(Press-News.org) Embargoed for release: Friday, November 29, 2:00 PM ET

Key points:

Exposure to PM2.5 was associated with higher levels of inflammation among pregnant women, potentially leading to adverse birth outcomes.

Study examined PM2.5 and maternal and fetal health on a single-cell level, using an innovative technology to detect how pollution modified the DNA within individual cells.

Findings provide new understanding of the biological pathways through which air pollution affects pregnancy and birth outcomes, and further highlight the importance of policy and clinical interventions to limit air pollution exposure for pregnant women.

Boston, MA—For pregnant women, exposure to fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) was associated with altered immune responses that can lead to adverse birth outcomes, according to a new study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The study is the first to examine the relationship between PM2.5 and maternal and fetal health on a single-cell level and highlights the health risk of PM2.5 exposure for pregnant women.

The study will be published November 29 in Science Advances.

“This study represents a substantial step forward in understanding the biological pathways through which PM2.5 exposure affects pregnancy, maternal health, and fetal development. Its advanced methodology represents a significant innovation for how we study immune responses to environmental exposures,” said corresponding author Kari Nadeau, John Rock Professor of Climate and Population Studies and chair of the Department of Environmental Health.

Previous research has found associations between exposure to PM2.5 and maternal and child health complications including preeclampsia, low birth weight, and developmental delays in early childhood. To understand these associations on a cellular level, the researchers used air quality data collected by the Environmental Protection Agency to calculate study participants’ average PM2.5 exposure. Participants were both non-pregnant women and 20-week pregnant women. The researchers then used an innovative technology to understand how pollution modified the DNA of participants’ individual cells. Within each cell they were able to map changes to histones, the proteins that help control the release of cytokines—proteins that help control inflammation in the body and that can affect pregnancy.

The study found that PM2.5 exposure can influence the histone profiles of pregnant women, disrupting the normal balance of cytokine genes and leading to increased inflammation in both women and fetuses. In pregnant women, this increase in inflammation can correspond with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

“Our findings highlight the importance of minimizing air pollution exposure in pregnant women to protect maternal and fetal health,” said co-author Youn Soo Jung, research associate in the Department of Environmental Health. “Policy interventions to improve air quality, as well as clinical guidelines to help pregnant women reduce their exposure to pollution, could have a direct impact on reducing pregnancy complications.”

Other Harvard Chan authors were Abhinav Kaushik and Mary Johnson.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Science (R01ES032253), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL081521), and the National Institutes of Health/Environmental Protection Agency (EPA R834596/NIEHS P01ES022849, EPA RD835435/NIEHS P20ES018173).

“Impact of air pollution exposure on cytokines and histone modification profiles at single-cell levels during pregnancy,” Youn Soo Jung, Juan Aguilera, Abhinav Kaushik, Ji Won Ha, Stuart Cansdale, Emily Yang, Rizwan Ahmed, Fred Lurmann, Liza Lutzker, S Katherine Hammond, John Balmes, Elizabeth Noth, Trevor D. Burt, Nima Aghaeepour, Anne R. Waldrop, Purvesh Khatri, Paul J. Utz, Yael Rosenburg-Hasson, Rosemarie DeKruyff, Holden T. Maecker, Mary M. Johnson, Kari C. Nadeau, Science Advances, November 29, 2024, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adp5227

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and events from our Studio.

###

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is a community of innovative scientists, practitioners, educators, and students dedicated to improving health and advancing equity so all people can thrive. We research the many factors influencing health and collaborate widely to translate those insights into policies, programs, and practices that prevent disease and promote well-being for people around the world. We also educate thousands of public health leaders a year through our degree programs, postdoctoral training, fellowships, and continuing education courses. Founded in 1913 as America’s first professional training program in public health, the School continues to have an extraordinary impact in fields ranging from infectious disease to environmental justice to health systems and beyond.

END

Fine particulate air pollution may play a role in adverse birth outcomes

2024-11-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sea anemone study shows how animals stay ‘in shape’

2024-11-29

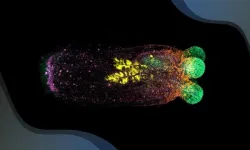

Our bodies are remarkably skilled at adapting to changing environments. For example, whether amid summer heat or a winter freeze, our internal temperature remains steady at 37°C, thanks to a process called homeostasis. This hidden balancing act is vital for survival, enabling animals to maintain stable internal conditions even as the external world shifts. But recent research from the Ikmi Group at EMBL Heidelberg shows that homeostasis can extend beyond internal regulation and actively redefine an organism’s shape.

The starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) possesses remarkable regenerative abilities. Cut off its head ...

