and Protocols, published by Oxford University Press, shows that scientists can train artificial intelligence models to distinguish brain tumors from healthy tissue. AI models can already find brain tumors in MRI images almost as well as a human radiologist.

Researchers have made sustained progress in artificial intelligence (AI) for use in medicine. AI is particularly promising in radiology, where waiting for technicians to process medical images can delay patient treatment. Convolutional neural networks are powerful tools that allow researchers to train AI models on large image datasets to recognize ...

TAMEST recognizes Lyda Hill and Lyda Hill Philanthropies with Kay Bailey Hutchison Distinguished Service Award

2024-11-19

TAMEST is pleased to announce Lyda Hill and Lyda Hill Philanthropies as the recipients of the Kay Bailey Hutchison Distinguished Service Award.

TAMEST is recognizing Lyda Hill and her team for empowering and enabling groundbreaking research in science and nature that profoundly impacts society. Lyda Hill, a successful businesswoman and world-renowned philanthropist, believes science can solve many of the world’s most challenging issues and has chosen to donate all of her estate to philanthropy and scientific research.

Aligned with this mission, Lyda Hill is committed to advancing science and public ...

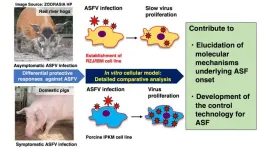

Establishment of an immortalized red river hog blood-derived macrophage cell line

2024-11-19

Red river hogs (RRHs) (Potamochoerus porcus), a wild species of Suidae living in Africa, have grabbed much attention as an animal that harbors African swine fever virus (ASFV) as natural hosts. When ASFV infects domestic pigs and wild boars, it proliferates within macrophages, a type of immune cells, and infected pigs rapidly die suffering from symptoms such as fever and hemorrhage. On the other hand, ASFV infection in RRHs is asymptomatic and does not cause death, suggesting that RRH macrophages may have a protective mechanism against ASFV infection.

In vitro cell cultures of porcine macrophages are generally ...

Neural networks: You might not need to buy every ticket to win the lottery

2024-11-19

The more lottery tickets you buy, the higher your chances of winning, but spending more than you win is obviously not a wise strategy. Something similar happens in AI powered by deep learning: we know that the larger a neural network is (i.e., the more parameters it has), the better it can learn the task we set for it. However, the strategy of making it infinitely large during training is not only impossible but also extremely inefficient. Scientists have tried to imitate the way biological brains learn, which is highly resource-efficient, by providing machines with a gradual training process that starts with ...

Healthy New Town: Revitalizing neighborhoods in the wake of aging populations

2024-11-19

Planned suburban residential neighborhoods in metropolitan areas known as new towns were initially developed in England. The new town movement spread from Europe to East Asia, such as to Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. In Japan alone, 2,903 New Towns were built, but many experienced rapid population decline and aging in the 40 years after their development. Therefore, they changed into old new towns and had to transform their facilities.

Dr. Haruka Kato, a junior associate professor at Osaka Metropolitan ...