(Press-News.org) By Beth Miller

In mechanobiology, cells’ forces have been considered fundamental to their enhanced function, including fast migration. But a group of researchers in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis has found that cells can generate and use lower force yet move faster than cells generating and using high forces, turning the age-old assumption of force on its head.

The laboratory of Amit Pathak, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science, found that groups of cells moved faster with lower force when adhered to soft surfaces with aligned collagen fibers. Cells have been thought to continually generate forces as they must overcome friction and drag of their environment to move. However, this conventional need for forces can be reduced in favorable environmental conditions, such as aligned fibers. Their results, published in PLOS Computational Biology Jan. 9, are the first to show this activity in collective cell migration.

Pathak and members of his lab have tracked the movement of human mammary epithelial cells for years, determining that cells move faster on a hard, stiff surface than on a soft surface, where they get stuck. Their research has implications in cancer metastasis and wound healing.

In the new research, they found that cells migrated more than 50% faster on aligned collagen fibers than on random fibers. In addition, they found that cells use aligned fibers as directional cues to guide their migration toward expanding their group.

“We wondered if you apply a force, and there's no friction, can the cells keep going fast without generating more force?” Pathak said. “We realized it's probably dependent on the environment. We thought they would be faster on aligned fibers, like railroad tracks, but what was surprising was that they were actually generating lower forces and still going faster.”

Amrit Bagchi, who earned a doctorate in mechanical engineering from McKelvey Engineering in 2022 in Pathak’s lab and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Engineering MechanoBiology at the University of Pennsylvania, went to great lengths to set up the research. Bagchi created a soft hydrogel in the laboratory of Marcus Foston, associate professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering, over many months during the COVID-19 pandemic, then aligned the fibers using a special magnet at the School of Medicine before putting the cells on it to track their movement.

Bagchi developed a multi-layered motor-clutch model in which the force-generating mechanisms in the cells act as the motor, and the clutch provides the traction for the cells. Bagchi expertly converted the model for the collective cells using three layers — one for cells, one for the collagen fibers and one for the custom gel underneath — which all communicated with each other.

“Although the experimental results initially surprised us, they provided the impetus to develop a theoretical model to explain the physics behind this counterintuitive behavior,” Bagchi said. “Over time, we came to understand that cells use aligned fibers as a proxy for experiencing frictional forces in a way that differs significantly from the random fiber condition. Our model's concept of matrix mechanosensing and transmission also predicts other well-known collective migration behaviors, such as haptotaxis and durotaxis, offering a unified framework for scientists to explore and potentially extend to other interesting cell migration phenotypes.”

###

Bagchi A, Sarker B, Zhang J, Foston M, Pathak A. Fast yet force-effective mode of supracellular collective cell migration due to extracellular force transmission. PLOS Computational Biology, Jan. 9, 2025, DOI: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012664.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R35GM12876) and the National Science Foundation (CMMI:154857 and CMMI 2209684).

Codes used for generating simulations can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13984567

END

May the force not be with you: Cell migration doesn't only rely on generating force

2025-01-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NTU Singapore-led discovery poised to help detect dark matter and pave the way to unravel the universe’s secrets

2025-01-09

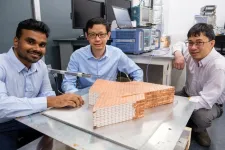

Researchers led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have developed a breakthrough technique that could lay the foundations for detecting the universe’s “dark matter” and bring scientists closer than before to uncovering the secrets of the cosmos.

The things we can see on Earth and in space – visible matter like rocks and stars – make up only a small portion of the universe, as scientists believe that 85 per cent of matter in the cosmos comprises invisible dark matter. This mysterious substance ...

Researchers use lab data to rewrite equation for deformation, flow of watery glacier ice

2025-01-09

AMES, Iowa – Neal Iverson started with two lessons in ice physics when asked to describe a research paper about glacier ice flow that has just been published by the journal Science.

First, said the distinguished professor emeritus of Iowa State University’s Department of the Earth, Atmosphere, and Climate, there are different types of ice within glaciers. Parts of glaciers are at their pressure-melting temperature and are soft and watery.

