(Press-News.org) When we think about the immune system, we usually associate it with fighting infections. However, a study published in Science by the Champalimaud Foundation reveals a surprising new role. During periods of low energy—such as intermittent fasting or exercise—immune cells step in to regulate blood sugar levels, acting as the “postman” in a previously unknown three-way conversation between the nervous, immune and hormonal systems. These findings open up new approaches for managing conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cancer.

Rethinking the Immune System

“For decades, immunology has been dominated by a focus on immunity and infection”, says Henrique Veiga-Fernandes, head of the Immunophysiology Lab at the Champalimaud Foundation. “But we’re starting to realise the immune system does a lot more than that”.

Glucose, a simple sugar, is the primary fuel for our brains and muscles. Maintaining stable blood sugar levels is crucial for our survival, especially during fasting or prolonged physical activity when energy demands are high and food intake is low.

Traditionally, blood sugar regulation has been attributed to the hormones insulin and glucagon, both produced by the pancreas. Insulin lowers blood glucose by promoting its uptake into cells, while glucagon raises it by signalling the liver to release glucose from stored sources.

Veiga-Fernandes and his team suspected there was more to the story. “For example”, he notes, “some immune cells regulate how the body absorbs fat from food, and we’ve recently shown that brain-immune interactions help control fat metabolism and obesity. This got us thinking—could the nervous and immune systems collaborate to regulate other key processes, like blood sugar levels?”.

A New Circuit Uncovered

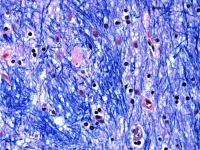

To explore this idea, the researchers conducted experiments in mice. They used genetically engineered mice lacking specific immune cells to observe their effects on blood sugar levels.

They discovered that mice missing a type of immune cell called ILC2 couldn’t produce enough glucagon—the hormone that raises blood sugar—and their glucose levels dropped too low. “When we transplanted ILC2s into these deficient mice, their blood sugar returned to normal, confirming the role of these immune cells in stabilising glucose when energy is scarce”, explains Veiga-Fernandes.

Realising that the immune system could affect a hormone as vital as glucagon, the team knew they were onto something of major impact. But it left them asking: how exactly does this process work? The answer took them in a very unexpected direction.

“We thought this was all being regulated in the liver because that’s where glucagon exerts its function”, recalls Veiga-Fernandes. “But our data kept telling us that everything of importance was happening between the intestine and the pancreas”.

Using advanced cell-tagging methods, the team labelled ILC2 cells in the gut, giving them a glow-in-the-dark marker. After fasting, they found these cells had travelled to the pancreas. “One of the biggest surprises was finding that the immune system stimulates the production of the hormone glucagon by sending immune cells on a journey across different organs”.

Once in the pancreas, those immune cells release cytokines—tiny chemical messengers—that instruct pancreatic cells to produce the hormone glucagon. The increase in glucagon then signals the liver to release glucose. “When we blocked these cytokines, glucagon levels dropped, proving they are essential for maintaining blood sugar levels”.

“What’s remarkable here is that we’re seeing mass migration of immune cells between the intestine and pancreas, even in the absence of infection,” he adds. “This shows that immune cells aren’t just battle-hardened soldiers fighting off threats—they also act like emergency responders, stepping in to deliver critical energy supplies and maintain stability in times of need”.

It turns out this migration is orchestrated by the nervous system. During fasting, neurons in the gut connected to the brain release chemical signals that bind to immune cells, telling them to leave the intestine and go to a new “postcode” in the pancreas, within a few hours. The study showed that these nerve signals change the activity of immune cells, suppressing genes that anchor them in the intestine and enabling them to move to where they’re needed.

Implications for Fasting and Exercise

“This is the first evidence of a complex neuroimmune-hormonal circuit”, Veiga-Fernandes observes. “It shows how the nervous, immune, and hormonal systems work together to enable one of the body’s most essential processes—producing glucose when energy is scarce”.

“Mice share many fundamental biological systems with humans, suggesting this inter-organ dialogue also occurs in humans when fasting or exercising. By understanding the role of ILC2s and their regulation by the nervous system, we can better appreciate how these daily life activities support metabolic health. We’re eavesdropping on conversations between organs that we’ve never heard before”.

He adds that the immune system likely evolved as a safeguard during adversity, pointing out that our ancestors didn’t have the luxury of three meals a day and, if they were lucky, might have managed just one. This evolutionary pressure would have pressured our bodies to find ways to ensure that every cell gets the energy it needs.

“We’ve long known that the brain can directly signal the pancreas to release hormones quickly, but our work shows it can also indirectly boost glucagon production via immune cells, making the body better equipped to handle fasting and intense physical activity efficiently”.

Cancer, Diabetes and Beyond

The findings could open new doors for managing a range of conditions, notably for cancer research. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours and liver cancer can hijack the body’s metabolic processes, using glucagon to increase glucose production and fuel their growth. In advanced liver cancer, this process can lead to cancer-related cachexia, a condition marked by severe weight and muscle loss. Understanding these mechanisms could help develop better treatments.

“Balancing blood sugar is also critical, not only for preventing obesity, but also for addressing the global diabetes epidemic, which affects hundreds of millions of people”, remarks Veiga-Fernandes. “Targeting these neuro-immune pathways could offer a new approach to prevention and treatment”.

“This study reveals a level of communication between body systems that we’re only beginning to grasp”, he concludes. “We want to understand how this inter-organ communication works—or doesn’t—in people with cancer, chronic inflammation, high stress, or obesity. Ultimately, we aim to harness these results to improve therapies for hormonal and metabolic disorders”.

