(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA — With a more efficient method for artificial pollination, farmers in the future could grow fruits and vegetables inside multilevel warehouses, boosting yields while mitigating some of agriculture’s harmful impacts on the environment.

To help make this idea a reality, MIT researchers are developing robotic insects that could someday swarm out of mechanical hives to rapidly perform precise pollination. However, even the best bug-sized robots are no match for natural pollinators like bees when it comes to endurance, speed, and maneuverability.

Now, inspired by the anatomy of these natural pollinators, the researchers have overhauled their design to produce tiny, aerial robots that are far more agile and durable than prior versions.

The new bots can hover for about 1,000 seconds, which is more than 100 times longer than previously demonstrated. The robotic insect, which weighs less than a paperclip, can fly significantly faster than similar bots while completing acrobatic maneuvers like double aerial flips.

The revamped robot is designed to boost flight precision and agility while minimizing the mechanical stress on its artificial wing flexures, which enables faster maneuvers, increased endurance, and a longer lifespan.

The new design also has enough free space that the robot could carry tiny batteries or sensors, which could enable it to fly on its own outside the lab.

“The amount of flight we demonstrated in this paper is probably longer than the entire amount of flight our field has been able to accumulate with these robotic insects. With the improved lifespan and precision of this robot, we are getting closer to some very exciting applications, like assisted pollination,” says Kevin Chen, an associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), head of the Soft and Micro Robotics Laboratory within the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE), and the senior author of an open-access paper on the new design.

Chen is joined on the paper by co-lead authors Suhan Kim and Yi-Hsuan Hsiao, who are EECS graduate students; as well as EECS graduate student Zhijian Ren and summer visiting student Jiashu Huang. The research appears today in Science Robotics.

Boosting performance

Prior versions of the robotic insect were composed of four identical units, each with two wings, combined into a rectangular device about the size of a microcassette.

“But there is no insect that has eight wings. In our old design, the performance of each individual unit was always better than the assembled robot,” Chen says.

This performance drop was partly caused by the arrangement of the wings, which would blow air into each other when flapping, reducing the lift forces they could generate.

The new design chops the robot in half. Each of the four identical units now has one flapping wing pointing away from the robot’s center, stabilizing the wings and boosting their lift forces. With half as many wings, this design also frees up space so the robot could carry electronics.

In addition, the researchers created more complex transmissions that connect the wings to the actuators, or artificial muscles, that flap them. These durable transmissions, which required the design of longer wing hinges, reduce the mechanical strain that limited the endurance of past versions.

“Compared to the old robot, we can now generate control torque three times larger than before, which is why we can do very sophisticated and very accurate path-finding flights,” Chen says.

Yet even with these design innovations, there is still a gap between the best robotic insects and the real thing. For instance, a bee has only two wings, yet it can perform rapid and highly controlled motions.

“The wings of bees are finely controlled by a very sophisticated set of muscles. That level of fine-tuning is something that truly intrigues us, but we have not yet been able to replicate,” he says.

Less strain, more force

The motion of the robot’s wings is driven by artificial muscles. These tiny, soft actuators are made from layers of elastomer sandwiched between two very thin carbon nanotube electrodes and then rolled into a squishy cylinder. The actuators rapidly compress and elongate, generating mechanical force that flaps the wings.

In previous designs, when the actuator’s movements reach the extremely high frequencies needed for flight, the devices often start buckling. That reduces the power and efficiency of the robot. The new transmissions inhibit this bending-buckling motion, which reduces the strain on the artificial muscles and enables them to apply more force to flap the wings.

Another new design involves a long wing hinge that reduces torsional stress experienced during the flapping-wing motion. Fabricating the hinge, which is about 2 centimeters long but just 200 microns in diameter, was among their greatest challenges.

“If you have even a tiny alignment issue during the fabrication process, the wing hinge will be slanted instead of rectangular, which affects the wing kinematics,” Chen says.

After many attempts, the researchers perfected a multistep laser-cutting process that enabled them to precisely fabricate each wing hinge.

With all four units in place, the new robotic insect can hover for more than 1,000 seconds, which equates to almost 17 minutes, without showing any degradation of flight precision.

“When my student Nemo was performing that flight, he said it was the slowest 1,000 seconds he had spent in his entire life. The experiment was extremely nerve-racking,” Chen says.

The new robot also reached an average speed of 35 centimeters per second, the fastest flight researchers have reported, while performing body rolls and double flips. It can even precisely track a trajectory that spells M-I-T.

“At the end of the day, we’ve shown flight that is 100 times longer than anyone else in the field has been able to do, so this is an extremely exciting result,” he says.

From here, Chen and his students want to see how far they can push this new design, with the goal of achieving flight for longer than 10,000 seconds.

They also want to improve the precision of the robots so they could land and take off from the center of a flower. In the long run, the researchers hope to install tiny batteries and sensors onto the aerial robots so they could fly and navigate outside the lab.

“This new robot platform is a major result from our group and leads to many exciting directions. For example, incorporating sensors, batteries, and computing capabilities on this robot will be a central focus in the next three to five years,” Chen says.

###

This research is funded, in part, by the U.S. National Science Foundation and a Mathworks Fellowship.

END

This fast and agile robotic insect could someday aid in mechanical pollination

With a new design, the bug-sized bot was able to fly 100 times longer than prior versions.

2025-01-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers identify novel immune cells that may worsen asthma

2025-01-15

Hamilton, ON (January 15, 2025) – Researchers at McMaster University have made an important discovery in the field of asthma research, identifying a new population of immune cells that may play a crucial role in the severity of asthma symptoms.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine on Jan. 15, 2025, sheds light on the complex mechanisms behind severe asthma and opens new avenues for potential treatments.

