Scientists simulate asteroid collision effects on climate and plants

2025-02-05

(Press-News.org)

A new climate modeling study published in the journal Science Advances by researchers from the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) at Pusan National University in South Korea presents a new scenario of how climate and life on our planet would change in response to a potential future strike of a medium-sized (~500 m) asteroid.

The solar system is full of objects with near-Earth orbits. Most of them do not pose any threat to Earth, but some of them have been identified as objects of interest with non-negligible collision probabilities. Among them is the asteroid Bennu with a diameter of about 500 m, which, according to recent studies [Farnocchia et al. 2021], has an estimated chance of 1-in-2700 of colliding with Earth in September 2182. This is similar to the probability of flipping a coin 11 times in a row with the same outcome.

To determine the potential impacts of an asteroid strike on our climate system and on terrestrial plants and plankton in the ocean, researchers from the ICCP set out to simulate an idealized collision scenario with a medium-sized asteroid using a state-of-the-art climate model. The effect of the collision is represented by a massive injection of several hundred million tons of dust into the upper atmosphere. Unlike previous studies, the new research also simulates terrestrial and marine ecosystems, as well as the complex chemical reactions in the atmosphere.

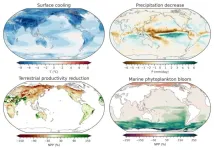

Using the IBS supercomputer Aleph, the researchers ran several dust impact scenarios for a Bennu-type asteroid collision with Earth. In response to dust injections of 100–400 million tons, the supercomputer model simulations show dramatic disruptions in climate, atmospheric chemistry, and global photosynthesis in the 3–4 years following the impact (Figure 1). For the most intense scenario, solar dimming due to dust would cause global surface cooling of up to 4˚C, a reduction of global mean rainfall by 15%, and severe ozone depletion of about 32%. However, regionally, these impacts could be much pronounced.

“The abrupt impact winter would provide unfavorable climate conditions for plants to grow, leading to an initial 20–30% reduction of photosynthesis in terrestrial and marine ecosystems. This would likely cause massive disruptions in global food security,” says Dr. Lan DAI, postdoctoral research fellow at the ICCP and lead author of the study.

When the researchers looked into ocean model data from their simulations, they were surprised to find that plankton growth displayed a completely different behaviour. Instead of the rapid reduction and slow two-year-long recovery on land, plankton in the ocean recovered already within 6 months and even increased afterwards to levels not even seen under normal climate conditions.

“We were able to track this unexpected response to the iron concentration in the dust,” says Prof. Axel TIMMERMANN, Director of the ICCP and co-author of the study. Iron is a key nutrient for algae, but in some areas, such as the Southern Ocean and the eastern tropical Pacific, its natural abundance is very low. Depending on the iron content of the asteroid and of the terrestrial material, that is blasted into the stratosphere, the otherwise nutrient-depleted regions can become nutrient-enriched with bioavailable iron, which in turn triggers unprecedented algae blooms. According to the computer simulations, the post-collision increase of marine productivity would be most pronounced for silicate-rich algae—referred to as diatoms. Their blooms would also attract large amounts of zooplankton—small predators, which feed on the diatoms.

“The simulated excessive phytoplankton and zooplankton blooms might be a blessing for the biosphere and may help alleviate emerging food insecurity related to the longer-lasting reduction in terrestrial productivity,” adds Dr. Lan DAI.

“On average, medium-sized asteroids collide with Earth about every 100–200 thousand years. This means that our early human ancestors may have experienced some of these planet-shifting events before with potential impacts on human evolution and even our own genetic makeup,” says Prof. Timmermann.

The new study in Science Advances provides new insights into the climatic and biospheric responses to collisions with near-Earth orbit objects. In the next step the ICCP researchers from South Korea plan to study early human responses to such events in more detail by using agent-based computer models, which simulate individual humans, their life cycles and their search for food.

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2025-02-05

PHILADELPHIA — (February 5, 2025) —The lab of The Wistar Institute’s Jessie Villanueva, Ph.D., has identified a new strategy for attacking treatment-resistant melanoma: inhibiting the gene S6K2. The team published their findings in the paper, “Selective abrogation of S6K2 identifies lipid homeostasis as a survival vulnerability in MAPKi-resistant NRASMUT melanoma,” from the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“This work shows that, even in the face of notoriously ...

