(Press-News.org) Scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Harvard Medical School, and McLean Hospital have discovered a surprising mechanism by which the inherited genetic mutation known to cause Huntington’s disease leads to the death of brain cells. The findings change the understanding of the fatal neurodegenerative disorder and suggest potential ways to delay or even prevent it.

For 30 years, researchers have known that Huntington’s is caused by an inherited mutation in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene, but they didn’t know how the mutation causes brain cell death. A new study published today in Cell reveals that the inherited mutation doesn’t itself harm cells. Rather, the mutation is innocuous for decades but slowly morphs into a highly toxic form that then quickly kills the cell.

The Huntington’s mutation involves a stretch of DNA in the HTT gene in which a three-letter sequence of DNA, “CAG,” is repeated at least 40 times, as opposed to the 15-35 repeats inherited by people without the disease. The researchers found that DNA tracts with 40 or more CAG repeats grow until they are hundreds of repeats long. This type of “somatic expansion” occurs in only the specific types of brain cells that later die in Huntington’s disease. Only once a cell's DNA expansion reaches a threshold number of CAGs — roughly 150 — does the cell sicken and then die. The cumulative death of many such cells leads to the symptoms of Huntington’s disease.

The study offers a potential explanation as to why candidate Huntington’s drugs that aim to reduce expression of the HTT protein have struggled in clinical trials: Very few cells have the toxic version of the protein at any given time, so the treatments may not be having a therapeutic effect in most cells.

The research also elevates a different therapeutic strategy: Stopping or slowing the CAG-repeat expansion in the HTT gene might postpone toxicity in a far larger number of cells, delaying or even preventing the onset of the disease.

“These experiments have changed how we think about how Huntington’s develops,” said Steve McCarroll, a geneticist and neuroscientist and co-senior author of the study. McCarroll is an institute member and director of genomic neurobiology at the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad, the Dorothy and Milton Flier Professor of Biomedical Science and Genetics at Harvard Medical School, and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “This is a really different way of thinking about how a mutation brings about a disease, and we think that it will apply in DNA-repeat disorders beyond Huntington's disease.”

“The point of our work — what we all do — is relieving suffering caused by disease,” said co-senior author Sabina Berretta, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, a member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system. She is also the director of the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (HBTRC), an NIH NeuroBioBank center at McLean Hospital. “This study and the work it informs could be impactful and make a major difference in relieving suffering in the short term.”

Bob Handsaker, a staff scientist, Seva Kashin, a senior principal software engineer, and former research associate Nora Reed, all from McCarroll’s group, are co-first authors on the work.

Open questions

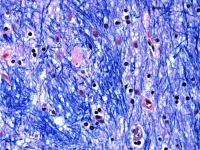

Huntington’s disease kills a population of cells called striatal projection neurons, which are located in the striatum, a structure deep in the brain responsible for movement, many cognitive functions, and motivation. When large numbers of these cells die, patients develop involuntary movements in the arms, legs, and face, and many patients also develop cognitive problems. These symptoms typically begin in mid-life and then progress over 10 to 20 years to more severe cognitive problems and difficulty moving or swallowing.

In 1993, researchers discovered that the disease is caused by an expanded stretch of CAGs in the HTT gene. Most people inherit versions of the gene with 15 to 35 consecutive CAGs and never develop Huntington’s, but those who inherit a version with 40 or more consecutive CAGs almost always develop the illness later in life. The longer the stretch of repeats, the younger a person tends to be when symptoms first appear. The tract of repeated CAGs has also been shown to expand over time, resulting in a variety of lengths in different tissues.

But underlying biological questions had always lingered: How is the HTT mutation toxic? Why would the HTT protein — which appears in almost every cell in the body — kill only some brain cells and not others? And why do patients, who are born with the mutation and express the protein throughout life, develop symptoms only in middle age, after decades of apparent good health?

