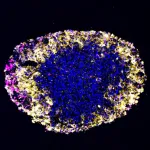

(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA— For the first time, researchers used lab-grown organoids created from tumors of individuals with glioblastoma (GBM) to accurately model a patient’s response to CAR T cell therapy in real time. The organoid’s response to therapy mirrored the response of the actual tumor in the patient’s brain. That is, if the tumor-derived organoid shrunk after treatment, so did the patient’s actual tumor, according to new research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, published today in Cell Stem Cell.

“It’s hard to measure how a patient with GBM responds to treatment because we can’t regularly biopsy the brain, and it can be difficult to discern tumor growth from treatment-related inflammation on MRI imaging,” said Hongjun Song, PhD, the Perelman Professor of Neuroscience and co-senior author of the research. “These organoids reflect what is happening in an individual’s brain with great accuracy, and we hope that they can be used in the future to ‘get to know’ each patient’s distinctly complicated tumor and quickly determine which therapies would be most effective for them for personalized medicine.”

GBM is the most common—and most aggressive—type of cancerous brain tumor in adults. Individuals with GBM usually can expect to live just 12-18 months following their diagnosis. Despite decades of research, there is no known cure for GBM, and approved treatments—such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy—have limited effect in prolonging life expectancy.

A treatment called CAR T cell therapy reprograms a patient’s T cells to find and destroy a specific type of cancer cell in the body. While this therapy is FDA approved to fight several blood cancers, researchers have struggled to engineer cells to successfully seek out and kill solid tumors, like in GBM. Recent research suggests that CAR T cell therapy that targets two brain tumor-associated proteins—rather than one—may be a promising strategy for reducing solid tumor growth in patients with recurrent glioblastoma.

“One of the reasons why GBM is so difficult to treat is because the tumors are incredibly complicated, made up of several different types of cancer cells, immune cells, blood vessels, and other tissue,” said study co-senior author, Guo-li Ming, MD, PhD, the Perelman Professor of Neuroscience and Associate Director of Institute for Regenerative Medicine “By growing the organoid from tiny pieces of a patient’s actual tumor rather than one type of cancer cell, we can mirror how the tumor exists in the patient, as well as the ‘micro-environment’ in which it grows, a major limitation of other models of GBM.”

The first line of treatment for GBM is surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. For this study, researchers created organoids from the tumors of six patients with recurrent glioblastoma participating in a Phase I clinical trial for a dual-target CAR T cell therapy. It can take months to grow enough cancer cells in the lab to test treatments on, but an organoid can be generated in 2-3 weeks, while the individuals recover from surgery and before they can begin CAR T cell therapy.

2-4 weeks following surgery, the CAR T cell therapy was administered to the organoids and the patients at the same time. They found that the treatment response in the organoids correlated with the response of the tumors in the patient. When a patient’s organoid demonstrated cancer cell destruction by T cells, the patient also exhibited a reduced tumor size via MRI imaging and increased presence of CAR-positive T cells in their cerebrospinal fluid, indicating that the therapy met its targets.

A common concern with CAR T cell therapy for GBM is neurotoxicity, which occurs when a toxic substance alters the activity of the nervous system and can disrupt or kill brain cells. The researchers found that there were similar levels of immune cytokines, which indicate toxicity, in both the organoids and the patients’ cerebrospinal fluid. Both levels decreased a week after treatment ended, suggesting that the organoid can also accurately model a patient’s risk of neurotoxicity, and help clinicians determine what size dose of CAR T to use.

“This research shows that our GBM organoids are a powerful and accurate tool for understanding what exactly happens when we treat a brain tumor with CAR T cell therapy,” said study co-senior author, Donald M. O’Rourke, MD, the John Templeton, Jr., MD Professor in Neurosurgery and director of the Glioblastoma Translational Center of Excellence at the Abramson Cancer Center. “Our hope is that not only to bring these to clinic to personalize patient treatment, but also to use the organoids to deepen our understanding of how to outsmart and destroy this complex and deadly cancer.”

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R35NS116843 and R35NS097370), and support from Institute for Regenerative Medicine, and the GBM Translational Center of Excellence in the Abramson Cancer Center.

about cell therapy research at Penn Medicine:

What is CAR T Cell Therapy?

“Dual-Target” cell therapy appears to shrink brain tumors

Engineering the Immune System to Tackle Solid Tumors

For patients interested in clinical trials at Penn Medicine, please call 1-855-216-0098.

###

Penn Medicine is one of the world’s leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, excellence in patient care, and community service. The organization consists of the University of Pennsylvania Health System and Penn’s Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine, founded in 1765 as the nation’s first medical school.

The Perelman School of Medicine is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $550 million awarded in the 2022 fiscal year. Home to a proud history of “firsts” in medicine, Penn Medicine teams have pioneered discoveries and innovations that have shaped modern medicine, including recent breakthroughs such as CAR T cell therapy for cancer and the mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System’s patient care facilities stretch from the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania to the New Jersey shore. These include the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Health, Penn Medicine Princeton Health, and Pennsylvania Hospital—the nation’s first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional facilities and enterprises include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, Penn Medicine at Home, Lancaster Behavioral Health Hospital, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, among others.

