(Press-News.org) A new study has linked distinct neural and behavioral characteristics in autism spectrum disorder to a simple computational principle. Centered on the “dynamic range” of neurons, which reflects how gradually or sharply they respond to input, the study suggests that individuals with autism spectrum disorder have an increased dynamic range in their neuronal response, resulting in a more detailed but slower response to changes. This research defies previous descriptions of ASD as a “broken cog in the machine” and provides a deeper, richer account of the computational basis of ASD.

[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]– Researchers Dr. Yuval Hart and Oded Wertheimer from the Psychology department and the Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Science (ELSC) at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem have developed a new computational model to explain neural and behavioral differences in autism spectrum disorder. This model offers fresh insights into information processing in the brains of individuals with autism spectrum disorder, opening new avenues for future research and understanding.

Autism spectrum disorder is known to present unique neural and behavioral characteristics compared to neurotypical individuals, but the underlying computational mechanisms remain complex and multifaceted. The model proposed by Dr. Hart and Wertheimer centers around the concept of “dynamic range” within neuronal populations. Dynamic range refers to the range of signals for which neurons elicit discernible responses. In simpler terms, it reflects how gradually or sharply neurons respond to stimuli – a more gradual response entails an increased dynamic range.

"Our model suggests that autism spectrum disorder is not a `broken cog in the machine`, but rather a spectrum of points on the computational tradeoff line between accurate inference and fast adaptation." said Dr. Yuval Hart. "This computational trade-off proved to be a fruitful framework for explaining many of the neural and behavioral characteristics seen in autism."

The researchers found that an increased dynamic range, indicating a gradual response of a neuronal population to changes in input, accounts for neural and behavioral variations in individuals diagnosed with ASD across diverse tasks. This gradual response enables more accurate encoding of details but comes with a trade-off: slower adaptation to changes. By contrast, a narrower dynamic range allows for quick, threshold-based reactions, facilitating fast adaptation but potentially at the expense of fine discrimination.

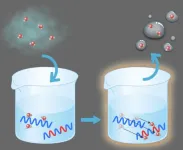

Testing their model across diverse simulations and behavioral tasks, including finger-tapping synchronization, orientation reproduction, and global motion coherence, the researchers demonstrated that increased dynamic range might underlie certain autism spectrum disorder-related behaviors. This variation in response could stem from differences in how individual neurons activate. For instance, increased variability in individual neurons’ half-activation point, the point where the neuron’s response is half of its maximal value, could lead to a broader dynamic range at the population level, influencing how sensory input is processed and interpreted by the brain.

"We show how heterogeneity in the half-activation points of single neurons can result in a more gradual population response and can thus lead to an increased dynamic range." explained Oded Wertheimer. "Given the vast literature that maps autism spectrum disorder to mutations in genes related to neuronal receptors, the proposed biological mechanism is highly relevant – many sources of heterogeneity in these neuronal features can lead to increased dynamic range. This model provides a new lens for understanding autism spectrum disorder, one that bridges biological mechanisms at the neuronal level with computational principles."

Dr. Hart and Wertheimer’s findings also provide insight into why autism spectrum disorder research often yields conflicting results. Differences in the dynamic range within the autism spectrum disorder population may contribute to the variation in findings across studies, highlighting the need for larger participant groups to ensure robust results.

Their model aligns with existing theories that relate autism spectrum disorder to atypical sensory processing, supporting a connection to broader biological and genetic factors. Specific genetic mutations associated with autism spectrum disorder, such as those affecting synaptic regulation, may contribute to this increased dynamic range. These biological factors could lead to a more variable neuronal response, creating the nuanced, analog-like encoding seen in autism spectrum disorder individuals.

By exploring this computational trade-off, the study not only introduces a new perspective on autism spectrum disorder but also suggests future directions for study. The researchers propose that examining this dynamic range at different developmental stages, or through animal models, could further clarify its impact on autism spectrum disorder-related behaviors.

END

Autism and neural dynamic range: insights into slower, more detailed processing

2024-11-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI can predict study results better than human experts

2024-11-27

Large language models, a type of AI that analyses text, can predict the results of proposed neuroscience studies more accurately than human experts, finds a new study led by UCL (University College London) researchers.

The findings, published in Nature Human Behaviour, demonstrate that large language models (LLMs) trained on vast datasets of text can distil patterns from scientific literature, enabling them to forecast scientific outcomes with superhuman accuracy.

The researchers say this highlights ...

Brain stimulation effectiveness tied to learning ability, not age

2024-11-27

As we age, our cognitive and motor functions deteriorate, which in turn affects our independence and overall quality of life. Research efforts to ameliorate or even completely abolish this have given rise to technologies that show a lot of promise.