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, leading to difficulty breathing. Severe ...

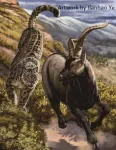

Conquest of Asia and Europe by snow leopards during the last Ice Ages uncovered

2025-01-15

The study, published in Science Advances, was led by researchers Qigao Jiangzuo, from Peking University, and Joan Madurell Malapeira, from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB).

Snow leopards (Panthera uncia) are in serious danger of extinction, with only about 4,000 specimens remaining. They are medium to large felids that live at high altitudes, over 2,000 meters above sea level, mainly in the Himalayas. Although their distinctive traits have long been recognized, the correlation between these ...

Researchers make comfortable materials that generate power when worn

2025-01-15

Researchers have demonstrated new wearable technologies that both generate electricity from human movement and improve the comfort of the technology for the people wearing them. The work stems from an advanced understanding of materials that increase comfort in textiles and produce electricity when they rub against another surface.

At issue are molecules called amphiphiles, which are often used in consumer products to reduce friction against human skin. For example, amphiphiles are often incorporated into diapers to prevent chafing.

“We set out to develop a model that would give us ...

Study finding Xenon gas could protect against Alzheimer’s disease leads to start of clinical trial

2025-01-15

Most treatments being pursued today to protect against Alzheimer’s disease focus on amyloid plaques and tau tangles that accumulate in the brain, but new research from Mass General Brigham and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis points to a novel—and noble—approach: using Xenon gas. The study found that Xenon gas inhalation suppressed neuroinflammation, reduced brain atrophy, and increased protective neuronal states in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Results are published in Science Translational Medicine, and a phase 1 clinical trial of the treatment in healthy volunteers will begin in early 2025.

“It ...

Protein protects biological nitrogen fixation from oxidative stress

2025-01-15

A small helper for big tasks: an oxygen sensor protein protects the enzymatic machinery of biological nitrogen fixation from serious damage. Its use in biotechnology could help to reduce the use of synthetic fertiliser in agriculture in the future. A research team led by biochemist Prof. Dr Oliver Einsle from the Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy and the Centre for Biological Signalling Studies (BIOSS) at the University of Freiburg has discovered exactly how the so-called Shethna protein II works. The scientists used the newly established cryo-electron microscopy in Freiburg. ...

Three-quarters of medical facilities in Mariupol sustained damage during Russia’s siege of 2022

2025-01-15

Three-quarters of medical facilities in Mariupol sustained damage during Russia’s siege of 2022, with some evidence that the attacks may have been intentionally targeted, per study using satellite imagery.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0003950

Article Title: The effect of conflict on damage to medical facilities in Mariupol, Ukraine: a quasi-experimental study

Author Countries: Germany, United States

Funding: This work was supported ...

Snow leopard fossils clarify evolutionary history of species

2025-01-15

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is a large feline unique to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its surrounding areas. As the apex predator in the region, the snow leopard plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological stability. Its unique characteristics, coupled with its striking appearance, have made it a flagship species for conservation efforts aimed at protecting the ecosystem of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

Unfortunately, few snow leopard fossils have been found in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau region, particularly fossils from the Quaternary period. As a result, it’s unclear how snow leopards evolved their specialized adaptations to this environment.

On the one hand, molecular ...

Machine learning outperforms traditional statistical methods in addressing missing data in electronic health records

2025-01-15

Researchers from the National Institute of Health Data Science at Peking University and the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Peking University People's Hospital have conducted a comprehensive systematic review evaluating strategies for addressing missing data in electronic health records (EHRs). Published in Health Data Science, the study highlights the growing importance of machine learning methods over traditional statistical approaches in managing missing data scenarios effectively.

Electronic health records have become a cornerstone in modern healthcare research, enabling analysis across clinical trials, treatment effectiveness studies, and ...

AI–guided lung ultrasound by nonexperts

2025-01-15

About The Study: In this multicenter validation study, trained health care professionals with artificial intelligence (AI) assistance achieved lung ultrasound images meeting diagnostic standards compared with lung ultrasound experts without AI. This technology could extend access to lung ultrasound to underserved areas lacking expert personnel.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Cristiana Baloescu, MD, MPH, email cristiana.baloescu@yale.edu.

To access the embargoed ...

Prevalence of and inequities in poor mental health across 3 US surveys

2025-01-15

About The Study: This survey study documents increasingly prevalent poor mental health from 2011 to 2022 across multiple U.S. health surveys, with notable prevalence differences in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and National Survey on Drug Use and Health vs National Health Interview Survey. Inequities in these outcomes by age, sex, and racial and ethnic group were often sizeable and changed over time in distinct ways, consistent with findings in prior literature.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Massage Therapy Foundation awards $300,000 research grant to the University of Denver

Gastrointestinal toxicity linked to targeted cancer therapies in the United States

Countdown to the Bial Award in Biomedicine 2025

Blood marker from dementia research could help track aging across the animal world

Birds change altitude to survive epic journeys across deserts and seas

Here's why you need a backup for the map on your phone

ACS Central Science | Researchers from Insilico Medicine and Lilly publish foundational vision for fully autonomous “Prompt-to-Drug” pharmaceutical R&D

Increasing the number of coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction does not appear to reduce death rates

Tackling uplift resistance in tall infrastructures sustainably

Novel wireless origami-inspired smart cushioning device for safer logistics

Hidden genetic mismatch, which triples the risk of a life-threatening immune attack after cord blood transplantation

Physical function is a crucial predictor of survival after heart failure

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

[Press-News.org] This fast and agile robotic insect could someday aid in mechanical pollinationWith a new design, the bug-sized bot was able to fly 100 times longer than prior versions.