(Press-News.org) Laboratory experiments with cancer cells reveal two ways in which tumors evade drugs designed to starve and kill them, a new study shows.

While chemotherapies successfully treat cancers and extend patients’ lives, they are known not to work for everyone for long, as cancer cells rewire the process by which they convert fuel into energy (metabolism) to outmaneuver the drugs’ effects. Many of these drugs are so-called antimetabolics, disrupting cell processes needed for tumor growth and survival.

Three such drugs used in the study — raltitrexed, N-(phosphonacetyl)-l-aspartate (PALA), and brequinar — work to prevent cancer cells from making pyrimidines, molecules that are an essential component to genetic letter codes, or nucleotides, that make up RNA and DNA. Cancer cells must have access to pyrimidine supplies to produce more cancer cells and to produce uridine nucleotides, a primary fuel source for cancer cells as they rapidly reproduce, grow, and die. Disrupting the fast-paced but fragile pyrimidine synthesis pathways, as some chemotherapies are designed to do, can rapidly starve cancer cells and spontaneously lead to them dying (apoptosis).

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health and its Perlmutter Cancer Center, the new study shows how cancer cells survive in an environment made hostile by the persistent shortage of the energy from glucose (the chemical term for blood sugar) needed to drive tumor growth. This better understanding of how cancer cells evade the drugs’ attempts to kill them in a low-glucose environment, the researchers say, could lead to the design of better or more effective combination therapies.

Publishing in the journal Nature Metabolism online Nov. 26, study results showed that the low-glucose environment inhabited by cancer cells, or tumor microenvironment, stalls cancer cell consumption of existing uridine nucleotide stores, making the chemotherapies less effective.

Normally, uridine nucleotides would be made and consumed to help make the genetic letter codes and fuel cell metabolism. But when DNA and RNA construction is blocked by these chemotherapies, so too is the consumption of uridine nucleotide pools, the researchers found, as glucose is needed to change one form of uridine, UTP, into another usable form, UDP-glucose. The irony, researchers say, is that a low-glucose tumor microenvironment is in turn slowing down cellular consumption of uridine nucleotides and presumably slowing down rates of cell death. Researchers say cancer cells need to run out of pyrimidine building blocks, including uridine nucleotides, before the cells will self-destruct.

In other experiments, low-glucose tumor microenvironments were also unable to activate two proteins, BAX and BAK, sitting on the surface of mitochondria, a cell’s fuel generator. Activation of these trigger proteins disintegrates the mitochondria, and instantly sets off a series of caspase enzymes that help initiate apoptosis (cell death).

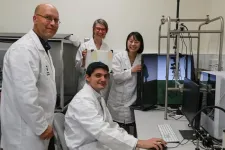

“Our study shows how cancer cells manage to offset the impact of low-glucose tumor microenvironments, and how these changes in cancer cell metabolism minimize chemotherapy’s effectiveness,” said study lead investigator Minwoo Nam, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Pathology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Perlmutter Cancer Center.

“Our results explain what has until now been unclear about how the altered metabolism of the tumor microenvironment impacts chemotherapy: low glucose slows down the consumption and exhaustion of uridine nucleotides needed to fuel cancer cell growth and hinders resulting apoptosis, or death, in cancer cells,” said senior study investigator Richard Possemato, PhD. Possemato is an associate professor in the Department of Pathology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and also a member of Perlmutter Cancer Center.

Possemato, who is also coleader of the Cancer Cell Biology Program at Perlmutter, says his team’s study results could one day be used to develop chemotherapies or combination therapies that would change or trick cancer cells into responding the same way in a low-glucose microenvironment as they would in an otherwise stable glucose microenvironment.

He also says that diagnostic tests could be developed to measure how a patient’s cancer cells would most likely respond to low-glucose microenvironments and to predict how well a patient might respond to a particular chemotherapy.

Possemato says his team has plans to investigate how blocking other cancer cell pathways might trigger apoptosis in response to these chemotherapies. Some experimental drugs, such as Chk-1 and ATR inhibitors, already exist that might accomplish this, he notes, but more need to be investigated because Chk-1 and ATR inhibitors are not well tolerated by patients.

For the study, researchers performed a scan of 3,000 cancer cell genes known to be involved in cell metabolism to determine, by deletion, which were necessary for cancer cell survival after chemotherapy. Most of the genes they found that were essential to cell survival in low-glucose tumor environments were also involved in pyrimidine synthesis, a precise biological pathway targeted by many chemotherapies. This focused their experiments on how different lab-grown clones of cancer cells responded to low-glucose after chemotherapy and what other chemical processes were impacted by depressed sugar levels.

Funding support for the study was provided by National Institutes of Health grants P30CA016087, R01CA286141, R01CA214948, R01GM132491, R35GM139610. Additional funding support came from the Pew Charitable Trusts, Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust, and the American Cancer Society.

Besides Nam and Possemato, other NYU Langone researchers involved in this study are co-investigators Wenxin Xia, Abdul Hannan Mir, and Tony Huang.

Media Inquiries:

David March

212-404-3528

David.March@nyulangone.org

END

Study details how cancer cells fend off starvation and death from chemotherapy

2024-11-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Transformation of UN SDGs only way forward for sustainable development

2024-11-26

Climate change is the single biggest threat to the global environment and socio-economic development – demanding an urgent transformation of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), according to a new study.

