(Press-News.org)

Embargoed for release: Thursday, February 6, 2025, 2:00 PM ET

Key points:

Comprehensive genetic mapping of Plasmodium knowlesi, a zoonotic parasite that causes malaria, has revealed the genes required for malaria infection of the blood, and those driving drug resistance.

By identifying specific druggable targets and determinants of resistance, the map provides insights that could help the development of new therapeutics.

Boston, MA—A new, comprehensive map of all the genes essential for blood infections in Plasmodium knowlesi (P. knowlesi), a parasite that causes malaria in humans, has been generated by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and colleagues. The map contains the most complete classification of essential genes in any Plasmodiumspecies and can be used to identify druggable parasite targets and mechanisms of drug resistance that can inform the development of new treatments for malaria.

“We hope that our findings are a major step for the field of malaria research and control,” said co-corresponding author Manoj Duraisingh, John LaPorte Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. “Emerging drug resistance to the small number of antimalarial drugs is a growing problem. This map will be an invaluable resource to help researchers combat one of the leading causes of infectious disease death around the world.”

The study will be published Feb. 6, 2025, in Science.

Each year, around 249 million human cases of malaria are caused by a Plasmodium species, resulting in about 608,000 deaths. P. knowlesi is one of several species responsible for human malaria. It is a zoonotic parasite that can be lethal and is an emerging public health problem in Southeast Asia.

The researchers developed a powerful genetic approach in P. knowlesi, known as transposon mutagenesis, to disrupt all of the genes not needed for growth in human red blood cells, thus revealing a map of all of those remaining that were essential for growth. This identified at a genomic scale the molecular requirements for parasites to grow. The researchers were also able to pinpoint specific genes that cause resistance to current antimalarials.

“Knowing all of the essential genes in P. knowlesi allows us to understand the molecular strategies that the parasite takes to grow, to respond to environmental changes, and to respond to therapeutics such as antimalarials,” said co-first author Sheena Dass, postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. “This molecular blueprint will help malaria researchers in the design and execution of biological studies of malaria as well as inform strategies to monitor and limit the emergence of drug resistance.”

The researchers noted that the findings also provide insights into one other malaria-causing Plasmodium species, P. vivax, due to their evolutionary relatedness. P. vivax, which is poorly studied because it is not culturable or genetically tractable, is a major challenge to elimination efforts.

Brendan Elsworth and Sida Ye were co-first authors. Co-corresponding author was Kourosh Zarringhalam at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Other Harvard Chan co-authors included Jacob Tennessen, Basil Thommen, Aditya Paul, Usheer Kanjee, and Christof Grüring.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants 5R01AI168163, 5R01 AI167570, ORIP/OD P51OD011132, and U42 PDP11023); the Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoc Mobility (fellowships PBSKP3_140144 and P300P3_151146); and the Food and Drug Administration Intramural Research Program.

“The essential genome of Plasmodium knowlesi reveals determinants of antimalarial susceptibility,” Brendan Elsworth, Sida Ye, Sheena Dass, Jacob A. Tennessen, Qudseen Sultana, Basil T. Thommen, Aditya S. Paul, Usheer Kanjee, Christof Grüring, Marcelo U. Ferreira, Marc-Jan Gubbels, Kourosh Zarringhalam, Manoj T. Duraisingh, Science, February 7, 2025, doi: 10.1126/science.adq6241

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news and events from our Studio.

###

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is a community of innovative scientists, practitioners, educators, and students dedicated to improving health and advancing equity so all people can thrive. We research the many factors influencing health and collaborate widely to translate those insights into policies, programs, and practices that prevent disease and promote well-being for people around the world. We also educate thousands of public health leaders a year through our degree programs, postdoctoral training, fellowships, and continuing education courses. Founded in 1913 as America’s first professional training program in public health, the School continues to have an extraordinary impact in fields ranging from infectious disease to environmental justice to health systems and beyond.

END

In brief:

• In Greenland, an international team of researchers led by ETH Zurich has discovered that countless tiny ice quakes take place deep inside ice streams.

• These quakes are responsible for the fact that ice streams also move with a continuous stick-slip motion and not only like viscous honey as previously considered.

