(Press-News.org) The life of billions of people inhabiting Earth is owed to a temporary organ that supported and nourished them in a mother’s womb.

The placenta, or afterbirth, is considered sacred by some cultures, its pivotal role in pregnancy recognized as far back as the raising of Egypt’s pyramids. It provides nutrients and oxygen to the fetus via the umbilical cord, acting like a gut, kidney, liver, and lungs.

If the placenta fails, only one hazardous option remains — premature delivery through induced labor or cesarean delivery.

Now, the first therapy to potentially reverse a condition that is a significant cause of stillbirth and premature delivery around the globe is being developed by a team led by a University of Florida Health researcher who has spent 20 years studying this remarkable organ. The therapy has proved highly successful in animal studies.

Up to 1 in 10 pregnancies in the developed world are affected by placental growth restriction, and twice that in the undeveloped world.

The success of the gene therapy created by UF Health researcher Helen N. Jones, Ph.D., and a team of collaborators would mark a sea change in obstetrics.

Optimistically, human trials are five years in the future.

But Jones, an associate professor in the UF College of Medicine’s Department of Physiology and Aging, said there is good reason for optimism, noting in vitro (outside the body) evidence from the laboratory shows the treatment could be effective in human tissue.

“This is a very exciting therapy,” Jones said. “We’re very happy with our results so far. If this goes well, it could be a game-changer for mothers worldwide. It has the potential to prevent so many premature births and give families hope that placental failure is not the early end of a pregnancy.”

Placental growth insufficiency, which starves the fetus of nutrition and oxygen, leaves doctor and mother with no option to extend a fetus’ time in the womb. Premature delivery can be many weeks before a due date.

“The only thing that can be done is deliver the baby and bring it to the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit),” Jones said.

Even when babies survive birth, often far below normal birth weight, health issues can develop in later years, including neurodevelopmental dysfunction.

The new gene therapy is delivered to the placenta by a polymer nanoparticle so small it would take roughly 500 of them, side by side, to equal the width of a human hair.

The nanoparticle carries cargo — a DNA plasmid. This is a piece of harmless DNA that, introduced into a specific type of cell in the placenta, triggers the manufacture of a protein that interacts with the cell to activate chemical processes that can change or enhance cellular function.

In a sense, the cell receives an extra set of instructions to make more of this protein. That’s crucial because these placentas don’t make enough, leading them to fail.

The cause of placental insufficiency isn’t well understood. One thing scientists have noted, however, is that these malfunctioning placentas have lower levels of a hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1. The gene therapy coaxes the placenta to produce more significant quantities of the growth factor.

This hormone stimulates cell growth and development, spurs tissue repair, and ensures the fetus receives nutrition. Without it, the fetus does not receive enough nutrients to develop and grow properly.

What makes insulin-like growth factor 1 especially attractive to Jones’ team is that it stimulates vascularization, or the formation of blood vessels, essential for healthy tissue. In the placenta, that translates to better nutrient transfer.

“One of the things with a growth-restricted placenta is that it doesn’t have as good a vascular tree as a normal placenta does,” Jones said.

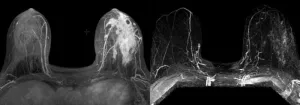

Jones is senior author of a study published in Nature Gene Therapy on Dec. 4 that she said details exciting results. It shows that in guinea pigs, the therapy boosted placental function and delivery of normal-weight offspring. Guinea pigs have biological and physiological conditions during pregnancy that parallel humans.

Surprisingly, the treatment also reduced the mother’s levels of cortisol, the stress hormone. If this holds in humans, the therapy might help lessen a burden many mothers know all too well.

Stress, Jones said, is a normal byproduct of pregnancy. But too much can cause complications thought to contribute to high blood pressure, disruption of a fetus’ brain development, sleep deprivation, and mental health concerns such as depression and anxiety.

Stress can trigger problems for mother and child even many years later, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Common remedies for maternal stress aren’t always practical.

“A mother often has to work right up until delivery, and there’s nothing they can change about that,” said Jones. “They can’t just sit down and put their feet up. And while their doctors tell them to get more exercise, go outside, and not sit at their desks all day, we know that often doesn’t work in the real world. A treatment like ours could be life-changing in some pregnancies.”

The work has been funded for 12 years by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a branch of the National Institutes of Health.

END

Gene therapy fixes major cause of stillbirth, premature birth in guinea pig model

2024-12-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

From one gene switch, many possible outcomes

2024-12-05

Within all complex, multicellular living systems such as plants and humans, there exists a set of genetic elements that can be likened to the blueprints, tools, and specialized personnel at a construction site for an expanding development. Plant biologists like Aman Husbands at the University of Pennsylvania study a family of skilled subcontractors, known as the HD-ZIPIII transcription factors (TFs). These subcontractors are tasked with deciding which blueprints, or genes, to follow as they guide the ...

