U of Alberta researcher working towards pharmacological targets for cholera

2011-01-21

(Press-News.org) Just over a year after the earthquake in Haiti killed 222,000 people there's a new problem that is killing Haitians. A cholera outbreak has doctors in the area scrambling and the water-borne illness has already claimed 3600 lives according to officials with Médicin Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders).

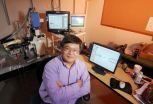

Stefan Pukatzki, a bacteriologist in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry at the University of Alberta, is hoping that down the road he can help prevent deadly cholera outbreaks.

His lab studies Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria that makes up the disease, and he has discovered how it infects and kills other bacteria and host cells. This discovery, published in November's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could explain how this organism survives between epidemics. Pukatzki says Vibrio cholerae lives in fresh water mix between epidemics and no one has known how it competed and survived with other bacteria in the water.

A better understanding of how this organism infects cells means Pukatzki may be able to devise novel strategies to block the function.

Pukatzki discovered that Vibrio cholerae uses molecular nano-syringes to puncture host cells and secrete toxins straight in to the other organism; this is called the type six secretion system.

"Vibrio cholerae uses these syringes so when it comes in contact with another bacteria, like E. coli, which is a gut bacterium, it kills it," said Pukatzki. "That's a novel phenomenon. We knew it [Vibrio cholerae] competed with cells of the immune system but we didn't know it was able to kill other bacteria.

"Keep in mind these syringes are sitting on the outside of the bacterium so they make good vaccine targets," said Pukatzki. "That's actually better because you could either inhibit the type six function or you could induce an immune response with these components that are sitting on the outside."

Pukatzki is excited because the type six secretion system isn't unique to Vibrio cholera; it is found in most major pathogens.

"We really think that even though this pathway is important for cholera, I think that whatever we find we can apply to other diseases as well because they're so highly conserved," said Pukatzki.

Pukatzki's lab is now looking to get a better understanding of this mechanism and continue working towards a potential pharmaceutical target.

INFORMATION:

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011-01-21

Mutations in a gene called INF2 are by far the most common cause of a dominantly inherited condition that leads to kidney failure, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society Nephrology (JASN). The results may help with screening, prevention, and therapy.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) attacks the kidney's filtering system and causes serious scarring. Approximately 20,000 persons are currently living with kidney failure due to FSGS in the United States, with an associated annual cost of more than $3 billion. In ...

2011-01-21

Routine mammograms performed for breast cancer screening could serve another purpose as well: detecting calcifications in the blood vessels of patients with advanced kidney disease, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN).

Mammograms show calcium deposits in the breast arteries in nearly two-thirds of women with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), according to the study by W. Charles O'Neill, MD (Emory University, Atlanta). "Breast arterial calcification is a specific and useful marker of medial ...

2011-01-21

Athens, Ga. – It's a common assumption that animal migration, like human travel across the globe, can transport pathogens long distances, in some cases increasing disease risks to humans. West Nile Virus, for example, spread rapidly along the East coast of the U.S., most likely due to the movements of migratory birds. But in a paper just published in the journal Science, researchers in the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology report that in some cases, animal migrations could actually help reduce the spread and prevalence of disease and may even promote the evolution ...

2011-01-21

In a new paper published Jan. 21 in the journal Science, a team of researchers led by Microbiology and Immunology professor Blossom Damania, PhD, has shown for the first time that the Kaposi sarcoma virus has a decoy protein that impedes a key molecule involved in the human immune response.

The work was performed in collaboration with W.R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor, Jenny Ting, PhD. First author, Sean Gregory, MS, a graduate student in UNC's Department of Microbiology and Immunology played a critical role in this work.

The virus-produced protein, called ...

2011-01-21

VIDEO:

This video shows the micropipette adhesion frequency assay used to study the mechanical interactions between a T cell and an antigen presented on a red blood cell.

Click here for more information.

Researchers have for the first time mapped the complex choreography used by the immune system's T cells to recognize pathogens while avoiding attacks on the body's own cells.

The researchers found that T cell receptors – molecules located on the surface of the T cell ...

2011-01-21

The discovery of an ancient fossil, nicknamed 'Mrs T', has allowed scientists for the first time to sex pterodactyls – flying reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs between 220-65 million years ago.

Pterodactyls featured prominently in Spielberg's Jurassic Park III and are a classic feature of many dinosaur movies where they are often depicted as giant flying reptiles with a crest.

The discovery of a flying reptile fossilised together with an egg in Jurassic rocks (about 160 million years old) in China provides the first direct evidence for gender in these extinct ...

2011-01-21

In 2008, an international team of scientists studying an exotic new superconductor based on the element ytterbium reported that it displays unusual properties that could change how scientists understand and create materials for superconductors and the electronics used in computing and data storage.

But a key characteristic that explains the material's unusual properties remained tantalizingly out of reach in spite of the scientists' rigorous battery of experiments and exacting measurements. So members of that team from the University of Tokyo reached out to theoretical ...

2011-01-21

Scientists from the University of Leeds have made a fundamental step in the search for therapies for amyloid-related diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and diabetes mellitus. By pin-pointing the reaction that kick-starts the formation of amyloid fibres, scientists can now seek to further understand how these fibrils develop and cause disease.

Amyloid fibres, which are implicated in a wide range of diseases, form when proteins misfold and stick together in long, rope-like structures. Until now the nature of the first misfold, which then causes a chain reaction of ...

2011-01-21

The anti-diuretic hormone "vasopressin" is released from the brain, and known to work in the kidney, suppressing the diuresis. Here, the Japanese research team led by Professor Yasunobu OKADA, Director-General of National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), and Ms. Kaori SATO, a graduate student of The Graduate University for Advanced Studies, clarified the novel function of "vasopressin" that works in the brain, as well as in the kidney via the same type of the vasopressin receptor, to maintain the size of the vasopressin neurons. It might be a useful result for ...

2011-01-21

Humans use their senses to help keep track of short intervals of time according to new research, which suggests that our perception of time is not maintained by an internal body clock alone.

Scientists from UCL (University College London) set out to answer the question "Where does our sense of time come from?" Their results show that it comes partly from observing how much the world changes, as we have learnt to expect our sensory inputs to change at a particular 'average' rate. Comparing the change we see to this average value helps us judge how much time has passed, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] U of Alberta researcher working towards pharmacological targets for cholera