(Press-News.org) Cultural traits — the information, beliefs, behaviors, customs, and practices that shape the character of a population — are influenced by conformity, the tendency to align with others, or anti-conformity, the choice to deliberately diverge. A new way to model this dynamic interplay could ultimately help explain societal phenomena like political polarization, cultural trends, and the spread of misinformation.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences outlines this novel approach. Presenting a mathematical model, SFI Complexity Postdoctoral Fellow Kaleda Denton with colleagues at Stanford University — former SFI Post-baccalaureate Fellow Elisa Heinrich Mora, SFI External Professor Marcus Feldman, and Michael Palmer — expand on previous research to offer a more realistic representation of how conformist and anti-conformist biases shape the transmission of cultural traits through a population.

“The idea behind this research was to come up with a better way to mathematically represent how individuals make decisions in the real world,” says Denton. “If we can do that, we can then scale things up to see what would happen in a population of 10,000 people over the long run.”

Traditional models of conformity often assume individuals gravitate toward the average or “mean” trait in a population. This concept works well if the most popular traits are near this mean, which may be the case for, say, working hours or food portion sizes. However, the mean is a poor indicator of popularity in other cases; for example, if most people fall on either the far left or far right of a political spectrum, but the mean lies in the center.

To address this gap, the authors designed a model that incorporates trait clustering. In this model, individuals conform by adopting traits that are more clustered together (e.g., variations of a far-left political belief) rather than the mean trait in the population (e.g., the centrist view). Anti-conformists, on the other hand, deliberately distance themselves from the traits of their peers, creating polarization.

Using computer simulations, the team analyzed how traits spread across populations over multiple generations. Conformity often led to groups clustering around specific traits, but not necessarily the average. Anti-conformity created a starkly different pattern: a U-shaped distribution, with individuals clustering at the extremes and leaving the middle sparsely populated.

One significant finding was that populations rarely converge to a single trait unless the unrealistic assumption of perfect behavioral copying is imposed. Instead, even small variations in how individuals interpret or adopt traits result in persistent diversity.

“These outcomes align with what we observe in the real world, where cultural practices and ideologies don’t simply average out but instead maintain significant variation,” Denton says.

The research also challenges the notion that conformity always leads to homogeneity. The model shows that under certain conditions, conformity can sustain diversity, while anti-conformity amplifies polarization.

Denton sees broad implications for the study. “This framework could help explain voting behavior, social media trends, or even how people estimate values in group settings,” she says. “It offers a way to understand how individual decisions aggregate into societal patterns, whether that’s consensus-building or polarization.” This model can be tested on real-world data in future studies.

“We’re excited to see if this framework works in different scenarios,” Denton said. “The ultimate goal is to understand how individual choices influence entire populations over time.

END

New study offers insights into how populations conform or go against the crowd

2025-01-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

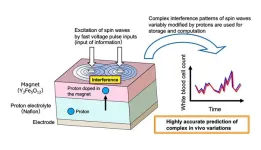

Development of a high-performance AI device utilizing ion-controlled spin wave interference in magnetic materials

2025-01-17

A research team from NIMS and the Japan Fine Ceramics Center (JFCC) has developed a next-generation AI device—a hardware component for AI systems—that incorporates an iono-magnonic reservoir. This reservoir controls spin waves (collective excitations of electron spins in magnetic materials), ion dynamics and their interactions. The technology demonstrated significantly higher information processing performance than conventional physical reservoir computing devices, underscoring its potential to transform AI technologies.

As AI devices become increasingly sophisticated, ...

WashU researchers map individual brain dynamics

2025-01-17

By Shawn Ballard

The complexity of the human brain – 86 billion neurons strong with more than 100 trillion connections – enables abstract thinking, language acquisition, advanced reasoning and problem-solving, and the capacity for creativity and social interaction. Understanding how differences in brain signaling and dynamics produce unique cognition and behavior in individuals has long been a goal of neuroscience research, yet many phenomena remain unexplained.

A study from neuroscientists and ...

Technology for oxidizing atmospheric methane won’t help the climate

2025-01-17

As the atmosphere continues to fill with greenhouse gases from human activities, many proposals have surfaced to “geoengineer” climate-saving solutions, that is, alter the atmosphere at a global scale to either reduce the concentrations of carbon or mute its warming effect.