Visiting Fellows selected for inaugural cohort of the Africa-UBC Oceans and Fisheries Visiting Fellows Program

2024-12-05

The Africa-UBC Oceans and Fisheries Visiting Fellows Program is extremely pleased to announce the selection of its inaugural laureates: Dr. Cynthia A. Adinortey (Ghana) and Dr. Antony Otinga Oteng’o (Kenya).

“We had many excellent applicants from across Sub-Saharan Africa. Ultimately, our Selection Committee selected these two exemplary scholars, and we are most happy with the result,” said Dr. William Cheung, professor and Director of UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF), which administers the Program. “These two exemplary scholars will now have the opportunity to collaborate ...

Innovative immunotherapy shows promise in early clinical trial for breast cancer

2024-12-05

A groundbreaking phase one clinical trial exploring a novel cell-based immunotherapy for breast cancer has been accepted for publication in JAMA Oncology. The technology tested in the trial was co-developed by Gary Koski, Ph.D., professor in Kent State University’s Department of Biological Sciences, and Brian J. Czerniecki, M.D., Ph.D., chair and senior member in the Moffitt Cancer Center’s Department of Breast Oncology. The study focuses on a new treatment approach that aims to harness the body’s immune system to enhance patient responses ...

Whiteness as a fundamental determinant of health in rural America

2024-12-05

WASHINGTON -- White people in rural America have unique factors that drive worse health outcomes than their urban counterparts, prompting a team of public health researchers to label whiteness as a fundamental determinant of health. They say while the health and well-being of racially minoritized populations should continue to be a research priority they urge researchers to consider factors that influence the health of majoritized populations.

In an analytic essay, "Whiteness: A Fundamental Determinant of the Health of Rural White Americans,” published Dec. 5 in the American Journal of Public Health, Caroline Efird, PhD, MPH, ...

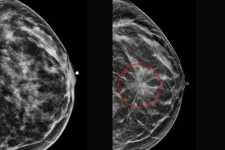

Analyzing multiple mammograms improves breast cancer risk prediction

2024-12-05

A new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis describes an innovative method of analyzing mammograms that significantly improves the accuracy of predicting the risk of breast cancer development over the following five years. Using up to three years of previous mammograms, the new method identified individuals at high risk of developing breast cancer 2.3 times more accurately than the standard method, which is based on questionnaires assessing clinical risk factors alone, such as age, race and family history of breast cancer.

The study is published ...

Molecular zip code draws killer T cells straight to brain tumors

2024-12-05

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak.

Molecular Zip Code Draws Killer T Cells Straight to Brain Tumors

Researchers have found a way to program immune cells to attack glioblastoma and treat the inflammation of multiple sclerosis in mice. The technology will soon be tested in a clinical trial for people with glioblastoma.

UCSF scientists have developed a “molecular GPS” to guide immune cells into the brain and kill tumors without harming healthy tissue.

This living cell therapy can navigate through the body to a specific organ, addressing ...

Engineered immune cells may be able to tame inflammation

2024-12-05

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak.

Engineered Immune Cells May Be Able to Tame Inflammation

Immune cells that are designed to soothe could improve treatment for organ transplants, type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune conditions.

When the immune system overreacts and starts attacking the body, the only option may be to shut the entire system down and risk developing infections or cancer.

But now, scientists at UC San Francisco may have found a more precise way to dial the immune system down.

The technology ...

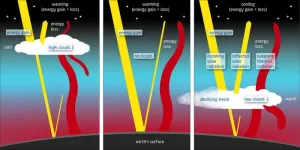

Rapid surge in global warming mainly due to reduced planetary albedo

2024-12-05

Rising sea levels, melting glaciers, heatwaves at sea – 2023 set a number of alarming new records. The global mean temperature also rose to nearly 1.5 degrees above the preindustrial level, another record. Seeking to identify the causes of this sudden rise has proven a challenge for researchers. After all, factoring in the effects of anthropogenic influences like the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, of the weather phenomenon El Niño, and of natural events like volcanic eruptions, can account for a major portion of the warming. But doing so still leaves a gap of roughly 0.2 degrees Celsius, which has never been satisfactorily ...

Single mutation in bovine H5N1 switches viral binding specificity to human receptors

2024-12-05

A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 – a clade of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus that has been increasingly detected among North American livestock herds – can cause the virus to switch affinity from animal-type receptors to human-type receptors, according to a new study. The findings highlight the crucial need for continuous surveillance of emerging H5N1 mutations, as even subtle genetic changes could increase the virus's capacity for human adaptation and transmission, potentially triggering a future influenza pandemic. In 2021, the highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 clade ...

Discovered: the neuroendocrine circuit that dictates when fish are ready to hatch

2024-12-05

Researchers have uncovered a previously unknown yet crucial role for thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Trh) in zebrafish hatching and reveal how this hormone activates a transient neuroendocrine circuit that controls when fish larvae are ready to leave the egg and swim free. For egg-born animals, hatching marks a pivotal shift, transitioning from the sheltered environment of an egg capsule to external conditions. This crucial event is not strictly hardwired into the embryo’s developmental program. Rather, hatching is a regulated ...