(Press-News.org) A new approach to treat rosacea and other inflammatory skin conditions could be on the horizon, according to a University of Pittsburgh study published today in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that a compound called SYM2081 inhibited inflammation-driving mast cells in mouse models and human skin samples, paving the way for new topical treatments to prevent itching, hives and other symptoms of skin conditions driven by mast cells.

“I’m really excited about the clinical possibilities of this research,” said senior author Daniel Kaplan, M.D., Ph.D., professor of dermatology and immunology at Pitt. “Currently, there aren’t a lot of good therapies that target mast cells, so we think that our approach could potentially have huge benefits in many skin conditions, including rosacea, eczema, urticaria and mastocytosis.”

Mast cells are filled with tiny packages, or granules, each brimming with histamine and other compounds that act as signals or activators of inflammatory pathways. When mast cells are activated, the packages spill open, releasing compounds that trigger a suite of immune responses. This process, known as degranulation, is essential for protection against threats such as bee venom, snake bites and pathogenic bacteria, but erroneous activation of mast cells also triggers allergic reactions, including swelling, hives, itching and, in severe cases, anaphylaxis.

In a previous Cell paper, Kaplan and his team found that neurons in the skin release a neurotransmitter called glutamate that suppresses mast cells. When they deleted these neurons or inhibited the receptor that recognizes glutamate, mast cells became hyperactive, leading to more inflammation.

“This finding led us to wonder if doing the opposite would have a beneficial effect,” said Kaplan. “If we activate the glutamate receptor, maybe we can suppress mast cell activity and inflammation.”

To test this hypothesis, lead author Youran Zhang, a medical student at Tsinghua University who did this research as a visiting scholar in Kaplan’s lab, and Tina Sumpter, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Pitt Department of Dermatology, looked at a compound called SYM2081, or 4-methylglutamate, that activates a glutamate receptor called GluK2 found almost exclusively on mast cells.

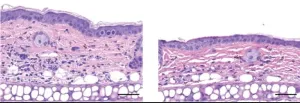

Sure enough, they found that SYM2081 effectively suppressed mast cell degranulation and proliferation in both mice and human skin samples. And when the mice received a topical cream containing SYM2081 before the induction of rosacea- or eczema-like symptoms, skin inflammation and other symptoms of disease were much milder.

According to Kaplan, these findings suggest that suppressing mast cells with a daily cream containing a GluK2-activating compound could be a promising way to prevent rosacea and other inflammatory skin conditions.

Rosacea is a chronic skin condition that may cause acne-like pimples, broken blood vessels, skin thickening and facial flushing.

“Although there are excellent therapies available for different types of rosacea, many are antibiotic-based and they only target some of the symptoms,” said Kaplan. “There are no good therapies for flushing, so this is a significant unmet need. Our study suggests that suppressing mast cells by activating GluK2 could reduce the flushing associated with rosacea.”

Now that the researchers have demonstrated proof-of-concept of their approach, they hope to engineer new GluK2-activating compounds that could eventually be tested in clinical trials. Through the Pitt Office of Innovation and Entrepreneurship’s Innovation Institute, they have also applied for a patent for the use of SYM2081 to suppress mast cell function.

Other authors on the study were Swapnil Keshari, Kazuo Kurihara, M.D., Ph.D., James Liu, Lindsay M. McKendrick, Chien-Sin Chen, Ph.D., Louis D. Falo Jr., M.D., Ph.D., and Jishnu Das, Ph.D., all of Pitt; and Yufan Yang, of Pitt and Tsinghua University.

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health (NIH; R01AR071720, R01 AR077341, R01AR079233, R01AR074285, DP2AI164325, U01EY034711 and T32AI089443) and the Pitt Center for Research Computing, which is supported by the NIH (S10OD028483).

END

Feeling itchy? Study suggests novel way to treat inflammatory skin conditions

2024-12-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Caltech creates minuscule robots for targeted drug delivery

2024-12-11

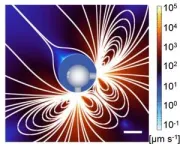

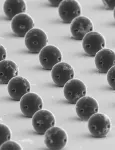

In the future, delivering therapeutic drugs exactly where they are needed within the body could be the task of miniature robots. Not little metal humanoid or even bio-mimicking robots; think instead of tiny bubble-like spheres.

Such robots would have a long and challenging list of requirements. For example, they would need to survive in bodily fluids, such as stomach acids, and be controllable, so they could be directed precisely to targeted sites. They also must release their medical cargo only when they reach their target, and then be absorbable by the body without causing harm.

Now, ...

Noninvasive imaging method can penetrate deeper into living tissue

2024-12-11

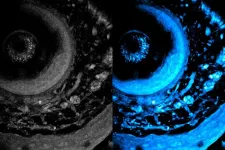

Metabolic imaging is a noninvasive method that enables clinicians and scientists to study living cells using laser light, which can help them assess disease progression and treatment responses.

