(Press-News.org) UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 00.05 GMT WEDNESDAY 4 DECEMBER / 19:05 ET TUESDAY 3 DECEMBER 2024

Ocean density identified as a key driver of carbon capture by marine plankton

New findings, published today in Royal Society Open Science, have revealed that changes in ocean density have a significant impact on the rate at which marine plankton incorporate carbon into their shells. This has profound implications for carbon cycling and the ocean’s ability to absorb atmospheric CO2 in response to climate change.

Up to now, researchers have focused on how ocean chemistry and acidification affect the biomineralization of marine plankton. This study, led by Dr Stergios Zarkogiannis from the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, breaks new ground by highlighting the critical role of physical ocean properties—specifically density—in influencing this process.

Foraminifera, abundant microscopic shell-bearing organisms, play a pivotal role in the carbon cycle, due to their ability to sequester carbon dioxide into their calcium carbonate shells (a process called calcification). These sink to the ocean floor when they die, contributing to long-term carbon storage. Yet, the factors driving calcification remain poorly understood.

This new study focused on Trilobatus trilobus, an abundant planktonic foraminifera species. The findings reveal that this species is highly sensitive to changes in ocean density and salinity—not just chemistry—and fine-tunes its calcification process in response. A key reason for this is that T. trilobus – similar to other planktonic foraminifera – cannot actively move itself and relies on buoyancy forces (a function of ocean density) to keep its position in the water column.

According to the new results, as ocean density decreases (and buoyancy forces decrease with it), T. trilobus reduces calcification to decrease its weight and stop itself from sinking. This ultimately leaves surface waters more alkaline and increases their ability to absorb CO2.

The results have important implications for climate change. When ice sheets melt, this introduces freshwater into oceans, causing ocean density to decrease. Reduced calcification in less dense waters, anticipated in a future ocean impacted by climate-driven ice sheet melting and freshening, could increase ocean alkalinity and enhance its capacity to absorb CO2. For short-term climatic cycles, increased absorption of CO2 by the oceans would have a greater influence than the reduced incorporation of carbon into planktonic foraminifera (which stores carbon over longer cycles).

Dr Stergios Zarkogiannis said: “Our findings demonstrate how planktonic foraminifera adapt their shell architecture to changes in seawater density. This natural adjustment, potentially regulating atmospheric chemistry for millions of years, underscores the complex interplay between marine life and the global climate system.”

In the study, Dr Zarkogiannis analysed modern (late Holocene) T. trilobus fossil shells collected from deep-sea sediment sites along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the central Atlantic Ocean. Using advanced techniques such as X-ray microcomputed tomography (which rotates specimens to capture thousands of X-ray images), reconstructing them in three dimensions to reveal hidden anatomical details, and shell trace element geochemistry, the study connected calcification patterns to variations in salinity, density, and carbonate chemistry.

The results demonstrated that the species produces thinner, lighter shells in equatorial waters and thicker, heavier shells in the denser subtropical regions.

According Dr Zarkogiannis, the study reframes the narrative around ocean calcification, showing that physical ocean changes, such as density and salinity, play as much of a role as chemical factors do. These findings provide a critical view of how marine ecosystems adapt to climate change.

Dr Zarkogiannis added: “Although planktonic organisms may passively float in the water column, they are far from passive participants in the carbon cycle. By actively adjusting their calcification to control buoyancy and ensure survival, these organisms also regulate the ocean’s ability to absorb CO2. This dual role underscores their profound importance in understanding and addressing climate challenges.”

While this study reveals critical insights into how T. trilobus adapts its calcification, more research is needed to determine whether buoyancy regulation influences calcification in other groups of organisms that contribute to ocean and atmosphere chemistry regulation, such as coccolithophores.

Additionally, it remains unclear whether this is a universal process affecting all planktonic organisms, including those which form shells using silica or organic materials. Future studies by Dr Zarkogiannis will investigate whether these principles apply across diverse groups and oceanic regions.

Notes to editors

For interviews or more information, please contact Dr Stergios D. Zarkogiannis at stergios.zarkogiannis@earth.ox.ac.uk or +44 (0) 7515938853 Images available on request.

The study ‘Calcification and ecological depth preferences of the planktonic foraminifer Trilobatus trilobus in the central Atlantic’ will be published in Royal Society Open Science at 00:05 GMT Wednesday 4 December 2024 / 19:05 ET Tuesday 3 December 2024 at https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.240179 To view a copy of the study before this under embargo, contact Dr Stergios D. Zarkogiannis at stergios.zarkogiannis@earth.ox.ac.uk or +44 (0) 7515938853

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the ninth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

END

Ocean density identified as a key driver of carbon capture by marine plankton

2024-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New drug candidate for spinocerebellar ataxia

2024-12-04

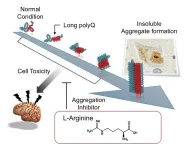

Niigata, Japan - A team led by Specially Appointed Associate Professor Tomohiko Ishihara and Professor Osamu Onodera at Niigata University, along with Professor Yoshitaka Nagai at Kindai University, conducted a randomized, double-blind trial on the efficacy and safety of L-arginine in treating Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6).