2025-02-05

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Fool me once, shame on you. Fool myself, and I may end up feeling smarter, according to a new study led by Sara Dommer, assistant professor of marketing at Penn State.

Dommer wondered why people cheat on tasks like completing crossword puzzles or Wordle and counting calories when the rewards are purely intrinsic, like feeling smarter or healthier. She found that when cheating offers the opportunity to improve self-perception, individuals engage in diagnostic self-deception — that is, they cheat yet deceive themselves by attributing their heightened performance to their innate ability instead ...

2025-02-05

A new study led by researchers from Peking University, published in Health Data Science, reveals a sharp rise in the burden of early-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D) among adolescents and young adults in China from 1990 to 2021. Despite improvements in mortality rates, the incidence and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) associated with the disease have grown alarmingly.

Using data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021, the study shows that the age-standardized incidence rate nearly doubled, increasing from 140.20 per 100,000 in 1990 to 315.97 per 100,000 in 2021, with an average annual percentage change ...

2025-02-05

NEW YORK, NY (Feb. 5, 2025)--Columbia scientists have found specialized neurons in the brains of mice that order the animals to stop eating.

Though many feeding circuits in the brain are known to play a role in monitoring food intake, the neurons in those circuits do not make the final decision to cease eating a meal.

The neurons identified by the Columbia scientists, a new element of these circuits, are located in the brainstem, the oldest part of the vertebrate brain. Their discovery could lead ...

2025-02-05

About The Study: The results of this cluster trial demonstrate that salt substitution was safe, along with reduced risks of stroke recurrence and death, which underscores large health gains from scaling up this low-cost intervention among patients with stroke.

Corresponding Authors: To contact the corresponding authors, email Lijing L. Yan, MPH, PhD, (lijing.yan@duke.edu) and Maoyi Tian, PhD, (maoyi.tian@hrbmu.edu.cn)

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2024.5417)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...

2025-02-05

About The Study: This study found that most publicly targeted fatal mass shootings involved multiple types of firearms and handguns were the most common type of firearm present. Assault weapons being present during a publicly targeted mass shooting was associated with a slight increase in the number of injuries and deaths occurring during that incident.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Leslie M. Barnard, MPH, DrPH, email leslie.barnard@ucdenver.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.58085)

Editor’s ...

2025-02-05

About The Study: Drug overdose deaths have increased exponentially since 1979. This rate of increase accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic but has since waned. When comparing recent drug-related mortality rates with their pre-2020 trajectory, the vast majority of states remained higher than expected. In the 4 years between 2020 and 2023, nearly all states had higher drug-related mortality rates than their 2019 rates.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Keith Humphreys, ...

2025-02-05

University of Cincinnati experts will present research at the International Stroke Conference 2025 in Los Angeles.

Study finds small number of patients eligible for new ICH treatment

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), when there is bleeding into brain tissue from the rupture of a damaged blood vessel, is one of the most devastating types of stroke. Patients often suffer from severe neurologic disability or even death. There were no proven treatments for patients with ICH until recently.

“We now have one ...

2025-02-05

Superconducting materials are similar to the carpool lane in a congested interstate. Like commuters who ride together, electrons that pair up can bypass the regular traffic, moving through the material with zero friction.

But just as with carpools, how easily electron pairs can flow depends on a number of conditions, including the density of pairs that are moving through the material. This “superfluid stiffness,” or the ease with which a current of electron pairs can flow, is a key measure of a material’s superconductivity.

Physicists at MIT and Harvard University have now directly measured superfluid stiffness for the first time ...

2025-02-05

In India, many kids who work in retail markets have good math skills: They can quickly perform a range of calculations to complete transactions. But as a new study shows, these kids often perform much worse on the same kinds of problems as they are taught in the classroom. This happens even though many of these students still attend school or attended school through 7th or 8th grades.

Conversely, the study also finds, Indian students who are still enrolled in school and don’t have jobs do better on school-type math problems, but they often fare poorly at the kinds of problems that occur in marketplaces.

Overall, both the “market kids” and the “school kids” ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists simulate asteroid collision effects on climate and plants