But light scatters when it shines into biological tissue, limiting how deep it can penetrate and hampering the resolution of captured images.

Now, MIT researchers have developed a new technique that more than doubles the usual depth limit of metabolic imaging. Their method also boosts imaging speeds, yielding richer and more detailed images.

This new technique does not require tissue to be ...

Researchers discover zip code that allows proteins to hitch a ride around the body

2024-12-11

Researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa have discovered an 18-digit code that allows proteins to attach themselves to exosomes - tiny pinched-off pieces of cells that travel around the body and deliver biochemical signals. The discovery, published in Science Advances, has major implications for the burgeoning field of exosome therapy, which seeks to harness exosomes to deliver drugs for various diseases.

“Proteins are the body’s own home-made drugs, but they don’t necessarily travel well around the body,” said Dr. Michael Rudnicki, senior ...

The distinct nerve wiring of human memory

2024-12-11

The black box of the human brain is starting to open. Although animal models are instrumental in shaping our understanding of the mammalian brain, scarce human data is uncovering important specificities. In a paper published in Cell, a team led by the Jonas group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) and neurosurgeons from the Medical University of Vienna shed light on the human hippocampal CA3 region, central for memory storage.

Many of us have relished those stolen moments with a grandparent by the fireplace, our hearts racing to the intrigues of their stories from good old times, recounted with vivid imagery ...

Researchers discover new third class of magnetism that could transform digital devices

2024-12-11

A new class of magnetism called altermagnetism has been imaged for the first time in a new study. The findings could lead to the development of new magnetic memory devices with the potential to increase operation speeds of up to a thousand times.

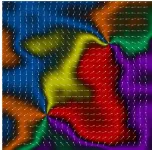

Altermagnetism is a distinct form of magnetic order where the tiny constituent magnetic building blocks align antiparallel to their neighbours but the structure hosting each one is rotated compared to its neighbours.

Scientists from the University of Nottingham’s School of Physics and Astonomy have shown that this new third class ...

Personalized blood count could lead to early intervention for common diseases

2024-12-11

A complete blood count (CBC) screening is a routine exam requested by most physicians for healthy adults. This clinical test is a valuable tool for assessing a patient’s overall health from one blood sample. Currently, the results of CBC tests are analyzed using a one-size-fits-all reference interval, but a new study led by researchers from Mass General Brigham suggests that this approach can lead to overlooked deviations in health. In a retrospective analysis, researchers show that these reference intervals, or setpoints, are unique to each patient. The study revealed that one healthy ...

Innovative tissue engineering: Boston University's ESCAPE method explained

2024-12-11

When it comes to the human body, form and function work together. The shape and structure of our hands enable us to hold and manipulate things. Tiny air sacs in our lungs called alveoli allow for air exchange and help us breath in and out. And tree-like blood vessels branch throughout our body, delivering oxygen from our head to our toes. The organization of these natural structures holds the key to our health and the way we function. Better understanding and replicating their designs could help us unlock biological insights for more effective drug-testing, and the development of new therapeutics and organ replacements. Yet, biologically engineering tissue ...

Global healthspan-lifespan gaps among 183 WHO member states

2024-12-11

About The Study: This study identifies growing healthspan (years lived in good health)-lifespan gaps around the globe, threatening healthy longevity across worldwide populations. Women globally exhibited a larger healthspan-lifespan gap than men.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Andre Terzic, MD, PhD, email terzic.andre@mayo.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.50241)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article ...

Stanford scientists transform ubiquitous skin bacterium into a topical vaccine

2024-12-11

Imagine a world in which a vaccine is a cream you rub onto your skin instead of a needle a health care worker pushes into your one of your muscles. Even better, it’s entirely pain-free and not followed by fever, swelling, redness or a sore arm. No standing in a long line to get it. Plus, it’s cheap.

Thanks to Stanford University researchers’ domestication of a bacterial species that hangs out on the skin of close to everyone on Earth, that vision could become a reality.

“We all hate needles — everybody does,” said Michael Fischbach, PhD, the Liu (Liao) Family Professor and a professor of bioengineering. “I haven’t found a single person ...

Biological diversity is not just the result of genes

2024-12-11

How can we explain the morphological diversity of living organisms? Although genetics is the answer that typically springs to mind, it is not the only explanation. By combining observations of embryonic development, advanced microscopy, and cutting-edge computer modelling, a multi-disciplinary team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) demonstrate that the crocodile head scales emerge from the mechanics of growing tissues, rather than molecular genetics. The diversity of these head scales observed in different crocodilian species therefore arises from the evolution of mechanical parameters, such as the growth ...