(Press-News.org) You can probably complete an amazing number of tasks with your hands without looking at them. But if you put on gloves that muffle your sense of touch, many of those simple tasks become frustrating. Take away proprioception — your ability to sense your body’s relative position and movement — and you might even end up breaking an object or injuring yourself.

“Most people don’t realize how often they rely on touch instead of vision — typing, walking, picking up a flimsy cup of water,” said Charles Greenspon, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of Chicago. “If you can’t feel, you have to constantly watch your hand while doing anything, and you still risk spilling, crushing or dropping objects.”

Greenspon and his research collaborators recently published papers in Nature Biomedical Engineering and Science documenting major progress on a technology designed to address precisely this problem: direct, carefully timed electrical stimulation of the brain that can recreate tactile feedback to give nuanced “feeling” to prosthetic hands.

The science of restoring sensation

These new studies build on years of collaboration among scientists and engineers at UChicago, the University of Pittsburgh, Northwestern University, Case Western Reserve University and Blackrock Neurotech. Together they are designing, building, implementing and refining brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and robotic prosthetic arms aimed at restoring both motor control and sensation in people who have lost significant limb function.

On the UChicago side, the research was led by neuroscientist Sliman Bensmaia, PhD, until his unexpected passing in 2023.

The researchers’ approach to prosthetic sensation involves placing tiny electrode arrays in the parts of the brain responsible for moving and feeling the hand. On one side, a participant can move a robotic arm by simply thinking about movement, and on the other side, sensors on that robotic limb can trigger pulses of electrical activity called intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) in the part of the brain dedicated to touch.

For about a decade, Greenspon explained, this stimulation of the touch center could only provide a simple sense of contact in different places on the hand.

“We could evoke the feeling that you were touching something, but it was mostly just an on/off signal, and often it was pretty weak and difficult to tell where on the hand contact occurred,” he said.

The newly published results mark important milestones in moving past these limitations.

Advancing understanding of artificial touch

In the first study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, Greenspon and his colleagues focused on ensuring that electrically evoked touch sensations are stable, accurately localized and strong enough to be useful for everyday tasks.

By delivering short pulses to individual electrodes in participants’ touch centers and having them report where and how strongly they felt each sensation, the researchers created detailed “maps” of brain areas that corresponded to specific parts of the hand. The testing revealed that when two closely spaced electrodes are stimulated together, participants feel a stronger, clearer touch, which can improve their ability to locate and gauge pressure on the correct part of the hand.

The researchers also conducted exhaustive tests to confirm that the same electrode consistently creates a sensation corresponding to a specific location.

“If I stimulate an electrode on day one and a participant feels it on their thumb, we can test that same electrode on day 100, day 1,000, even many years later, and they still feel it in roughly the same spot,” said Greenspon, who was the lead author on this paper.

From a practical standpoint, any clinical device would need to be stable enough for a patient to rely on it in everyday life. An electrode that continually shifts its “touch location” or produces inconsistent sensations would be frustrating and require frequent recalibration. By contrast, the long-term consistency this study revealed could allow prosthetic users to develop confidence in their motor control and sense of touch, much as they would in their natural limbs.

Adding feelings of movement and shapes

The complementary Science paper went a step further to make artificial touch even more immersive and intuitive. The project was led by first author Giacomo Valle, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow at UChicago who is now continuing his bionics research at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

“Two electrodes next to each other in the brain don’t create sensations that ‘tile’ the hand in neat little patches with one-to-one correspondence; instead, the sensory locations overlap,” explained Greenspon, who shared senior authorship of this paper with Bensmaia.

The researchers decided to test whether they could use this overlapping nature to create sensations that could let users feel the boundaries of an object or the motion of something sliding along their skin. After identifying pairs or clusters of electrodes whose “touch zones” overlapped, the scientists activated them in carefully orchestrated patterns to generate sensations that progressed across the sensory map.

Participants described feeling a gentle gliding touch passing smoothly over their fingers, despite the stimulus being delivered in small, discrete steps. The scientists attribute this result to the brain’s remarkable ability to stitch together sensory inputs and interpret them as coherent, moving experiences by “filling in” gaps in perception.

The approach of sequentially activating electrodes also significantly improved participants’ ability to distinguish complex tactile shapes and respond to changes in the objects they touched. They could sometimes identify letters of the alphabet electrically “traced” on their fingertips, and they could use a bionic arm to steady a steering wheel when it began to slip through the hand.

These advancements help move bionic feedback closer to the precise, complex, adaptive abilities of natural touch, paving the way for prosthetics that enable confident handling of everyday objects and responses to shifting stimuli.