Repeat expansion

To answer these questions, the research team built upon a technology the McCarroll lab developed a decade ago called droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing (Drop-seq), which allows researchers to analyze gene expression in thousands of single cells. Seeking to understand the direct biological effects of CAG-repeat length, the researchers adapted single-cell RNA-sequencing to help them determine not only gene expression and the identity of single cells, but also the length of DNA repeat tracts inside each cell.

“It’s been known that these repeats expand in neurons,” said Kashin. “But the ability to take a particular cell and measure both the CAG length and the transcriptional profile — that’s a really important underpinning that’s allowed for really powerful analysis.”

The researchers studied brain tissue donated by 53 people with Huntington’s and 50 without the disease, collected and preserved by the HBTRC. They analyzed more than 500,000 single cells and found that most cell types from people with the disease had essentially the same CAG repeat that they had inherited. But striatal projection neurons — the primary striatal cells that die in the disease — had greatly expanded their CAG-repeat tracts. Most previous research on human brain tissue had focused on CAG-repeat tracts of fewer than 100 repeats, but the new study showed that some neurons had as many as 800 CAGs, confirming a discovery made 20 years ago by Peggy Shelbourne at the University of Glasgow.

Most surprisingly, the research team found that expansion of the DNA repeat from 40 to 150 CAGs had no apparent effect on the neurons' health. But neurons whose repeats exceeded 150 CAGs showed greatly distorted gene expression, losing expression of critical genes and then dying.

McCarroll’s team also used computer modeling of the experimental data to estimate the rate and timing of CAG-repeat expansion in striatal projection neurons. They found that CAG-repeat tracts initially grow slowly, expanding less than once a year during the first two decades of life. But when a cell's repeat tract reaches about 80 CAGs — usually after several decades — its rate of expansion accelerates dramatically and it expands to 150 CAGs in only a few more years. The cell then dies just months later. This means that a neuron spends more than 95 percent of its life with an innocuous HTT gene. Moreover, because the CAG-repeat tracts in different cells cross this toxicity threshold at different times, the cells, as a group, disappear slowly over a long period, starting about 20 years before symptoms appear and more quickly as symptoms commence.

“A lot was known about Huntington's disease before we started this work, but there were gaps and inconsistencies in our collective understanding,” Handsaker said. “We've been able to piece together the full trajectory of the pathology as it unfolds over decades in individual neurons, and that gives us potentially many different time points at which we can intervene therapeutically.”

Analyzing brain tissue contributed by Huntington’s patients was critical for the work. “Our gratitude is with the families that chose to do something that is very difficult to do,” Berretta said. “This would not have been possible without the altruism of many brain donors who have left a legacy of knowledge that will last and benefit many other people.”

Therapeutic possibilities

McCarroll’s team suggests that rather than targeting the HTT protein, a complementary or potentially better therapeutic approach could be to slow or stop the DNA-repeat expansion, which could help delay or even prevent the disease.

Previous genetic studies of Huntington’s, including studies by Vanessa Wheeler and Ricardo Mouro Pinto at Massachusetts General Hospital, hint at possible ways to slow this expansion. The studies showed that cellular proteins involved in maintaining and repairing DNA sometimes undermine the stability of DNA-repeat tracts. For example, the MSH3 protein normally helps the cell monitor its DNA for potential mutations, but loops in the DNA formed by extra CAGs can confuse this protein into expanding the CAG repeat. An international team of human geneticists found that common genetic variations in the genes encoding these DNA-repair proteins can hasten or delay onset of symptoms in Huntington’s patients — findings that McCarroll says directly inspired his team's focus on developing ways to measure the CAG repeat in single cells. He adds that slowing down certain DNA-maintenance processes with a molecular therapy might slow down DNA-repeat expansion by allowing other less error-prone DNA-repair mechanisms to resolve these loops.

