(Press-News.org) Take a look around your home and you’ll find yourself surrounded by familiar comforts—photos of family and friends on the wall, well-worn sneakers by the door, a shelf adorned with travel mementos.

Objects like these are etched into our memory, shaping who we are and helping us navigate environments and daily life with ease. But how do these memories form? And what if we could stop them from slipping away under a devastating condition like Alzheimer’s disease?

Scientists at UBC’s faculty of medicine have just uncovered a crucial piece of the puzzle. In a study published today in Nature Communications, the researchers have discovered a new type of brain cell that plays a central role in our ability to remember and recognize objects.

Called ‘ovoid cells,’ these highly-specialized neurons activate each time we encounter something new, triggering a process that stores those objects in memory and allowing us to recognize them months—potentially even years—later.

“Object recognition memory is central to our identity and how we interact with the world,” said Dr. Mark Cembrowski, the study’s senior author, and an associate professor of cellular and physiological sciences at UBC and investigator at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health. “Knowing if an object is familiar or new can determine everything from survival to day-to-day functioning, and has huge implications for memory-related diseases and disorders.”

Hiding in plain sight

Named for the distinct egg-like shape of their cell body, ovoid cells are present in relatively small numbers within the hippocampus of humans, mice and other animals.

Adrienne Kinman, a PhD student in Dr. Cembrowski’s lab and the study’s lead author, discovered the cells’ unique properties while analyzing a mouse brain sample, when she noticed a small cluster of neurons with highly distinctive gene expression.

“They were hiding right there in plain sight,” said Kinman. “And with further analysis, we saw that they are quite distinct from other neurons at a cellular and functional level, and in terms of their neural circuitry.”

To understand the role ovoid cells play, Kinman manipulated the cells in mice so they would glow when active inside the brain. The team then used a miniature single-photon microscope to observe the cells as the mice interacted with their environment.

The ovoid cells lit up when the mice encountered an unfamiliar object, but as they grew used to it, the cells stopped responding. In other words, the cells had done their jobs: the mice now remembered the objects.

"What’s remarkable is how vividly these cells react when exposed to something new. It’s rare to witness such a clear link between cell activity and behaviour," said Kinman. "And in mice, the cells can remember a single encounter with an object for months, which is an extraordinary level of sustained memory for these animals."

New insights for Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy

The researchers are now investigating the role that ovoid cells play in a range of brain disorders. The team’s hypothesis is that when the cells become dysregulated, either too active or not active enough, they could be driving the symptoms of conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy.

“Recognition memory is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease—you forget what keys are, or that photo of a person you love. What if we could manipulate these cells to prevent or reverse that?” said Kinman. “And with epilepsy, we’re seeing that ovoid cells are hyperexcitable and could be playing a role in seizure initiation and propagation, making them a promising target for novel treatments.”

For Dr. Cembrowski, discovering the highly specialized neuron upends decades of conventional thinking that the hippocampus contained only a single type of cell that controlled multiple aspects of memory.

“From a fundamental neuroscience perspective, it really transforms our understanding of how memory works,” he said. “It opens the door to the idea that there may be other undiscovered neuron types within the brain, each with specialized roles in learning, memory and cognition. That creates a world of possibilities that would completely reshape how we approach and treat brain health and disease."

Interview language(s): English

END

Meet the newly discovered brain cell that allows you to remember objects

Discovery of ‘ovoid cells’ reshapes our understanding of how memory works, and could open the door to new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and more

2025-02-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Engineered animals show new way to fight mercury pollution

2025-02-12

Australian scientists have found an effective new way to clean up methylmercury, one of the world’s most dangerous pollutants, which often builds up in our food and environment because of industrial activities such as illegal gold mining and burning coal. The discovery, published in Nature Communications on 12 February 2025, could lead to new ways of engineering animals to protect both wildlife and human health.

