From drops to data: Advancing global precipitation estimates with the LETKF algorithm

Researchers propose a new data assimilation algorithm to improve precipitation predictions worldwide

2025-01-15

(Press-News.org)

With the increase in climate change, global precipitation estimates have become a necessity for predicting water-related disasters like floods and droughts, as well as for managing water resources. The most accurate data that can be used for these predictions are ground rain gauge observations, but it is often challenging due to limited locations and sparse rain gauge data. To solve this problem, Assistant Professor Yuka Muto from the Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Japan, and Professor Shunji Kotsuki of the Institute for Advanced Academic Research, Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, as well as the Research Institute of Disaster Medicine of Chiba University, Japan, have created a state-of-the-art method using the Local Ensemble Transform Kalman Filter (LETKF) technique. This study was published in Volume 28, Issue 24 of Hydrology and Earth System Sciences on December 17, 2024.

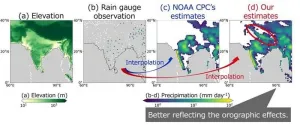

LETKF is a sophisticated data assimilation algorithm that makes global precipitation fields more accurate and is used in meteorology, oceanography, and environmental science. It combines real-world observations with computer model simulations to provide accurate, real-time predictions of complex systems. When combined with different inputs, like sensors, satellites, and ground stations, it can provide more precise predictions, minimizing errors. In this study, Dr. Muto and Professor Kotsuki used the LETKF to enhance the ground data estimates through reanalysis. “We aimed to enhance the global precipitation estimates by integrating reliable ground rain gauge observations with dynamically consistent data from reanalysis precipitation,” explains Dr. Muto when talking to us about the rationale behind this study. Adding further, she says, “We observed that the LETKF algorithm not only improves the accuracy of the precipitation estimates, but it also offers computational efficiency, making it a reliable solution for large-scale applications.”

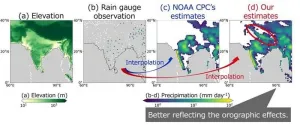

To begin with, the team required two sets of inputs: the actual rain gauge observation data and the reanalysis data. For this, they utilized rain gauge observations acquired from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Prediction Center (NOAA CPC). They further incorporated the reanalysis precipitation data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5), which is a fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis dataset produced by the ERA5 using satellite inputs and numerical weather prediction models. By using a 20-year climatological dataset from the ERA5 data (for 10 years before and 10 years after a given date), the LETKF algorithm constructed a “first guess” for the precipitation field and its error covariance. Further, the rain gauge observations from NOAA CPC were integrated into these first-guess ERA5-based precipitation fields by using the LETKF. The model enabled precise interpolation, even for regions that have sparse observational coverage.

Explaining the efficiency of this method, Professor Kotsuki adds, “Our estimates showed better agreement with independent rain gauge observations and were more reliable even in mountainous or rain-gauge-sparse regions when compared to the existing NOAA CPC product.” The model showed significant improvements in capturing the precipitation patterns in areas including the Himalayas, the Andes, and the central region of Africa. This reliability could hold a high potential in addressing natural disasters and resource allocations.

The proposed methodology is more reliable than conventional techniques due to its ability to construct a physically consistent first-guess estimate by using reanalysis data. In this, the model preserves the critical variations in precipitation patterns while reducing the smoothing effects that are often observed in existing models. This dynamic consistency is especially beneficial for complex terrains, like mountains, where conventional methods struggle.

Reflecting on the long-term implications of the study, Dr. Muto adds, “We believe that accurate precipitation estimates can transform how we prepare for and respond to disasters. By reducing uncertainty, we can mitigate economic losses, support sustainable water management, and prevent the stagnation of economic activities caused by extreme weather events.”

In summary, this study holds the potential to drive international collaborations and also innovations in climate science to ensure that global water resources are managed well to meet the challenges of the changing climate.

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2025-01-15

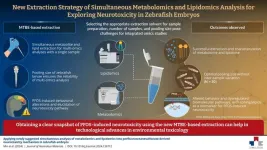

The term “omics” refers to the study of entirety of molecular mechanisms that happen inside an organism. With the advent of omics technologies like transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics, our understanding of molecular pathways of toxic environmental pollutants has deepened. But most environmental toxicology studies are still dependent on a single-omics analyses, leading to gaps in our understanding of integrated toxicity pathways of pollutants. Researchers from all over the world have ...