The future of neuroprosthetics

The researchers hope that as electrode designs and surgical methods continue to improve, the coverage across the hand will become even finer, enabling more lifelike feedback.

“We hope to integrate the results of these two studies into our robotics systems, where we have already shown that even simple stimulation strategies can improve people’s abilities to control robotic arms with their brains,” said co-author Robert Gaunt, PhD, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and lead of the stimulation work at the University of Pittsburgh.

Greenspon emphasized that the motivation behind this work is to enhance independence and quality of life for people living with limb loss or paralysis.

“We all care about the people in our lives who get injured and lose the use of a limb — this research is for them,” he said. “This is how we restore touch to people. It’s the forefront of restorative neurotechnology, and we’re working to expand the approach to other regions of the brain.”

The approach also holds promise for people with other types of sensory loss. In fact, the group has also collaborated with surgeons and obstetricians at UChicago on the Bionic Breast Project, which aims to produce an implantable device that can restore the sense of touch after mastectomy.

Although many challenges remain, these latest studies offer evidence that the path to restoring touch is becoming clearer. With each new set of findings, researchers come closer to a future in which a prosthetic body part is not just a functional tool, but a way to experience the world.

“Evoking stable and precise tactile sensations via multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation of the somatosensory cortex” was published in Nature Biomedical Engineering in December 2024. Authors include Charles M. Greenspon, Giacomo Valle, Natalya D. Shelchkova, Thierri Callier, Ev I. Berger-Wolf, Elizaveta V. Okorokova, Efe Dogruoz, Anton R. Sobinov, Patrick M. Jordan, Emily E. Fitzgerald, Dillan Prasad, Ashley Van Driesche, Qinpu He, David Satzer, Peter C. Warnke, John E. Downey, Nicholas G. Hatsopoulos and Sliman J. Bensmaia from the University of Chicago; Taylor G. Hobbs, Ceci Verbaarschot, Jeffrey M. Weiss, Fang Liu, Jorge Gonzalez-Martinez, Michael L. Boninger, Jennifer L. Collinger and Robert A. Gaunt from the University of Pittsburgh; Brianna C. Hutchison, Robert F. Kirsch, Jonathan P. Miller, Abidemi B. Ajiboye, Emily L. Graczyk, from Case Western Reserve University; Lee E. Miller from Northwestern University; and Ray C. Lee from Schwab Rehabilitation Hospital.

“Tactile edges and motion via patterned microstimulation of the human somatosensory cortex” was published in Science in January 2025. Authors include Giacomo Valle, now at Chalmers University in Sweden; Ali H. Alamri, John E. Downey, Patrick M. Jordan, Anton R. Sobinov, Linnea J. Endsley, Dillan Prasad, Peter C. Warnke, Nicholas G. Hatsopoulos, Charles M. Greenspon and Sliman J. Bensmaia from the University of Chicago; Robin Lienkämper, Michael L. Boninger, Jennifer L. Collinger and Robert A. Gaunt from the University of Pittsburgh; and Lee E. Miller from Northwestern University.

END

Fine-tuned brain-computer interface makes prosthetic limbs feel more real

Two new papers document progress in neuroprosthetic technology that lets people feel the shape and movement of objects moving over the "skin" of a bionic hand

2025-01-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

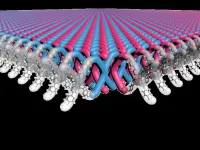

New chainmail-like material could be the future of armor

2025-01-16

EVANSTON, Il. --- In a remarkable feat of chemistry, a Northwestern University-led research team has developed the first two-dimensional (2D) mechanically interlocked material.

Resembling the interlocking links in chainmail, the nanoscale material exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength. With further work, it holds promise for use in high-performance, light-weight body armor and other uses that demand lightweight, flexible and tough materials.

Publishing on Friday (Jan. 17) in the journal ...

The megadroughts are upon us

2025-01-16

Increasingly common since 1980, persistent multi-year droughts will continue to advance with the warming climate, warns a study from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research (WSL), with Professor Francesca Pellicciotti from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) participating. This publicly available forty-year global quantitative inventory, now published in Science, seeks to inform policy regarding the environmental impact of human-induced climate change. It also detected previously ‘overlooked’ events.

Fifteen years of a persistent, devastating megadrought—the longest lasting in a thousand years—have nearly dried out ...

