(Press-News.org) AMES, Iowa – Neal Iverson started with two lessons in ice physics when asked to describe a research paper about glacier ice flow that has just been published by the journal Science.

First, said the distinguished professor emeritus of Iowa State University’s Department of the Earth, Atmosphere, and Climate, there are different types of ice within glaciers. Parts of glaciers are at their pressure-melting temperature and are soft and watery.

That temperate ice is like an ice cube left on a kitchen counter, with meltwater pooling between the ice and the countertop, he said. Temperate ice has been difficult to study and characterize.

Second, other parts of glaciers have cold, hard ice, like an ice cube still in the freezer. This is the kind of ice that has typically been studied and used as the basis of glacier flow models and forecasts.

The new research paper, “Linear-viscous flow of temperate ice,” deals with the former, said Iverson, a paper co-author and project supervisor. (See sidebar for a list of all co-authors.)

The paper describes lab experiments and the resulting data that suggest a standard value within the “empirical foundation of glacier flow modeling” – an equation known as Glen’s flow law, named after the late John W. Glen, a British ice physicist – should be changed for temperate ice.

The new value when used in the flow law “will tend to predict increases in flow velocity that are much smaller in response to increased stresses caused by ice sheet shrinkage as the climate warms,” Iverson said. That would mean models will show less glacier flow into oceans and project less sea-level rise.

An acute need to account for warm glacier ice

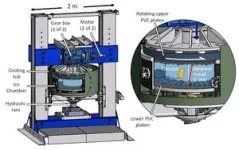

Open the walk-in freezer in Iverson’s campus lab and you’re looking at a 9-foot-tall ring-shear device that’s been simulating glacial forces and movement since 2009. It was built with a $530,000 grant from the National Science Foundation. The current study was also supported by NSF grants.

At the center of the device is a ring of ice about 3 feet across and 7 inches thick. Below the ring is a hydraulic press that can put as much as 100 tons of force on the ice and simulate the weight of a glacier 800 feet thick. The ice ring is surrounded by a tub of circulating fluid that regulates the ice temperature to the nearest hundredth of a degree. Electric motors attached to a plate with grippers above the ice ring can rotate the ice at speeds of 1 to 10,000 feet per year.

For this project, researchers modified the device by adding another gripper to the bottom of the ice ring so that rotation of the upper gripper shears the underlying ice.

Collin Schohn, a former master’s degree student at Iowa State who’s now a geologist with the BBJ Group based in Chicago and is the first author of the group’s latest research paper, ran a series of six experiments using the modified device, each experiment lasting about six weeks. The experiments included measurements of the ice’s liquid water content, something that hadn’t been done in these kinds of experiments since the 1970s.

“These experiments involved deforming the ice at its melting temperatures and at various stresses,” Schohn said.

Iverson likened the experiments to grabbing a bagel at the top and the bottom, then twisting the two halves to smear the cream cheese in the middle.

The experimental data showed that ice deformed at a speed that was linearly proportional to the stress, Iverson said. Traditional thinking would have researchers expecting ice to soften with increasing stress, so increments in stress would cause increasingly large increments in speed.

Why does all this matter?

Ice is temperate near the bottoms and edges of the fastest flowing parts of ice sheets and in fast-flowing mountain glaciers, both of which shed ice into oceans and influence sea level. “The need to model and forecast accurately the flow of warm glacier ice is, therefore, acute,” the authors wrote.

Resetting n to 1.0

Glen’s flow law is written as: ε ̇ = Aτn.

The equation relates the stress on ice, τ, to its rate of deformation, ε ̇, where A is a constant for a particular ice temperature. Results of the new experiments show that the value of the stress exponent, n, is 1.0 rather than the usually assigned value of 3 or 4.

The authors wrote, “For generations, based on Glen’s original experiments and many subsequent experiments mostly on cold ice (-2 degrees C and colder), the value of the stress exponent n in models has been taken to be 3.0.” (They also wrote that other studies of the “cold ice of ice sheets” have placed n higher yet, at 4.0.)

That was, in part, “because experiments with ice at the pressure melting temperature are a challenge,” said Lucas Zoet, a paper co-author, a former postdoctoral research associate at Iowa State and the Dean L. Morgridge Associate Professor of geoscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Zoet, a co-supervisor of the project, has built a slightly smaller version of the ring-shear device with transparent walls for his laboratory.

But data from the large-scale, shear-deformation experiments in Iverson’s lab raised questions about the assigned value for n. Temperate ice is linear-viscous (n = 1.0) “over common ranges of liquid water content and stress expected near glacier beds and in ice stream margins,” the authors wrote.

They proposed that the cause is melting and refreezing along the boundaries of individual, millimeter-to-centimeter scale grains of ice, which should occur at rates linearly proportional to the stress.

These new data allow modelers “to base their ice sheet models on physical relationships demonstrated in the laboratory,” Zoet said. “Improving that understanding improves the accuracy of predictions.”

It took some perseverance to get the data supporting the new value of n.

“We had been batting this project around for years,” Schohn said. “It was really hard to get this to work.”

In the end, Iverson said, “considering all the failures and development, this was about a 10-year process.”