The research team from Macquarie University's Applied BioSciences, CSIRO, Macquarie Medical School, and the ARC Centre of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, has successfully genetically modified fruit flies and zebrafish to transform methylmercury into a ...

The 3,000-year coral reef shutdown: a mysterious pause and a remarkable recovery

2025-02-12

New study reveals that coral reefs in the Gulf of Eilat experienced a surprising 3,000-year "shutdown" in growth, from about 4,400 to 1,000 years ago, likely due to a temporary drop in sea level that could have been caused by global cooling. This phenomenon, which aligns with similar reef interruptions in Mexico, Brazil, and Australia, suggests a widespread environmental shift during that period. Despite the long pause, the reef eventually recovered, with coral species reappearing from deeper ...

Worm surface chemistry reveals secrets to their development and survival

2025-02-12

A new study has revealed the clearest-ever picture of the surface chemistry of worm species that provides groundbreaking insights into how animals interact with their environment and each other. These discoveries could pave the way for strategies to deepen our understanding of evolutionary adaptations, refine behavioural research, and ultimately overcome parasitic infections.

Scientists from the University’s School of Pharmacy used an advanced mass spectrometry imaging system to examine the nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans and Pristionchus pacificus, aiming to characterise species-specific surface chemical ...

Splicing twins: unravelling the secrets of the minor spliceosome complex

2025-02-12

In human cells, only a small proportion of the information written in genes is used to produce proteins. How does the cell select this information? A large molecular machine called the spliceosome continuously separates the coding and non-coding regions of our genes – and it's doing this even as you read these lines.

The spliceosome is critical for the proper functioning of every cell, and numerous genetic disorders are linked to problems with spliceosome function. In most eukaryotic cells, two types of ...

500-year-old Transylvanian diaries show how the Little Ice Age completely changed life and death in the region

2025-02-12

Glaciers, sediments, and pollen can be used to reconstruct the climate of the past. Beyond ‘nature’s archive,’, other sources, such as diaries, travel notes, parish or monastery registers, and other written documents – known at the ‘society’s archive’ – contain reports and observations about local climates in bygone centuries.

In contrast, the second half of the century was characterized by heavy rainfall and floods, particularly in the 1590s.

The western parts of the European continent cooled significantly when in the 16th century a period known as the ‘Little Ice Age’ intensified. During the second ...

Overcoming nicotine withdrawal: Clues found in neural mechanisms of the brain

2025-02-12

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 22% of the global population smokes, with more than 9 million smoking-related deaths reported annually. Effective treatments to alleviate nicotine withdrawal symptoms caused by smoking cessation are essential for successful smoking cessation. Currently, approved treatments for nicotine withdrawal include Bupropion and Varenicline, but there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options to improve smoking cessation success rates.

The research team led by Dr. Heh-In Im at the Center for Brain Disorders of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) has identified a novel brain region and neural mechanism ...

Survey: Women prefer female doctors, but finding one for heart health can be difficult

2025-02-12

EMBARGOED UNTIL WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2025

Mountain View, CA (Feb. 12, 2025) – According to the U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard, only about 17% of cardiologists are women, ranking as one of the lowest specialties among female physicians, yet heart disease remains the number one killer of women, accounting for one in five female deaths. El Camino Health is innovating a solution to address the unique symptoms and risk factors of heart disease in women.

A new national survey conducted by El Camino Health found women (59%) are ...

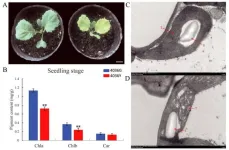

Leaf color mysteries unveiled: the role of BoYgl-2 in cabbage

2025-02-12

A new study has uncovered a novel P-type PPR protein, BoYgl-2, which plays a crucial role in chloroplast RNA editing and chlorophyll biosynthesis in cabbage. This discovery sheds new light on the molecular mechanisms governing leaf color formation and chloroplast development, filling a significant knowledge gap in plant physiology. By identifying a spontaneous yellow-green leaf mutant and deciphering the function of BoYgl-2, the research paves the way for innovative crop breeding strategies that could enhance plant productivity and agricultural sustainability.