Eavesdropping on organs: Immune system controls blood sugar levels

2025-01-16

When we think about the immune system, we usually associate it with fighting infections. However, a study published in Science by the Champalimaud Foundation reveals a surprising new role. During periods of low energy—such as intermittent fasting or exercise—immune cells step in to regulate blood sugar levels, acting as the “postman” in a previously unknown three-way conversation between the nervous, immune and hormonal systems. These findings open up new approaches for managing conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cancer.

Rethinking the Immune ...

Quantum engineers ‘squeeze’ laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors

2025-01-16

The trick to creating a better quantum sensor? Just give it a little squeeze.

For the first time ever, scientists have used a technique called “quantum squeezing” to improve the gas sensing performance of devices known as optical frequency comb lasers. These ultra-precise sensors are like fingerprint scanners for molecules of gas. Scientists have used them to spot methane leaks in the air above oil and gas operations and signs of COVID-19 infections in breath samples from humans.

Now, in a series of lab experiments, researchers have laid out a path for making those kinds of measurements even more sensitive and faster—doubling the speed of ...

New study reveals how climate change may alter hydrology of grassland ecosystems

2025-01-16

New research co-led by the University of Maryland reveals that drought and increased temperatures in a CO2-rich climate can dramatically alter how grasslands use and move water. The study provides the first experimental demonstration of the potential impacts of climate change on water movement through grassland ecosystems, which make up nearly 40% of Earth’s land area and play a critical role in Earth’s water cycle. The study appears in the January 17, 2025, issue of the journal Science.

“If we want to predict the effects of climate change ...

Polymer research shows potential replacement for common superglues with a reusable and biodegradable alternative

2025-01-16

EMBARGO: THIST CONTENT IS UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 2 PM U.S. EASTERN STANDARD TIME ON JANUARY 16, 2025. INTERESTED MEDIA MAY RECIVE A PREVIEW COPY OF THE JOURNAL ARTICLE IN ADVANCE OF THAT DATE OR CONDUCT INTERVIEWS, BUT THE INFORMATION MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, OR POSTED ONLINE UNTIL AFTER THE RELEASE WINDOW.

Researchers at Colorado State University and their partners have developed an adhesive polymer that is stronger than current commercially available options while also being biodegradable ...

Research team receives $1.5 million to study neurological disorders linked to long COVID

2025-01-16

The National Institute of Mental Health has awarded a significant grant of $1.5 million to Jianyang Du, PhD, of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, for a research study aimed at uncovering the cellular and molecular mechanisms that lead to neurological disorders caused by long COVID-19.

Dr. Du is an associate professor at the College of Medicine in the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology. Colleen Jonsson, PhD, director of the UT Health Science Center Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and professor in the Department of Microbiology, is co-investigator on the grant, and Kun Li, PhD, assistant ...

Research using non-toxic bacteria to fight high-mortality cancers prepares for clinical trials

2025-01-16

A University of Massachusetts Amherst-Ernest Pharmaceuticals team of scientists has made “exciting,” patient-friendly advances in developing a non-toxic bacterial therapy, BacID, to deliver cancer-fighting drugs directly into tumors. This emerging technology holds promise for very safe and more effective treatment of cancers with high mortality rates, including liver, ovarian and metastatic breast cancer.

Clinical trials with participating cancer patients are estimated to begin in 2027. “This is exciting because we now have all the critical pieces for getting an effective bacterial ...

Do parents really have a favorite child? Here’s what new research says

2025-01-16

Siblings share a unique bond built from shared memories, family rituals and the occasional argument. But ask almost anyone with a brother or sister and you’ll likely find a longstanding debate: who’s the favorite? New research from BYU sheds some light on that playful rivalry, revealing how parents might subtly show favoritism based on birth order, personality and gender.

The study, conducted by BYU School of Family Life professor Alex Jensen, found that younger siblings generally receive more favorable ...

Mussel bed surveyed before World War II still thriving

2025-01-16

A mussel bed along Northern California’s Dillon Beach is as healthy and biodiverse as it was about 80 years ago, when two young students surveyed it shortly before Pearl Harbor was attacked and one was sent to fight in World War II.

Their unpublished, typewritten manuscript sat in the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory’s library for years until UC Davis scientists found it and decided to resurvey the exact same mussel bed with the old paper’s meticulous photos and maps directing their way.

The new findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, document ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

SwRI grows capacity to support manufacture of antidotes to combat nerve agent, pesticide exposure in the U.S.

[Press-News.org] Fine-tuned brain-computer interface makes prosthetic limbs feel more realTwo new papers document progress in neuroprosthetic technology that lets people feel the shape and movement of objects moving over the "skin" of a bionic hand