KIER unveils catalyst innovations for sustainable turquoise hydrogen solutions

2024-11-29

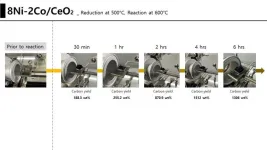

Dr. Woohyun Kim's research team from the Hydrogen Research Department at the Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) has successfully developed an innovative nickel-cobalt composite catalyst that can accelerate the production and commercialization of turquoise hydrogen.*

*Turquoise Hydrogen: A technology that produces hydrogen and carbon by decomposing hydrocarbons such as methane (CH₄) (CH₄ → C + 2H₂). Unlike gray hydrogen, the most widely used hydrogen production technology, ...

Bacteria ditch tags to dodge antibiotics

2024-11-29

Bacteria modify their ribosomes when exposed to widely used antibiotics, according to research published today in Nature Communications. The subtle changes might be enough to alter the binding site of drug targets and constitute a possible new mechanism of antibiotic resistance.

Escherichia coli is a common bacterium which is often harmless but can cause serious infections. The researchers exposed E. coli to streptomycin and kasugamycin, two drugs which treat bacterial infections. Streptomycin has been a staple in treating tuberculosis and other infections since the 1940s, while kasugamycin is less known but crucial in agricultural settings ...

New insights in plant response to high temperatures and drought

2024-11-29

Ghent, 29 November 2024 – We are increasingly confronted with the impacts of climate change, with failed harvests being only one example. Addressing these challenges requires multifaceted approaches, including making plants more resilient. An international research team led by researchers at VIB-UGent has unraveled how the opening and closing of stomata - tiny pores on leaves – is regulated in response to high temperatures and drought. These new insights, published in Nature Plants, pave the way for developing climate change-ready crops.

Global climate change affects more and more people, with extreme weather conditions ...

Strategies for safe and equitable access to water: a catalyst for global peace and security

2024-11-29

Water can be a catalyst for peace and security with a critical role in preventing conflicts and promoting cooperation among communities and nations - but only if managed equitably and sustainably, a new study reveals.

Experts have devised a blueprint to ensure safe, equitable and sustainable global access to clean water. The seven-point strategy will allow water challenges to be governed effectively so they do not create conflict when access is restricted or usage unfairly shared.

Publishing ...

CNIO opens up new research pathways against paediatric cancer Ewing sarcoma by discovering mechanisms that make it more aggressive

2024-11-29

Ewing sarcoma is a tumour of the bones and soft tissues that occurs in children and young people. A quarter of patients do not respond well to therapy.

The group led by Ana Losada, at Spain’s National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), has discovered an alteration in the most aggressive cases that affects genes never previously related to this disease.

This finding expands the list of potential prognostic markers and therapeutic targets in the most aggressive cases of Ewing sarcoma.

The new research is published in EMBO Reports.

Ewing sarcoma is a tumour of the bones and soft tissues that occurs in children and young people. ...

Disease severity staging system for NOTCH3-associated small vessel disease, including CADASIL

2024-11-29

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest the NOTCH3-associated small vessel disease (NOTCH3-SVD) staging system will help to better harmonize NOTCH3-SVD and cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) cohort studies and registries; may improve individualized disease counseling, monitoring, and clinical management; and may facilitate patient stratification in clinical trials.

Corresponding Authors: To contact the corresponding ...

Satellite evidence bolsters case that climate change caused mass elephant die-off

2024-11-29

A new study led by King’s College London has provided further evidence that the deaths of 350 African elephants in Botswana during 2020 were the result of drinking from water holes where toxic algae populations had exploded due to climate change.

The lead author of the report says their analysis shows animals were very likely poisoned by watering holes where toxic blooms of blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, had developed after a very wet year followed a very dry one.

Davide Lomeo, a PhD student in the Department of Geography at King’s College London and co-supervised by Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) and ...

Unique killer whale pod may have acquired special skills to hunt the world’s largest fish

2024-11-29

Killer whales can feed on marine mammals, turtles, and fish. In the Gulf of California, a pod might have picked up new skills that help them hunt whale sharks – the world’s largest fish, growing up to 18 meters long.

Whale sharks feed at aggregation sites in the Gulf of California, sometimes while they are still young and smaller. During this life-stage, they are more vulnerable to predation, and anecdotal evidence suggests orcas could be hunting them. Now, researchers in Mexico have reported four separate hunting events.

“We show how orcas displayed a collaboratively hunting technique on whale sharks, characterized by ...

Emory-led Lancet review highlights racial disparities in sudden cardiac arrest and death among athletes

2024-11-29

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 6:30 PM November 28, 2024:

A recent major review of data published by the Lancet and led by Emory sports cardiologist Jonathan Kim, MD, shows that Black athletes are approximately five times more likely to experience sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) compared to White athletes, despite some evidence of a decline in rates of SCD overall. SCA and SCD have historically been a leading cause of mortality among athletes, particularly those involved in high-intensity sports.

The disparities in SCA/D rates highlights the need for increased research into the social determinants of health in younger athletes, a topic that remains ...