Leaf color is more than just an aesthetic trait—it is a vital agronomic characteristic ...

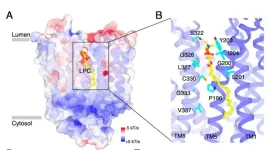

NUS Medicine study: Inability of cells to recycle fats can spell disease

2025-02-12

Accumulation of fat molecules is detrimental to the cell. Researchers from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), have made a breakthrough in understanding how our cells manage to stay healthy by recycling important fat molecules. Their study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reveals how a protein called Spinster homolog 1 (Spns1) helps transport fats out of cell compartments known as lysosomes.

Led by Associate Professor Nguyen Nam Long, from the Department of Biochemistry and Immunology Translational Research Programme (TRP) at NUS Medicine, the team found that Spns1 is like a cellular ...

D2-GCN: a graph convolutional network with dynamic disentanglement for node classification

2025-02-12

Classic Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) often learn node representation holistically, which would ignore the distinct impacts from different neighbors when aggregating their features to update a node's representation. Disentangled GCNs have been proposed to divide each node's representation into several feature channels. However, current disentangling methods do not try to figure out how many inherent factors the model should assign to help extract the best representation of each node.

To solve the problems, a research team led by Chuliang WENG published their new ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The internet names a new deep-sea species, Senckenberg researchers select a scientific name from over 8,000 suggestions.

UT San Antonio-led research team discovers compound in 500-million-year-old fossils, shedding new light on Earth’s carbon cycle

Maternal perinatal depression may increase the risk of autistic-related traits in girls

Study: Blocking a key protein may create novel form of stress in cancer cells and re-sensitize chemo-resistant tumors

HRT via skin is best treatment for low bone density in women whose periods have stopped due to anorexia or exercise, says study

Insilico Medicine showcases at WHX 2026: Connecting the Middle East with global partners to accelerate translational research

From rice fields to fresh air: Transforming agricultural waste into a shield against indoor pollution

University of Houston study offers potential new targets to identify, remediate dyslexia

Scientists uncover hidden role of microalgae in spreading antibiotic resistance in waterways

Turning orange waste into powerful water-cleaning material

Papadelis to lead new pediatric brain research center

Power of tiny molecular 'flycatcher' surprises through disorder

Before crisis strikes — smartwatch tracks triggers for opioid misuse

Statins do not cause the majority of side effects listed in package leaflets

UC Riverside doctoral student awarded prestigious DOE fellowship

UMD team finds E. coli, other pathogens in Potomac River after sewage spill

New vaccine platform promotes rare protective B cells

Apes share human ability to imagine

Major step toward a quantum-secure internet demonstrated over city-scale distance

Increasing toxicity trends impede progress in global pesticide reduction commitments

Methane jump wasn’t just emissions — the atmosphere (temporarily) stopped breaking it down

Flexible governance for biological data is needed to reduce AI’s biosecurity risks

Increasing pesticide toxicity threatens UN goal of global biodiversity protection by 2030

How “invisible” vaccine scaffolding boosts HIV immune response

Study reveals the extent of rare earthquakes in deep layer below Earth’s crust

Boston College scientists help explain why methane spiked in the early 2020s

Penn Nursing study identifies key predictors for chronic opioid use following surgery

KTU researcher’s study: Why Nobel Prize-level materials have yet to reach industry

Research spotlight: Interplay of hormonal contraceptive use, stress and cardiovascular risk in women

Pennington Biomedical’s Dr. Catherine Prater awarded postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association

[Press-News.org] Meet the newly discovered brain cell that allows you to remember objectsDiscovery of ‘ovoid cells’ reshapes our understanding of how memory works, and could open the door to new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and more