(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Humanity may not be extraordinary but rather the natural evolutionary outcome for our planet and likely others, according to a new model for how intelligent life developed on Earth.

The model, which upends the decades-old “hard steps” theory that intelligent life was an incredibly improbable event, suggests that maybe it wasn't all that hard or improbable. A team of researchers at Penn State, who led the work, said the new interpretation of humanity’s origin increases the probability of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe.

“This is a significant shift in how we think about the history of life,” said Jennifer Macalady, professor of geosciences at Penn State and co-author on the paper, which published today (Feb. 14) in the journal Science Advances. “It suggests that the evolution of complex life may be less about luck and more about the interplay between life and its environment, opening up exciting new avenues of research in our quest to understand our origins and our place in the universe.”

Initially developed by theoretical physicist Brandon Carter in 1983, the “hard steps” model argues that our evolutionary origin was highly unlikely due to the time it took for humans to evolve on Earth relative to the total lifespan of the sun — and therefore the likelihood of human-like beings beyond Earth is extremely low.

In the new study, a team of researchers that included astrophysicists and geobiologists argued that Earth's environment was initially inhospitable to many forms of life, and that key evolutionary steps only became possible when the global environment reached a "permissive" state.

For example, complex animal life requires a certain level of oxygen in the atmosphere, so the oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere through photosynthesizing microbes and bacteria was a natural evolutionary step for the planet, which created a window of opportunity for more recent life forms to develop, explained Dan Mills, postdoctoral researcher at The University of Munich and lead author on the paper.

“We're arguing that intelligent life may not require a series of lucky breaks to exist,” said Mills, who worked in Macalady’s astrobiology lab at Penn State as an undergraduate researcher. “Humans didn't evolve ‘early’ or ‘late’ in Earth’s history, but ‘on time,’ when the conditions were in place. Perhaps it’s only a matter of time, and maybe other planets are able to achieve these conditions more rapidly than Earth did, while other planets might take even longer.”

The central prediction of the “hard steps” theory states that very few, if any, other civilizations exist throughout the universe, because steps such as the origin of life, the development of complex cells and the emergence of human intelligence are improbable based on Carter’s interpretation of the sun's total lifespan being 10 billion years, and the Earth's age of around 5 billion years.

In the new study, the researchers proposed that the timing of human origins can be explained by the sequential opening of “windows of habitability” over Earth's history, driven by changes in nutrient availability, sea surface temperature, ocean salinity levels and the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere. Given all the interplaying factors, they said, the Earth has only recently become hospitable to humanity — it’s simply the natural result of those conditions at work.

“We’re taking the view that rather than base our predictions on the lifespan of the sun, we should use a geological time scale, because that's how long it takes for the atmosphere and landscape to change,” said Jason Wright, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State and co-author on the paper. “These are normal timescales on the Earth. If life evolves with the planet, then it will evolve on a planetary time scale at a planetary pace.”

Wright explained that part of the reason that the “hard steps” model has prevailed for so long is that it originated from his own discipline of astrophysics, which is the default field used to understand the formation of planets and celestial systems. The team’s paper is a collaboration between physicists and geobiologists, each learning from each other’s fields to develop a nuanced picture of how life evolves on a planet like Earth.

“This paper is the most generous act of interdisciplinary work,” said Macalady, who also directs Penn State’s Astrobiology Research Center. “Our fields were far apart, and we put them on the same page to get at this question of how we got here and are we alone? There was a gulf, and we built a bridge.”

The researchers said they plan to test their alternative model, including questioning the unique status of the proposed evolutionary “hard steps.” The recommended research projects are outlined in the current paper and include such work as searching the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system for biosignatures, like the presence of oxygen. The team also proposed testing the requirements for proposed “hard steps” to determine how hard they actually are by studying uni- and multicellular forms of life under specific environmental conditions such as lower oxygen and temperature levels.

Beyond the proposed projects, the team suggested the research community should investigate whether innovations —such as the origin of life, oxygenic photosynthesis, eukaryotic cells, animal multicellularity and Homo sapiens — are truly singular events in Earth's history. Could similar innovations have evolved independently in the past, but evidence that they happened was lost due to extinction or other factors?

“This new perspective suggests that the emergence of intelligent life might not be such a long shot after all,” Wright said. “Instead of a series of improbable events, evolution may be more of a predictable process, unfolding as global conditions allow. Our framework applies not only to Earth, but also other planets, increasing the possibility that life similar to ours could exist elsewhere.”

The other co-author on the paper is Adam Frank of the University of Rochester. Penn State’s Astrobiology Research Center, the Penn State Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, the Penn State Extraterrestrial Intelligence Center, the NASA Exobiology program and the German Research Foundation supported this work.

END

Does planetary evolution favor human-like life? Study ups odds we’re not alone

New theory proposes that humans — and analogous life beyond Earth — may represent the probable outcome of biological and planetary evolution

2025-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Clearing the way for faster and more cost-effective separations

2025-02-14

CLEVELAND—The process of separating useful molecules from mixtures of other substances accounts for 15% of the nation’s energy, emits 100 million tons of carbon dioxide and costs $4 billion annually.

Commercial manufacturers produce columns of porous materials to separate potential new drugs developed by the pharmaceutical industry, for example, and also for energy and chemical production, environmental science and making foods and beverages.

But in a new study, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have found these ...