One recent proposal seeks to infuse the atmosphere with hydrogen peroxide, insisting that it would both oxidize methane (CH4), an extremely potent greenhouse gas while improving air quality.

Too good to be true?

University of Utah atmospheric scientists Alfred Mayhew and Jessica Haskins were skeptical, so they set out to test the claims behind this proposal. Their results, published on ...

US Department of Energy announces Early Career Research Program for FY 2025

2025-01-17

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced it is accepting applications for the 2025 DOE Office of Science Early Career Research Program to support the research of outstanding scientists early in their careers. The program will support over 80 early career researchers for five years at U.S. academic institutions, DOE national laboratories, and Office of Science user facilities.

“The vision, creativity, and effort of early career faculty drive innovation in the basic science enterprise. The Department of Energy’s Office of Science is dedicated to ...

PECASE winners: 3 UVA engineering professors receive presidential early career awards

2025-01-17

University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science faculty members James T. Burns, Coleen Carrigan and Liheng Cai received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) on Tuesday, as did two UVA Engineering alumni, Ashutosh Giri and Ryan Johnson.

PECASE is the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding scientists and engineers early in their careers. According to the release from the White House, this award recognizes “innovative and far-reaching developments in science and technology.”

“This award year has been extraordinary not ...

‘Turn on the lights’: DAVD display helps navy divers navigate undersea conditions

2025-01-17

ARLINGTON, Va.—A favorite childhood memory for Dr. Sandra Chapman was visiting the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor with her father. They hung out at the memorial so often that they memorized lines to the movie playing prior to the boat ride to the memorial.

So it’s appropriate that Chapman — a program officer in the Office of Naval Research’s (ONR) Warfighter Performance Department — is passionate about her involvement in the development of an innovative technology recently applied to efforts to preserve the area around the USS Arizona ...

MSU researcher’s breakthrough model sheds light on solar storms and space weather

2025-01-17

Images

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Our sun is essentially a searing hot sphere of gas. Its mix of primarily hydrogen and helium can reach temperatures between 10,000 and 3.6 million degrees Fahrenheit on its surface and its atmosphere’s outermost layer. Because of that heat, the blazing orb constantly oozes a stream of plasma, made up of charged subatomic particles — mainly protons and electrons. The sun’s gravity can’t contain them because they hold so much energy as heat, so they drift away into space as solar wind. Understanding how charged particles ...

Nebraska psychology professor recognized with Presidential Early Career Award

2025-01-17

Maital Neta, professor of psychology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, has received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding scientists and engineers early in their careers.

Neta, Carl A. Happold Professor of Psychology, directs the Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Lab and is resident faculty of the Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior.

Neta said she was “very grateful” for the honor, announced ...

New data shows how ‘rage giving’ boosted immigrant-serving nonprofits during the first Trump Administration

2025-01-17

As Donald Trump prepares to take office for a second term as President, research led by the University of California, Santa Cruz is demonstrating the important role nonprofits played during Trump’s first term as a counterforce that channeled public resistance to anti-immigrant policies.

The new study, published in the journal International Migration Review, shows how nonprofits that provide legal services for immigrants ended up receiving increases in public contributions in the wake of Trump's attacks on immigrants.

Previously, there had been many reported examples of this backlash effect, sometimes called ...

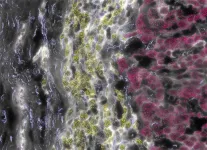

Unique characteristics of a rare liver cancer identified as clinical trial of new treatment begins

2025-01-17

Like many rare diseases, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FLC) mounts a ferocious attack against an unlucky few—in this case, children, adolescents, and young adults. Because its symptoms can vary from person to person, it’s often missed or misdiagnosed until it has metastasized and becomes lethal. Moreover, drug therapies for common liver cancers are not just useless for FLC patients but actually harmful.

But new insights about the disease, coupled with a just-launched clinical trial of a promising drug treatment, could significantly improve health outcomes. Researchers in Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Cellular Biophysics, headed by Sanford ...