In the meantime, the researchers are working to understand how DNA-repeat tracts longer than 150 CAGs lead to neuronal impairment and death, and why repeats expand more in some kinds of neurons than in others. They are also using a similar combination of single-cell RNA sequencing alongside DNA-repeat profiling to understand the connection between DNA-repeat expansion and cellular changes in other genetic disorders involving DNA repeats and late onset in patients. More than 50 human brain disorders, including fragile X syndrome and myotonic dystrophy, are caused by expansions of DNA repeats in various genes.

“It’s going to take much scientific work by many people to get to treatments that slow the expansion of DNA repeats,” McCarroll said. “But we’re hopeful that understanding this as the central disease-driving process leads to deep focus and new options.”

***

Funding

This work was supported by CHDI Foundation, Inc., the Department of Genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, the Ludwig Neurodegenerative Disease Seed Grants Program at Harvard Medical School, and the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Paper cited

Handsaker RE, Kashin S, Reed NM, et al. Long somatic DNA-repeat expansion drives neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. Cell. Online January 16, 2025. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.038.

About Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was launched in 2004 to empower this generation of creative scientists to transform medicine. The Broad Institute seeks to describe the molecular components of life and their connections; discover the molecular basis of major human diseases; develop effective new approaches to diagnostics and therapeutics; and disseminate discoveries, tools, methods and data openly to the entire scientific community.

Founded by MIT, Harvard, Harvard-affiliated hospitals, and the visionary Los Angeles philanthropists Eli and Edythe L. Broad, the Broad Institute includes faculty, professional staff and students from throughout the MIT and Harvard biomedical research communities and beyond, with collaborations spanning over a hundred private and public institutions in more than 40 countries worldwide.

About McLean Hospital

McLean Hospital has a continuous commitment to put people first in patient care, innovation and discovery, and shared knowledge related to mental health. It is consistently named the #1 freestanding psychiatric hospital in the United States by U.S. News & World Report, and is #2 in America for psychiatric care in 2023-24. McLean Hospital is the largest psychiatric affiliate of Harvard Medical School and a member of Mass General Brigham. To stay up to date on McLean, follow us on Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn.

END

Study finds surprising way that genetic mutation causes Huntington’s disease, transforming understanding of the disorder

Researchers studying brain cells from Huntington’s patients show that the mutation, which changes over decades, becomes toxic only later in life.

2025-01-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

DNA motors found to switch gears

2025-01-16

Scientists from Delft, Vienna, and Lausanne discovered that the protein machines that shape our DNA can switch direction. Until now, researchers believed that these so-called SMC motors that make loops into DNA could move in one direction only. The discovery, which is published in Cell, is key to understanding how these motors shape our genome and regulate our genes.

Connecting DNA

“Sometimes, a cell needs to be quick in changing which genes should be expressed and which ones should be turned off, for example in response to food, alcohol or heat. To turn genes off and on, cells use Structural Maintenance ...

Human ancestor thrived longer in harsher conditions than previous estimates

2025-01-16

An early human ancestor of our species successfully navigated harsher and more arid terrains for longer in Eastern Africa than previously thought, according to a new study published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Homo erectus, the first of our relatives to have human-like proportions and the first known early human to migrate out of Africa, was the focus of the new study led by the international research team.

The researchers analysed evidence from Engaji Nanyori in Tanzania’s Oldupai Gorge, revealing Homo erectus thrived ...

Evolution: Early humans adapted to extreme desert conditions over one million years ago

2025-01-16

Homo erectus was able to adapt to and survive in desert-like environments at least 1.2 million years ago, according to a paper published in Communications Earth & Environment. The findings suggest that behavioural adaptations included returning repeatedly over thousands of years to specific rivers and ponds for fresh water, and the development of specialised tools. The authors propose that this capability to adapt may have led to the expansion of H. erectus’ geographic range.

There has been significant debate over ...

