(Press-News.org) A Chinese rover that landed on Mars in 2021 detected evidence of underground beach deposits in an area thought to have once been the site of an ancient sea, providing further evidence that the planet long ago had a large ocean.

The now-inactive rover, called Zhurong, operated for a year, between May 2021 and May 2022. It traveled 1.9 kilometers (1.2 miles) roughly perpendicular to escarpments thought to be an ancient shoreline from a time — 4 billion years ago — when Mars had a thicker atmosphere and a warmer climate. Along its path, the rover used ground penetrating radar (GPR) to probe up to 80 meters (260 feet) beneath the surface. This radar is used to detect underground objects, such as pipes and utilities, but also irregular features, such as boundaries between rock layers or unmarked graves.

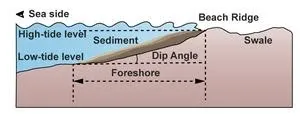

The radar images showed thick layers of material along the entire path, all pointing upward toward the putative shoreline at about a 15-degree angle, nearly identical to the angle of beach deposits on Earth. Deposits of this thickness on Earth would have taken millions of years to form, suggesting that Mars had a long-lived body of water with wave action to distribute the sediments along a sloping shoreline.

The radar was also able to determine the size of the particles in these layers, which matched that of sand. Yet, the deposits don't resemble ancient, wind-blown dunes, which are common on Mars.

"The structures don't look like sand dunes. They don't look like an impact crater. They don't look like lava flows. That's when we started thinking about oceans," said Michael Manga, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of earth and planetary science. "The orientation of these features are parallel to what the old shoreline would have been. They have both the right orientation and the right slope to support the idea that there was an ocean for a long period of time to accumulate the sand-like beach."

Manga is the contributing author of a paper about the Zhurong measurements to be published the week of Feb. 24 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

According to the paper's Chinese and American authors, beaches imply a large, ice-free ocean on Mars, even though Mars is too cold today for water to flow as a liquid. They also imply that there were rivers that dumped sediment into the ocean that was distributed by waves along the beaches.

"The presence of these deposits requires that a good swath of the planet, at least, was hydrologically active for a prolonged period in order to provide this growing shoreline with water, sediment and potentially nutrients," said co-author Benjamin Cardenas, an assistant professor of geosciences at The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State). "Shorelines are great locations to look for evidence of past life. It’s thought that the earliest life on Earth began at locations like this, near the interface of air and shallow water."

"This strengthens the case for past habitability in this region on Mars," said Hai Liu, a professor with the School of Civil Engineering and Transportation at Guangzhou University and a core member of the science team for the Tianwen-1 mission, which included China's first Mars rover, Zhurong.

Deuteronilus shoreline

Images taken by the Viking spacecraft in the 1970s first led to speculation that an ocean once existed on Mars, likely during a time when the planet had a denser atmosphere that could retain heat and thus liquid water. The Viking images showed what looked like a shoreline around a large portion of Mars’ northern hemisphere and a depression that could be an ancient seabed.

Yet, the shoreline was so irregular, with ups and downs of up to 10 km, that planetary scientists doubted this scenario. Shorelines, like those on Earth, should be level. Other conundrums, such as what happened to the water, also cast doubt on this theory. The polar ice caps do not contain enough water to fill such an ocean.

Subsequent missions to Mars, however, provided evidence that, while a lot of the planet's water likely escaped to space along with Mars' atmosphere as the planet cooled, much probably also went underground, either as ice or combined with rocks to form new minerals.

In 2007, Manga and his colleagues proposed a theory to explain how today's uneven shoreline could have been created by an ocean. Based on computer modeling, they argued that the planet's huge volcanic region, Tharsis, which contains the solar system's largest volcanoes, altered the planet's rotation after it formed about 3.7 billion years ago, making the level shoreline uneven. He revised that theory in 2017, suggesting that Mars' rotation actually changed while the Tharsis bulge formed, starting about 4 billion years ago.

"Because the spin axis of Mars has changed, the shape of Mars has changed. And so what used to be flat is no longer flat," he said.

With its ground penetrating radar, Zhurong had an opportunity to look for underground evidence of an ancient ocean.

"The southern Utopia Planitia, where Zhurong landed on May 15, 2021, is one of the largest impact basins on Mars and has long been hypothesized to have once contained an ancient ocean," Liu said. "Studying this area provides a unique opportunity to investigate whether large bodies of water ever existed in Mars’ northern lowlands and to understand the planet’s climate history."

Hai and Zhurong scientists reached out to Manga through Cardenas to help interpret the GPR data primarily because of Manga's long interest in Mars' oceans. Manga says that the Rover Penetrating Radar (RoPeR) detected radar reflections about 10 meters below the current surface that are classic indications of sloping, sandy beaches lining an ocean.