I. Background of the Study

Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting the cerebellum, a part of the brain responsible for coordinating movement. Symptoms include difficulties with balance, coordination, and speech (ataxia ...

Small amounts of incidental vigorous physical exertion may almost halve major cardiovascular events risk in women

2024-12-04

Short bursts of incidental vigorous physical exertion, lasting less than a minute each, may almost halve the risk of a major cardiovascular event, such as heart attack or heart failure among women who don’t exercise regularly, finds research published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Just 1.5-4 daily minutes of high intensity routine activities, such as brisk stair climbing or carrying heavy shopping, may help to stave off cardiovascular disease among those either unwilling or unable to take part in structured exercise or sport, conclude the international team ...

Health + financial toll of emerging mosquito-borne chikungunya infection likely vastly underestimated

2024-12-04

The health and financial implications of the emerging threat of mosquito-borne chikungunya viral infection have most likely been significantly underestimated, with total costs probably approaching US$ 50 billion in 2011-20 alone, suggests a comprehensive data analysis, published in the open access journal BMJ Global Health.

In the short term, symptoms include fever, severe joint pain, rash and fatigue. While these often clear up, those affected can be left with long term, debilitating aftereffects, including chronic arthritic-type joint pain, fatigue, and depression, point out the researchers.

The ...

Tiny, daily bursts of vigorous incidental physical activity could almost halve cardiovascular risk in middle-aged women

2024-12-04

An average of four minutes of incidental vigorous physical activity a day could almost halve the risk of major cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks, for middle-aged women who do not engage in structured exercise, according to new research from the University of Sydney, published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

“We found that a minimum of 1.5 minutes to an average of 4 minutes of daily vigorous physical activity, completed in short bursts lasting up to 1 minute, were ...

Long-term benefit from anti-hormonal treatment is influenced by menopausal status

2024-12-04

Today, women with oestrogen-sensitive breast cancer receive anti-hormonal therapy. Researchers now show that postmenopausal women with low-risk tumours have a long-term benefit for at least 20 years, while the benefit was more short-term for younger women with similar tumour characteristics who had not yet gone through the menopause. The results are reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI).

In Sweden, 9 000 women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year, with hormone-sensitive breast cancer accounting for about 75 percent of women diagnosed with the disease. In patients with hormone-sensitive breast cancer tumour growth is mainly driven by oestrogen and ...

Most of growth in high intensity hospital stays not explained by patient details

2024-12-03

In five states over nearly a decade, hospitals have increased how frequently they document patients as needing the highest intensity care, which has led to hospitals receiving billions in extra payments from health plans and government programs, according to a new RAND study.

Among thousands of cases involving hospitals stays for 239 conditions, researchers examined how often hospitals upcoded patients to the sickest end of the care spectrum, where hospitals charge payers at the highest rate.

The study found that from ...

OHSU study in neurosurgery patients reveals numerical concepts are processed deep in ancient part of brain

2024-12-03

New research reveals the unique human ability to conceptualize numbers may be rooted deep within the brain.

Further, the results of the study by Oregon Health & Science University involving neurosurgery patients suggests new possibilities for tapping into those areas to improve learning among people bedeviled by math.

“This work lays the foundation to deeper understanding of number, math and symbol cognition — something that is uniquely human,” said senior author Ahmed Raslan, ...

Predicting cardiac issues in cancer survivors using a serum protein panel test

2024-12-03

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – December 3, 2024) Early disease detection is beneficial for securing the best possible outcomes for patients. But finding noninvasive, effective ways to predict disease risk is a tremendous challenge. Findings from scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital are showing promise for assessing cardiomyopathy risk in childhood cancer survivors. Heart disease is a well-established late effect for pediatric cancer survivors treated with anthracycline chemotherapy. The researchers identified a panel ...

Research on neurodegeneration in spider brain leads Vermont neuroscientists to groundbreaking new discovery in Alzheimer’s-affected human brains

2024-12-03

COLCHESTER, VT – Researchers from Saint Michael’s College and the University of Vermont have made a groundbreaking new discovery that provides a better understanding of how Alzheimer’s disease develops in the human brain.

Guided by previous research of spider brains, the scientists uncovered evidence of a “waste canal system” in the human brain that internalizes waste from healthy neurons. They discovered that this system can undergo catastrophic swelling, which leads to the degeneration of brain tissue, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

With over 50 million affected people worldwide, Alzheimer’s ...

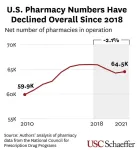

Nearly 1 in 3 retail pharmacies have closed since 2010

2024-12-03

Key study findings:

The rate of pharmacy store closures in recent years has more than doubled, affecting about 1 in 3 pharmacies between 2010 and 2021 and contributing to an unprecedented decline in the availability of pharmacies in the U.S

About one-third of counties experienced an overall decline in pharmacies, and the risk of closure was higher in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Independent pharmacies, often excluded from networks by pharmacy benefit managers, were more than twice as likely to face closure compared to chain pharmacies.

Policymakers should consider several ...