That temperate ice is like an ice cube left on a kitchen counter, with meltwater ...

Did prehistoric kangaroos run out of food?

2025-01-09

Prehistoric kangaroos in southern Australia had a more general diet than previously assumed, giving rise to new ideas about their survival and resilience to climate change, and the final extinction of the megafauna, a new study has found.

The new research, a collaboration between palaeontologists from Flinders University and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), used advanced dental analysis techniques to study microscopic wear patterns on fossilised kangaroo teeth.

The findings, published in Science, suggest that many species of kangaroos were generalists, able to adapt to diverse diets in response to environmental changes.

More ...

HKU Engineering Professor Kaibin Huang named Fellow of the US National Academy of Inventors

2025-01-09

The US National Academy of Inventors (NAI) announced the 2024 Class of Fellows on December 10, 2024. Professor Kaibin Huang of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EEE), Faculty of Engineering, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), was elected a 2024 Fellow in recognition of his inventions and contributions in tackling real-world issues.

Election to NAI Fellow status is the highest professional distinction accorded to academic inventors who have demonstrated a prolific spirit of innovation in creating or facilitating outstanding inventions that have made a tangible impact on ...

HKU Faculty of Arts Professor Charles Schencking elected as Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities

2025-01-09

Professor Charles Schencking, Professor of History of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), has been elected as a Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities (the Academy).

The Australian Academy of the Humanities was established in 1969 by Royal Charter to advance knowledge of, and the pursuit of excellence in, the Humanities. It is an independent, not-for-profit organisation with a Fellowship of over 730 distinguished humanities researchers, leaders, and practitioners ...

Rise in post-birth blood pressure in Asian, Black, and Hispanic women linked to microaggressions

2025-01-09

A study of more than 400 Asian, Black and Hispanic women who had recently given birth found that racism through microaggressions may be linked to higher blood pressure during the period after their baby was born, according to a new study by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. More than one-third of the mothers reported experiencing at least one microaggression related to being a woman of color during or after their pregnancy. The research conducted with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania ...

Weight changes and heart failure risk after breast cancer development

2025-01-09

About The Study: In this nationwide cohort study in the Republic of Korea, postdiagnosis weight gain was associated with an increased risk of heart failure after breast cancer development, with risk escalating alongside greater weight gain. The findings underscore the importance of effective weight intervention in the oncological care of patients with breast cancer, particularly within the first few years after diagnosis, to protect cardiovascular health.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Dong Wook Shin, MD, DrPH, MBA, email dwshin@skku.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

Changes in patient care experience after private equity acquisition of US hospitals

2025-01-09

About The Study: This study found that patient care experience worsened after private equity acquisition of hospitals. These findings raise concern about the implications of private equity acquisitions on patient care experience at U.S. hospitals.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Rishi K. Wadhera, MD, MPP, MPhil, email rwadhera@bidmc.harvard.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.23450)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women in the US

2025-01-09

About The Study: The results of this study suggest that addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women requires a multifaceted approach that acknowledges historical traumas, provides clear and transparent safety information, and avoids coercive vaccine promotion strategies. These findings emphasize the need for health care practitioners and public health officials to prioritize trust-building, engage community leaders, and tailor interventions to address the unique concerns of Black women to improve vaccine confidence and uptake.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Brittany C. Slatton, PhD, email brittany.slatton@tsu.edu.

To access the ...

An earful of gill: USC Stem Cell study points to the evolutionary origin of the mammalian outer ear

2025-01-09

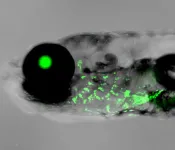

The outer ear is unique to mammals, but its evolutionary origin has remained a mystery. According to a new study published in Nature from the USC Stem Cell lab of Gage Crump, this intricate coil of cartilage has a surprisingly ancient origin in the gills of fishes and marine invertebrates.

“When we started the project, the evolutionary origin of the outer ear was a complete black box,” said corresponding author Crump, professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “We had been studying the development and regeneration of the jawbones of fishes, and an inspiration for us was Stephen ...