Among these is non-invasive brain stimulation: a term encompassing a set of techniques that can affect brain functions externally and noninvasively, without the need for surgery or implants. One such promising technique, in particular, is anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (atDCS), which uses ...

Making a difference: Efficient water harvesting from air possible

2024-11-27

Harvesting water from the air and decreasing humidity are crucial to realizing a more comfortable life for humanity. Water-adsorption polymers have been playing a key part in atmospheric water harvesting and desiccant air conditioning, but desorption so that the polymers can be efficiently reused has been an issue. Now, Osaka Metropolitan University researchers have found a way to make desorption of these polymers more efficient.

Usually, heat of around 100°C is required to desorb these polymers, but Graduate School of Engineering student Daisuke Ikegawa, Assistant Professor Arisa Fukatsu, ...

World’s most common heart valve disease linked to insulin resistance in large national study

2024-11-27

A large new population study of men over 45 indicates insulin resistance may be an important risk factor for the development of the world’s most common heart valve disease – aortic stenosis (AS).

Published today in the peer-reviewed journal Annals of Medicine, the findings are believed to be the first to highlight this previously unrecognised risk factor for the disease.

It is hoped that by demonstrating this link between AS and insulin resistance – when cells fail to respond effectively to insulin and the body makes more than necessary to maintain normal glucose ...

Study unravels another piece of the puzzle in how cancer cells may be targeted by the immune system

2024-11-27

Effective immunity hinges on the ability to sense infection and cellular transformation. In humans, there is a specialised molecule on the surface of cells termed MR1. MR1 allows sensing of certain small molecule metabolites derived from cellular and microbial sources; however, the breadth of metabolite sensing is unclear.

Published in PNAS, researchers at the Monash University Biomedicine Discovery Institute have identified a form of Vitamin B6 bound to MR1 as a means of engaging tumour-reactive immune cells. The work involved an international collaborative team co-led by researchers from the University of Melbourne.

According ...

Long-sought structure of powerful anticancer natural product solved by integrated approach

2024-11-27

A collaborative effort by the research groups of Professor Haruhiko Fuwa from Chuo University and Professor Masashi Tsuda from Kochi University has culminated in the structure elucidation and total synthesis of anticancer marine natural products, iriomoteolide-1a and -1b. These natural products were originally isolated from the marine dinoflagellate collected off the Iriomote Island, Okinawa, Japan.

Because of its potent anticancer activity, iriomoteolide-1a is an intriguing natural product that attract immense attention from the chemical community around the globe. ...

World’s oldest lizard wins fossil fight

2024-11-27

A storeroom specimen that changed the origins of modern lizards by millions of years has had its identity confirmed.

The tiny skeleton, unearthed from Triassic-aged rocks in a quarry near Bristol, is at least 205 million years old and the oldest modern-type lizard on record.

Recently, the University of Bristol team’s findings came under question, but fresh analysis, published today in Royal Society Open Science, proves that the fossil is related to modern anguimorphs such as anguids and monitors. The discovery ...

Simple secret to living a longer life

2024-11-27

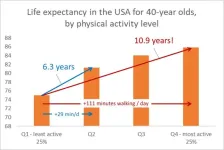

If everyone in the United States population was as active as the top 25 per cent, individuals over the age of 40 could add five years to their life, according to a new study led by Griffith University researchers.

Physical activity has long been known to be good for health, however estimates have varied regarding how much benefit could be gained from a defined amount of activity, both for individuals and for populations.

This latest study used accelerometry to gain an accurate view of the population’s physical activity levels instead of relying on survey responses as per other studies, and found the benefits were around twice as strong ...

Same plant, different tactic: Habitat determines response to climate

2024-11-27

Plants need light to grow, but too much light can induce damage to the photosynthetic complex known as photosystem II. It is known that plants adapted to growing under full sun repair this light-induced damage more. But this repair activity slows down in colder temperatures. An Osaka Metropolitan University-led international research team has now found some clues to how plants survive in colder regions.

Graduate School of Science Associate Professor Riichi Oguchi and colleagues from Australia, Austria, and Japan grew Arabidopsis thaliana (commonly ...

Drinking plenty of water may actually be good for you

2024-11-27

Public health recommendations generally suggest drinking eight cups of water a day. And many people just assume it’s healthy to drink plenty of water.

Now researchers at UC San Francisco have taken a systematic look at the available evidence. They concluded that drinking enough water can help with weight loss and prevent kidney stones, as well as migraines, urinary tract infections and low blood pressure.

“For such a ubiquitous and simple intervention, the evidence hasn’t been clear and the benefits were not well-established, so we wanted to take a closer look,” said senior and corresponding author Benjamin Breyer, MD, MAS, the Taube ...