Race and ethnicity and diffusion of telemedicine in Medicaid for schizophrenia care after onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

2025-01-16

About The Study: In this cohort study of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia, telemental health care diffused rapidly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in state-operated agencies. Together, agency-level and beneficiary-level race and ethnicity findings suggest within-agency racial and ethnic differences in diffusion of telemental health care. States should monitor the diffusion of innovations across vulnerable populations.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Sharon-Lise Normand, PhD, email sharon@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

Embed this link to provide your readers free access to the full-text article This ...

Changes in support for advance provision and over-the-counter access to medication abortion

2025-01-16

About The Study: In this serial cross-sectional analysis of people ages 15 to 49 before Dobbs and 1 year after Dobbs, findings suggested that national support for expanded access to medication abortion has grown. Alternative models of care, such as advance provision and over-the-counter, have the potential to offer a promising approach to abortion care, particularly for people living in abortion-restricted states.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, M. Antonia Biggs, PhD, email antonia.biggs@ucsf.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

Protein level predicts immunotherapy response in bowel cancer

2025-01-16

Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00hrs GMT Thursday 16 January 2025

Peer reviewed

Observational study

People and cells

Protein level predicts immunotherapy response in bowel cancer

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, have shown that the amount of a protein called CD74 can indicate which people with bowel cancer may respond best to immunotherapy.

If integrated into the clinic, testing for this protein could potentially allow hundreds of previously ineligible patients to benefit ...

The staying power of bifocal contact lens benefits in young kids

2025-01-16

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Young nearsighted kids who wear bifocal contact lenses that slow uncoordinated eye growth do not lose the benefits of the treatment once they stop wearing the lenses, new research shows.

The study is a follow-up to a clinical trial published in 2020 showing that soft multifocal contact lenses with a heavy dose of added reading power dramatically slowed further progression of myopia in kids as young as 7 years old. Researchers wondered if discontinuing that treatment might cause a rebound of faster-than-normal eye growth that wipes out the benefit.

In the new trial, nearsighted kids wore ...

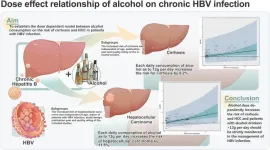

Dose-dependent relationship between alcohol consumption and the risks of hepatitis b virus-associated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis and systematic review

2025-01-16

Background and Aims

The quantitative effects of alcohol consumption on cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection are unknown. This study aimed to establish a dose-dependent model of alcohol consumption on the risks of cirrhosis and HCC.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and four Chinese databases were searched for studies published from their inception to 15 May 2024. A random-effects model was used to pool the data on the incidence of cirrhosis and HCC, and a dose-dependent model of alcohol’s effect on cirrhosis and HCC was established.

Results

A total of 33,272 HBV patients ...

International Alliance for Primary Immunodeficiency Societies selects Rockefeller University Press to publish new Journal of Human Immunity

2025-01-16

January 16, 2025 – New York, NY – The International Alliance for Primary Immunodeficiency Societies (IAPIDS) and Rockefeller University Press (RUP) have entered a partnership to launch Journal of Human Immunity (JHI), the official open access journal of IAPIDS. This collaboration will ensure that JHI emerges as the destination for exciting research into human immunity, with a particular focus on inborn errors of immunity.

“The Journal of Human Immunity represents a bold step forward in advancing ...

Leader in mission-driven open publishing wins APE Award for Innovation in Scholarly Communication

2025-01-16

Digital Science is pleased to announce that Dr Raym Crow, a leading figure in mission-driven, sustainable open publishing models, has won the 2025 APE Award for Innovation in Scholarly Communication.

The award – a joint initiative between Digital Science and the Berlin Institute for Scholarly Publishing (BISP) – has been announced at the 20th Academic Publishing in Europe (APE) Conference in Berlin, Germany.

The APE award is presented to an individual who has brought innovation in scholarly communication to the community, through infrastructure, technology, business models, output on the topic, theory, or practice.

With more than ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] Study finds surprising way that genetic mutation causes Huntington’s disease, transforming understanding of the disorderResearchers studying brain cells from Huntington’s patients show that the mutation, which changes over decades, becomes toxic only later in life.