END

Eavesdropping on organs: Immune system controls blood sugar levels

2025-01-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Quantum engineers ‘squeeze’ laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors

2025-01-16

The trick to creating a better quantum sensor? Just give it a little squeeze.

For the first time ever, scientists have used a technique called “quantum squeezing” to improve the gas sensing performance of devices known as optical frequency comb lasers. These ultra-precise sensors are like fingerprint scanners for molecules of gas. Scientists have used them to spot methane leaks in the air above oil and gas operations and signs of COVID-19 infections in breath samples from humans.

Now, in a series of lab experiments, researchers have laid out a path for making those kinds of measurements even more sensitive and faster—doubling the speed of ...

New study reveals how climate change may alter hydrology of grassland ecosystems

2025-01-16

New research co-led by the University of Maryland reveals that drought and increased temperatures in a CO2-rich climate can dramatically alter how grasslands use and move water. The study provides the first experimental demonstration of the potential impacts of climate change on water movement through grassland ecosystems, which make up nearly 40% of Earth’s land area and play a critical role in Earth’s water cycle. The study appears in the January 17, 2025, issue of the journal Science.

“If we want to predict the effects of climate change ...

Polymer research shows potential replacement for common superglues with a reusable and biodegradable alternative

2025-01-16

EMBARGO: THIST CONTENT IS UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 2 PM U.S. EASTERN STANDARD TIME ON JANUARY 16, 2025. INTERESTED MEDIA MAY RECIVE A PREVIEW COPY OF THE JOURNAL ARTICLE IN ADVANCE OF THAT DATE OR CONDUCT INTERVIEWS, BUT THE INFORMATION MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, OR POSTED ONLINE UNTIL AFTER THE RELEASE WINDOW.

Researchers at Colorado State University and their partners have developed an adhesive polymer that is stronger than current commercially available options while also being biodegradable ...

Research team receives $1.5 million to study neurological disorders linked to long COVID

2025-01-16

The National Institute of Mental Health has awarded a significant grant of $1.5 million to Jianyang Du, PhD, of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, for a research study aimed at uncovering the cellular and molecular mechanisms that lead to neurological disorders caused by long COVID-19.

Dr. Du is an associate professor at the College of Medicine in the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology. Colleen Jonsson, PhD, director of the UT Health Science Center Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and professor in the Department of Microbiology, is co-investigator on the grant, and Kun Li, PhD, assistant ...

Research using non-toxic bacteria to fight high-mortality cancers prepares for clinical trials

2025-01-16

A University of Massachusetts Amherst-Ernest Pharmaceuticals team of scientists has made “exciting,” patient-friendly advances in developing a non-toxic bacterial therapy, BacID, to deliver cancer-fighting drugs directly into tumors. This emerging technology holds promise for very safe and more effective treatment of cancers with high mortality rates, including liver, ovarian and metastatic breast cancer.

Clinical trials with participating cancer patients are estimated to begin in 2027. “This is exciting because we now have all the critical pieces for getting an effective bacterial ...

Do parents really have a favorite child? Here’s what new research says

2025-01-16

Siblings share a unique bond built from shared memories, family rituals and the occasional argument. But ask almost anyone with a brother or sister and you’ll likely find a longstanding debate: who’s the favorite? New research from BYU sheds some light on that playful rivalry, revealing how parents might subtly show favoritism based on birth order, personality and gender.

The study, conducted by BYU School of Family Life professor Alex Jensen, found that younger siblings generally receive more favorable ...

Mussel bed surveyed before World War II still thriving

2025-01-16

A mussel bed along Northern California’s Dillon Beach is as healthy and biodiverse as it was about 80 years ago, when two young students surveyed it shortly before Pearl Harbor was attacked and one was sent to fight in World War II.

Their unpublished, typewritten manuscript sat in the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory’s library for years until UC Davis scientists found it and decided to resurvey the exact same mussel bed with the old paper’s meticulous photos and maps directing their way.

The new findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, document ...

ACS Annual Report: Cancer mortality continues to drop despite rising incidence in women; rates of new diagnoses under 65 higher in women than men

2025-01-16

ATLANTA, January 16, 2025 — The American Cancer Society (ACS) today released Cancer Statistics, 2025, the organization’s annual report on cancer facts and trends. The new findings show the cancer mortality rate declined by 34% from 1991 to 2022 in the United States, averting approximately 4.5 million deaths. However, this steady progress is jeopardized by increasing incidence for many cancer types, especially among women and younger adults, shifting the burden of disease. For example, incidence rates in women 50-64 years of age have surpassed those in ...

Fewer skin ulcers in Werner syndrome patients treated with pioglitazone

2025-01-16

“[…] the results of this study indicate that pioglitazone might be useful in treating refractory skin ulcers, a typical condition that reduces the quality of life of patients with WS.”

BUFFALO, NY- January 16, 2025 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as “Aging (Albany NY)” and “Aging-US” by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 22 on December 2, 2024, entitled “Less frequent skin ulcers among patients with Werner syndrome treated with pioglitazone: findings from the Japanese Werner Syndrome Registry.”

Scientists ...

Study finds surprising way that genetic mutation causes Huntington’s disease, transforming understanding of the disorder

2025-01-16

Scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Harvard Medical School, and McLean Hospital have discovered a surprising mechanism by which the inherited genetic mutation known to cause Huntington’s disease leads to the death of brain cells. The findings change the understanding of the fatal neurodegenerative disorder and suggest potential ways to delay or even prevent it.

For 30 years, researchers have known that Huntington’s is caused by an inherited mutation in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene, but they didn’t ...