The UN SDGs were created to end poverty, build social-economic-health protection and enhance education and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and providing environmental protection.

Following last week’s COP29 environmental summit in Baku, University of Birmingham experts say that, as climate action is linked to sustainable development, systematic integration of climate resilience into every ...

New study reveals genetic drivers of early onset type 2 diabetes in South Asians

2024-11-26

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 10.00AM (UK TIME) ON 26 NOVEMBER 2024

New study reveals genetic drivers of early onset type 2 diabetes in South Asians

Peer reviewed | Observational study | People

A genetic predisposition to having lower insulin production and less healthy fat distribution are major causes of early-onset type 2 diabetes in British Asian people. According to new research from Queen Mary University of London, these genetic factors also lead to quicker development of health complications, earlier need for insulin treatment, and a weaker response ...

Delay and pay: Tipping point costs quadruple after waiting

2024-11-26

RICHLAND, Wash. —Tip the first tile in a line of dominoes and you’ll set off a chain reaction, one tile falling after another. Cross a tipping point in the climate system and, similarly, you might spark a cascading set of consequences like hastened warming, rising sea levels and increasingly extreme weather.

It turns out there’s more to weigh than catastrophic environmental change as tipping points draw near, though. Another point to consider, a new study reveals, is the cost of undoing the damage.

The cost of reversing the effects of climate change—restoring melted polar sea ice, for ...

Magnetic tornado is stirring up the haze at Jupiter's poles

2024-11-26

While Jupiter's Great Red Spot has been a constant feature of the planet for centuries, University of California, Berkeley, astronomers have discovered equally large spots at the planet's north and south poles that appear and disappear seemingly at random.

The Earth-size ovals, which are visible only at ultraviolet wavelengths, are embedded in layers of stratospheric haze that cap the planet's poles. The dark ovals, when seen, are almost always located just below the bright auroral zones at each ...

Cancers grow uniformly throughout their mass

2024-11-26

Researchers at the University of Cologne and the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona have discovered that cancer grows uniformly throughout its mass, rather than at the outer edges. The work, published today in the journal eLIFE, challenges decades-old assumptions about how the disease grows and spreads.

“We challenge the idea that a tumour is a ‘two-speed’ entity with rapidly dividing cells on the surface and slower activity in the core. Instead, we show they are uniformly growing masses, where every region is equally active and has the potential ...

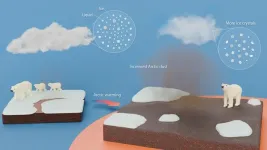

Researchers show complex relationship between Arctic warming and Arctic dust

2024-11-26

The Arctic is warming two to four times faster than the global average. A recent study by researchers in Japan found that dust from snow- and ice-free areas of the Arctic may be an important contributor to climate change in the region. The findings were published in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science.

According to one view, higher temperatures in the Arctic are thought to lead to the region's clouds containing more liquid droplets and fewer ice crystals. Clouds become thicker, longer lasting, ...

Brain test shows that crabs process pain

2024-11-26

Researchers from the University of Gothenburg are the first to prove that painful stimuli are sent to the brain of shore crabs providing more evidence for pain in crustaceans. EEG style measurements show clear neural reactions in the crustacean's brain during mechanical or chemical stimulation.

In the search for a better welfare of animals that we humans kill for food, researchers at the University of Gothenburg have chosen to focus on decapod crustaceans. This includes shellfish delicacies such as prawns, lobsters, crabs and crayfish that we both catch wild and farm. Currently, ...

Social fish with low status are so stressed out it impacts their brains

2024-11-26

Social stress is bad for your brain. It’s a prime suspect in the accumulation of oxidative stress in the brain, which is believed to contribute to mental health and neurodegenerative disorders — but the mechanisms that turn social stress into oxidative stress, and how social status affects this, are poorly understood. By studying a highly social, very hierarchical fish species, cichlids, scientists have now found that social stress raises oxidative stress in the brains of low-status fish.

“We found that low rank was generally linked to higher levels of oxidative stress in the brain,” said Dr Peter Dijkstra of ...

Predicting the weather: New meteorology estimation method aids building efficiency

2024-11-26

Due to the growing reality of global warming and climate change, there is increasing uncertainty around meteorological conditions used in energy assessments of buildings. Existing methods for generating meteorological data do not adequately handle the interdependence of meteorological elements, such as solar radiation, air temperature, and absolute humidity, which are important for calculating energy usage and efficiency.

To address this challenge, a research team at Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Human Life and Ecology—comprising Associate ...

Inside the ‘swat team’ – how insects react to virtual reality gaming

2024-11-26

Humans get a real buzz from the virtual world of gaming and augmented reality but now scientists have trialled the use of these new-age technologies on small animals, to test the reactions of tiny hoverflies and even crabs.

In a bid to comprehend the aerodynamic powers of flying insects and other little-understood animal behaviours, the Flinders University-led study is gaining new perspectives on how invertebrates respond to, interact with and navigate virtual ‘worlds’ created by advanced entertainment technology.

Published in the ...