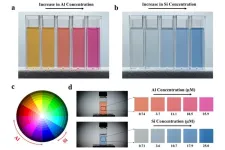

Researchers develop a five-minute quality test for sustainable cement industry materials

2025-02-14

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new test developed at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign can predict the performance of a new type of cementitious construction material in five minutes — a significant improvement over the current industry standard method, which takes seven or more days to complete. This development is poised to advance the use of next-generation resources called supplementary cementitious materials — or SCMs — by speeding up the quality-check process before leaving the production floor.

Due ...

Three Texas A&M professors elected to National Academy Of Engineering

2025-02-14

Drs. Vanderlei Bagnato, Rodney Bowersox and Don Lipkin from Texas A&M University’s College of Engineering have been elected to the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) Class of 2025, joining 128 new members and 22 international members. This is one of the highest professional honors for engineers.

“Congratulations to Drs. Bagnato, Bowersox and Lipkin for achieving this recognition. This prestigious honor reflects their groundbreaking contributions to engineering and underscores the exceptional talent within our faculty,” said Dr. Robert H. Bishop, vice chancellor and dean of Texas A&M ...

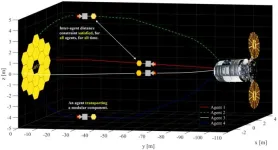

New research sheds light on using multiple CubeSats for in-space servicing and repair missions

2025-02-14

As more satellites, telescopes, and other spacecraft are built to be repairable, it will take reliable trajectories for service spacecraft to reach them safely. Researchers in the Department of Aerospace Engineering in The Grainger College of Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign are developing a methodology that will allow multiple CubeSats to act as servicing agents to assemble or repair a space telescope. Their method minimizes fuel consumption, guarantees that servicing agents never come closer to each other ...

Research suggests comprehensive CT scans may help identify atherosclerosis among lung cancer patients

2025-02-14

Several cardiovascular risk factors, such as advanced age and smoking history, are prevalent among lung cancer patients at the time of the diagnosis and increase their risk of future heart disease, according to a new study being presented at ACC’s Advancing the Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient course. Comprehensive assessments are needed in this vulnerable group to improve survival outcomes and quality of care for cancer patients.

Heart disease and cancer are the leading causes of death in the United States. Smoking is a shared risk factor for lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer patients have an amplified mortality rate with the presence of ...

Adults don’t trust health care to use AI responsibly and without harm

2025-02-14

A study finds that 65.8% of adults surveyed had low trust in their health care system to use artificial intelligence responsibly and 57.7% had low trust in their health care systems to make sure an AI tool would not harm them.

The research letter was published in JAMA Network Open.

Adults who had higher levels of overall trust in their health care systems were more likely to believe their providers would protect them from AI-related harm.

The letter, authored by Jodyn Platt, Ph.D., of the Department of Learning Health Sciences at University of Michigan Medical School and Paige Nong, Ph.D., of the University of Minnesota School of Public Health comes from survey of a nationally ...

INSEAD webinar on the dual race to AI & global leadership

2025-02-14

Digital@INSEAD is hosting a free TECH TALK X webinar “The Dual Race to AI & Global Leadership” on Wednesday, 19 February 2025 7.00 am ET / 1.00 pm CET (Duration: 60 min).

The TECH TALK will be featuring a discussion between Tim Gordon (MBA’00D), Partner, Best Practice AI and Theos Evgeniou, INSEAD Professor of Technology & Business and Director of Executive Programs in AI.

Tim, an INSEAD alumnus with over 20 years of international experience in digital transformation, global strategy and innovation, will join Theos to explore the two critical AI races reshaping our world: ...

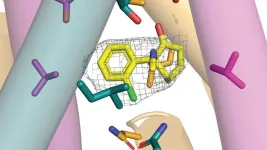

Ketamine: From club drug to antidepressant?

2025-02-14

Ketamine has received a Hollywood makeover. It used to be known as a rave drug (street name special K) and cat anesthetic. However, in recent years, some doctors have prescribed ketamine to treat conditions from post-traumatic stress disorder to depression. “The practice is not without controversy,” notes Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Hiro Furukawa.

‘Should we give a hallucinogen to patients in compromised mental states?’ wonder ketamine’s skeptics. The controversy came to ...

Multilevel stressors and systemic and tumor immunity in Black and White women with breast cancer

2025-02-14

About The Study: The findings of this cross-sectional study of Black and white women with breast cancer suggest that perceived stress, perceived inadequate social support, perceived racial and ethnic discrimination, and neighborhood deprivation were associated with deleterious alterations to the systemic and tumor immune environment, particularly for Black women. Understanding biology as a possible mediator of cancer health disparities may inform prevention and public health interventions.

Corresponding Author: To contact ...

Childhood lifestyle behaviors and mental health symptoms in adolescence

2025-02-14

About The Study: This cohort study of Finnish children and adolescents found that higher physical activity and lower screen time from childhood were associated with perceived stress and depressive symptoms in adolescence. These findings emphasize reducing screen time and increasing physical activity to promote mental health in youth.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Eero A. Haapala, PhD, email eero.a.haapala@jyu.fi.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.60012)

Editor’s Note: Please see the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] Does planetary evolution favor human-like life? Study ups odds we’re not aloneNew theory proposes that humans — and analogous life beyond Earth — may represent the probable outcome of biological and planetary evolution