• The researchers recorded seismic data from inside the ice stream using a fibre-optic cable in a 2,700-metre deep borehole.

The ...

Whale song can be as efficient as – and, in some cases, more efficient than – human communication, according to a new study in Science Advances. Meanwhile, new unrelated research in Science further investigates whale song’s adherence to a universal linguistic law, as observed in recordings of humpback whales.

Natural selection favors the pithy over the longwinded. For example, yelling “Duck!” is faster and far more effective than shouting “Be careful, there is an incoming projectile, and you need to move out of the way!” ...

Researchers have uncovered a neural mechanism in the brains of mice that enables them to override instinctive fear responses; dysfunction in this mechanism may contribute to inappropriate or excessive fear responses, they say. According to the findings, targeting these circuits could offer new therapeutic avenues for treating fear-related disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety. Fear responses to visual threats, such as escaping from an approaching predator, are critical instinctive reactions for survival and are ...

The hormone adrenomedullin disrupts insulin signaling in blood vessel cells, contributing to systemic insulin resistance in obesity-associated type 2 diabetes, according to a new study. Blocking adrenomedullin’s effects restores insulin function and improves glucose control in a mouse model, suggesting a potential new target for treating obesity-related metabolic disease. Diabetes is a leading global cause of illness, mortality, and healthcare expenditures, with most cases stemming from obesity-induced insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Insulin resistance primarily ...

In this Special Issue of Science, 3 Reviews and a Policy Forum highlight research on Earth’s frozen places – from the Arctic to the Antarctic – and how it’s changing due to climate change and the geopolitical challenges this important work faces. In the first Review, Julienne Stroeve and colleagues provide a preview of what the Arctic region may look like in a warmer world. Without stronger climate action, global temperatures are set to rise +2.7°C above preindustrial levels, ...

Researchers at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC) at UCL have unveiled the precise brain mechanisms that enable animals to overcome instinctive fears. Published today in Science, the study in mice could have implications for developing therapeutics for fear-related disorders such as phobias, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The research team, led by Dr Sara Mederos and Professor Sonja Hofer, mapped out how the brain learns to suppress responses to perceived threats that prove ...

Known for their powerful punch, mantis shrimp can smash a shell with the force of a .22 caliber bullet. Yet, amazingly, these tough critters remain intact despite the intense shockwaves created by their own strikes.

Northwestern University researchers have discovered how mantis shrimp remain impervious to their own punches. Their fists, or dactyl clubs, are covered in layered patterns, which selectively filter out sound. By blocking specific vibrations, the patterns act like a shield against self-generated shockwaves.

The study will be published on Friday (Feb. 7) in the journal Science.

The findings someday could be applied to developing ...

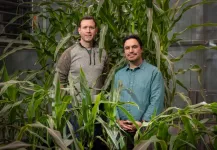

A corn plant knows how to find water in soil with the very tips of its roots, but some varieties, including many used for breeding high-yielding corn in the U.S., appear to have lost a portion of that ability, according to a Stanford-led study. With climate change increasing droughts, the findings hold potential for developing more resilient varieties of corn.

The study, published in the journal Science, uncovers genetic mechanisms behind root “hydropatterning,” or how plant roots branch toward water and avoid dry spaces in soil. In particular, the researchers ...

Humpback whale song is a striking example of a complex, culturally transmitted behavior, but up to now, there was little evidence it has language-like structure. Human language, which is also culturally transmitted, has recurring parts whose frequency of use follows a particular pattern. In humans, these properties help learning and may come about because they help language be passed from one generation to the next. This work innovatively applies methods inspired by how babies discover words in speech to humpback whale recordings, uncovering the same statistical structures found in all human languages. It reveals previously undetected structure in ...

In a groundbreaking study, University of Florida scientists statistically analyzed large amounts of data collected by Burmese python contractors, revealing critical insights about how to most efficiently remove the reptiles.

Researchers correlated survey outcomes, including python removals, with survey conditions, using statistical modeling. For example, the researchers examined if factors like time or temperature impacted the chance of removing a python. They also analyzed whether the most surveyed areas aligned with the highest python removals. This allowed the researchers to ...