Penn Medicine is an $11.1 billion enterprise powered by more than 49,000 talented faculty and staff.

END

Analyzing the sequence of proteins in cohort studies is done by comparing participant data against protein sequences predicted from the human genome.

– Today, the same reference proteins are used for all participants, says associate professor Marc Vaudel at the department of Clinical Science of the University of Bergen – but we are all different! We found that the small genetic changes that make us who we are create a bias: for those who differ from the reference, current informatic methods are blind to parts of their proteins.

To solve this problem, the researchers in Bergen developed new models to build sequences from large genetic ...

(Toronto, December 9, 2024) In a pivotal step toward improving research standards in health care technologies, the Journal of Medical Internet Research has published the RATE-XR guideline. This new tool aims to standardize reporting for early-phase clinical studies involving extended reality (XR) technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality. Developed through a robust, expert-driven process, RATE-XR addresses critical gaps in transparency, safety, and ethical reporting, ensuring XR applications meet the needs of patients and researchers alike.

Led by a multidisciplinary team of international experts, RATE-XR offers a checklist comprising 17 XR-specific ...

A research team led by Prof. Julia Esser-von Bieren from the Center of Allergy and Environment (ZAUM) at Helmholtz Munich and the Technical University of Munich, as well as the University of Lausanne (UNIL) has uncovered a molecular strategy employed by worm parasites (helminths) to evade host immune defenses. This discovery opens new avenues for the development of innovative vaccines and therapies. Published in Science Immunology, the study offers promising solutions for addressing major infectious diseases, allergies, and asthma by leveraging ...

AUSTIN, TX, Dec 9, 2024 – School shooting incidents have doubled in the last three years, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database, which tracks each time a firearm is discharged on school property. Many schools have taken measures to improve safety, including metal detectors, interior door locks, emergency drills, and undercover security. But do students and staff feel any safer?

Researchers at the University of Southern California (USC) conducted a nationwide study of K-12 parents, K-12 teachers, and recently graduated high school students to test their responses ...

SAN ANTONIO — December 9, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute has announced a groundbreaking joint industry project (JIP) to help spur the growth and innovation of fueling technologies and infrastructure for hydrogen-powered heavy-duty vehicles.

SwRI’s H2HD REFUEL (Hydrogen Heavy Duty Refueling Equipment and Facilities Utilization Evaluation Laboratory) JIP aims to strengthen the acceptance of hydrogen fuel use by heavy-duty vehicles to help the mobility industry meet its decarbonization and zero-emissions goals by advancing hydrogen refueling station (HRS) technologies. Over the next four years, SwRI researchers will use hands-on ...

New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope suggest that a new feature in the universe—not a flaw in telescope measurements—may be behind the decadelong mystery of why the universe is expanding faster today than it did in its infancy billions of years ago.

The new data confirms Hubble Space Telescope measurements of distances between nearby stars and galaxies, offering a crucial cross-check to address the mismatch in measurements of the universe’s mysterious expansion. Known as the Hubble tension, the discrepancy remains unexplained even by the best cosmology models.

“The ...

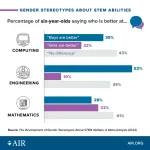

Arlington, Va. – Children as young as age 6 develop gender stereotypes about computer science and engineering, viewing boys as more capable than girls, according to new results from an American Institutes for Research (AIR) study. However, math stereotypes are far less gendered, showing that young children do not view all science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields as the same.

These new findings come from the largest-ever study on children’s gender stereotypes about STEM and verbal abilities, based on data from 145,000 children across 33 nations, synthesizing more than 40 years of ...

Hair loss during chemotherapy can cause enough distress for some women to lose self-confidence, which experts say may discourage them from seeking chemotherapy in the first place.

Oral minoxidil is a commonly prescribed treatment for hair loss. The drug is also the active ingredient in over-the-counter Rogaine. The prescription treatment is known, however, to dilate blood vessels, and experts worry that this could increase the heart-related side effects of chemotherapy and lead to chest pain, shortness of breath, or fluid buildup.

Now, a study in women with breast cancer suggests that low oral doses of minoxidil, taken during ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio – If you feel terrible about giving a late gift to a friend for Christmas or their birthday, a new study has good news for you.

Researchers found that recipients aren’t nearly as upset about getting a late gift as givers assume they will be.

“Go ahead and send that late gift, because it doesn’t seem to bother most people as much as givers fear,” said Cory Haltman, lead author of the study and doctoral student in marketing at The Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business.

In a series of six studies, Haltman and his colleagues explored the mismatch between givers’ ...

We tie our shoes, we put on neckties, we wrestle with power cords. Yet despite deep familiarity with knots, most people cannot tell a weak knot from a strong one by looking at them, new Johns Hopkins University research finds.

Researchers showed people pictures of two knots and asked them to point to the strongest one. They couldn’t.

They showed people videos of each knot, where the knots spin slowly so they could get a good long look. They still failed.

People couldn’t even manage it ...