A long process, the researchers said, that’s essential for more accurate models of temperate glacier ice and better predictions of glacier flow and sea-level rise.

– 30 –

END

Researchers use lab data to rewrite equation for deformation, flow of watery glacier ice

2025-01-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Did prehistoric kangaroos run out of food?

2025-01-09

Prehistoric kangaroos in southern Australia had a more general diet than previously assumed, giving rise to new ideas about their survival and resilience to climate change, and the final extinction of the megafauna, a new study has found.

The new research, a collaboration between palaeontologists from Flinders University and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), used advanced dental analysis techniques to study microscopic wear patterns on fossilised kangaroo teeth.

The findings, published in Science, suggest that many species of kangaroos were generalists, able to adapt to diverse diets in response to environmental changes.

More ...

HKU Engineering Professor Kaibin Huang named Fellow of the US National Academy of Inventors

2025-01-09

The US National Academy of Inventors (NAI) announced the 2024 Class of Fellows on December 10, 2024. Professor Kaibin Huang of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EEE), Faculty of Engineering, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), was elected a 2024 Fellow in recognition of his inventions and contributions in tackling real-world issues.

Election to NAI Fellow status is the highest professional distinction accorded to academic inventors who have demonstrated a prolific spirit of innovation in creating or facilitating outstanding inventions that have made a tangible impact on ...

HKU Faculty of Arts Professor Charles Schencking elected as Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities

2025-01-09

Professor Charles Schencking, Professor of History of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), has been elected as a Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities (the Academy).

The Australian Academy of the Humanities was established in 1969 by Royal Charter to advance knowledge of, and the pursuit of excellence in, the Humanities. It is an independent, not-for-profit organisation with a Fellowship of over 730 distinguished humanities researchers, leaders, and practitioners ...

Rise in post-birth blood pressure in Asian, Black, and Hispanic women linked to microaggressions

2025-01-09

A study of more than 400 Asian, Black and Hispanic women who had recently given birth found that racism through microaggressions may be linked to higher blood pressure during the period after their baby was born, according to a new study by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. More than one-third of the mothers reported experiencing at least one microaggression related to being a woman of color during or after their pregnancy. The research conducted with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania ...

Weight changes and heart failure risk after breast cancer development

2025-01-09

About The Study: In this nationwide cohort study in the Republic of Korea, postdiagnosis weight gain was associated with an increased risk of heart failure after breast cancer development, with risk escalating alongside greater weight gain. The findings underscore the importance of effective weight intervention in the oncological care of patients with breast cancer, particularly within the first few years after diagnosis, to protect cardiovascular health.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Dong Wook Shin, MD, DrPH, MBA, email dwshin@skku.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

Changes in patient care experience after private equity acquisition of US hospitals

2025-01-09

About The Study: This study found that patient care experience worsened after private equity acquisition of hospitals. These findings raise concern about the implications of private equity acquisitions on patient care experience at U.S. hospitals.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Rishi K. Wadhera, MD, MPP, MPhil, email rwadhera@bidmc.harvard.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.23450)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women in the US

2025-01-09

About The Study: The results of this study suggest that addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women requires a multifaceted approach that acknowledges historical traumas, provides clear and transparent safety information, and avoids coercive vaccine promotion strategies. These findings emphasize the need for health care practitioners and public health officials to prioritize trust-building, engage community leaders, and tailor interventions to address the unique concerns of Black women to improve vaccine confidence and uptake.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Brittany C. Slatton, PhD, email brittany.slatton@tsu.edu.

To access the ...

An earful of gill: USC Stem Cell study points to the evolutionary origin of the mammalian outer ear

2025-01-09

The outer ear is unique to mammals, but its evolutionary origin has remained a mystery. According to a new study published in Nature from the USC Stem Cell lab of Gage Crump, this intricate coil of cartilage has a surprisingly ancient origin in the gills of fishes and marine invertebrates.

“When we started the project, the evolutionary origin of the outer ear was a complete black box,” said corresponding author Crump, professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “We had been studying the development and regeneration of the jawbones of fishes, and an inspiration for us was Stephen ...

A Sustainable Development Goal for space?

2025-01-09

Scientists have called for the designation of a new United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) with the aim to conserve and sustainably use Earth's orbit, and prevent the accumulation of space junk.

There are currently 17 SDGs, adopted by UN members in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet for future generations, and ensure all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

But with growing numbers of satellites and other objects now orbiting our planet, there is growing concern that without some form of global consensus ...

The Balbiani body: Cracking the secret of embryonic beginnings

2025-01-09

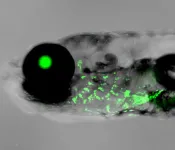

Researchers have uncovered how egg cells prepare for the creation of life. Their work reveals the secrets of the Balbiani body, a remarkable structure that organizes essential molecules to guide early embryonic development. Using zebrafish models and cutting-edge imaging, the team discovered how this structure transforms from liquid droplets into a stable core, laying the groundwork for life itself. This discovery sheds light on the extraordinary precision of nature’s reproductive process.

A new study led by Prof. Yaniv Elkouby and his team, including first co-authors Swastik Kar and Rachael Deis, from the Faculty of Medicine at the Hebrew University ...