2025-01-15

The Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) has reached its enrollment goal of 108,508 women, as announced today by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (ECOG-ACRIN). The study, funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), one of the National Institutes of Health, will now proceed with the completion of regularly scheduled mammograms and follow-up on all participants through 2027. Key in this follow-up is the collection of biospecimens and data that will help researchers learn how to personalize breast cancer screening for women.

Participants in TMIST were randomly ...

2025-01-15

WASHINGTON - Women who were cared for by the MedStar Health D.C. Safe Babies Safe Moms program (SBSM) have better outcomes in pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum, according to a study published today in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. Additionally, the study showed that Black patients cared for by SBSM were also less likely to have low or very low birthweight babies or preterm birth than Black or White patients who received prenatal care elsewhere.

Compared to patients who received prenatal care elsewhere, patients cared for under Safe ...

2025-01-15

Octopus arms move with incredible dexterity, bending, twisting, and curling with nearly infinite degrees of freedom. New research from the University of Chicago revealed that the nervous system circuitry that controls arm movement in octopuses is segmented, giving these extraordinary creatures precise control across all eight arms and hundreds of suckers to explore their environment, grasp objects, and capture prey.

“If you're going to have a nervous system that's controlling such dynamic movement, that's a good way to set it up,” said Clifton Ragsdale, PhD, Professor of Neurobiology at UChicago and senior author ...

2025-01-15

The three-dimensional shape of a protein can be used to resolve deep, ancient evolutionary relationships in the tree of life, according to a study in Nature Communications.

It is the first time researchers use data from protein shapes and combine it with data from genomic sequences to improve the reliability of evolutionary trees, a critical resource used by the scientific community for understanding the history of life, monitor the spread of pathogens or create new treatments for disease.

Crucially, the approach works even with the ...

2025-01-15

PHILADELPHIA, PA (January 15, 2025) - Can memory influence what and how much we eat? A groundbreaking Monell Chemical Senses Center study, which links food memory to overeating, answered that question with a resounding “Yes.” Led by Monell Associate Member Guillaume de Lartigue, PhD, the research team identified, for the first time, the brain’s food-specific memory system and its direct role in overeating and diet-induced obesity.

Published in Nature Metabolism, they describe a specific population of neurons in the mouse brain that encode memories for sugar and fat, profoundly impacting food intake and body ...

2025-01-15

Indigenous students identified inadequate funding as a major barrier to completing post-secondary education according to a new study published in AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples.

The study surveyed Indigenous university students at Algoma University. The students, who identified as either First Nations or Métis, reported that they required multiple sources of funding, including government student loans and personal savings, to afford their post-secondary education. About two-thirds (69%) of students received funding for their education from First Nations sources, including funding from federal programs for Indigenous students.

“This ...

2025-01-15

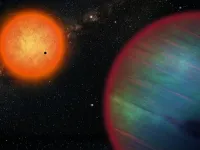

Hot Jupiters are giant planets initially known to orbit alone close to their star. During their migration towards their star, these planets were thought to accrete or eject any other planets present. However, this paradigm has been overturned by recent observations, and the final blow could come from a new study led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE). A team including the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, the Universities of Bern (UNIBE) and Zurich (UZH) and several foreign universities has just announced the existence of a planetary system, WASP-132, ...

2025-01-15

University of Birmingham venture Dexter has demonstrated the power of its Dexter software platform in a study showing that people whose childhoods featured abuse, neglect or domestic abuse carry a significantly increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis in later life.

The starting point for the recently published study was a database of over 16 million Electronic Health Records, from which the Dexter software defined a cohort, one arm that was exposed to childhood maltreatment, and one arm that was not.

The software then checked the records over a 26-year period ...

2025-01-15

The discovery of two new planets beyond our solar system by a team of astronomers from The University of Warwick and the University of Geneva (UNIGE), is challenging scientific understanding of how planetary systems form.

The existence of these two exoplanets - an inner super-Earth and an outer icy giant planet - within the WASP-132 system is overturning accepted paradigms of how ‘hot Jupiter’ planetary systems form and evolve.

Hot Jupiters are planets with masses similar to those of Jupiter, but which orbit closer to their star than Mercury orbits the Sun. There is not enough gas and dust for these giant planets to form ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] From drops to data: Advancing global precipitation estimates with the LETKF algorithm

Researchers propose a new data assimilation algorithm to improve precipitation predictions worldwide