"The sand that's on those beaches is coming in from the rivers, and then it's being transported by currents in the ocean and continually being transported up and down the beaches by the waves coming and going up and down the beach," Manga said, noting that Mars has many features that look like ancient rivers. "So there must have been rivers transporting sediment to the ocean, though there's nothing in the immediate vicinity that would have disturbed these beach deposits."

In January 2025, other researchers reported evidence of ripples in sedimentary rocks at the bottom of Gale Crater, the landing site for NASA's Curiosity rover, suggesting the presence of long-gone bodies of liquid water with no ice covering the surface. The Perseverance rover has also found evidence of a river delta in Jezero crater, a mere 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) from Zhurong's landing site. But both of these craters are thought to have been lakes, not oceans.

"To make ripples by waves, you need to have an ice-free lake. Now we're saying we have an ice-free ocean. And rather than ripples, we're seeing beaches," Manga said.

The approximately 10 meters (30 feet) of material overlaying the beach deposits were likely deposited by dust storms, material thrown out by asteroid impacts or volcanic eruptions over the billions of years since the ocean disappeared. This turned out to be fortuitous, Cardenas said.

"The shoreline deposits imaged here are pristine, still in the subsurface," he said. "There has been a lot of shoreline work done, but it’s always a challenge to know how the last 3.5 billion years of erosion on Mars might have altered or completely erased evidence of an ocean. But not with these deposits. This is a very unique dataset."

Other co-authors of the paper are Liu's colleagues at Guangzhou University, Jianhui Li, Xu Meng, Diwen Duan and Haijing Lu; Jinhai Zhang, Bin Zhou and Guangyou Fang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing; Fengshou Zhang of Tongji University in Shanghai; and Derek Elsworth of Penn State. Fang, who is with the Aerospace Information Research Institute, developed the Rover Penetrating Radar for Tianwen-1.

The Chinese team was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation. Manga was supported by the Earth4D program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

END

Ancient beaches testify to long-ago ocean on Mars

Chinese rover finds underground evidence of beach sediments likely deposited 4 billion years ago

2025-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gulf of Mars: Rover finds evidence of ‘vacation-style’ beaches on Mars

2025-02-24

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Mars may have once been home to sun-soaked, sandy beaches with gentle, lapping waves according to a new study published today (Feb. 24) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

An international team of scientists, including Penn State researchers, used data from the Zhurong Mars rover to identify hidden layers of rock under the planet’s surface that strongly suggest the presence of an ancient northern ocean. The new research offers the clearest evidence yet that the planet ...

MSU researchers use open-access data to study climate change effects in 24,000 US lakes

2025-02-24

Feb. 24, 2025

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Contact: Emilie Lorditch: 517-355-4082, lorditch@msu.edu

Images

MSU researchers use open-access data to study climate change effects in 24,000 US lakes

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Each summer, more and more lake beaches are forced to close due to toxic algae blooms. While climate change is often blamed, new research suggests a more complex story: climate interacts with human activities like agriculture and urban runoff, which funnel excess ...

More than meets the eye: An adrenal gland tumor is more complex than previously thought

2025-02-24

Fukuoka, Japan - Kyushu University researchers have uncovered a surprising layer of complexity in aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs)—adrenal gland tumors that drive high blood pressure. Using cutting-edge analysis techniques, they discovered that these tumors harbor at least four distinct cell types, including ones that produce cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone. Published in the week beginning 24 February in PNAS, their findings not only explain why some patients with APAs develop unexpected health issues, like weakened bones, but also pave the way toward new treatment strategies.

“Currently, the only ...

Origin and diversity of Hun Empire populations

2025-02-24

The Huns suddenly appeared in Europe in the 370s, establishing one of the most influential although short-lived empires in Europe. Scholars have long debated whether the Huns were descended from the Xiongnu. In fact, the Xiongnu Empire dissolved around 100 CE, leaving a 300-year gap before the Huns appeared in Europe. Can DNA lineages that bridge these three centuries be found?

To address this question, researchers analyzed the DNA of 370 individuals that lived in historical periods spanning around 800 years, from 2nd century BCE to 6th century CE, encompassing sites in the Mongolian steppe, Central Asia, and the Carpathian Basin of Central Europe. ...

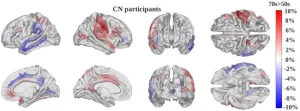

New AI model measures how fast the brain ages

2025-02-24

A new artificial intelligence model measures how fast a patient’s brain is aging and could be a powerful new tool for understanding, preventing and treating cognitive decline and dementia, according to USC researchers.

The first-of-its-kind tool can non-invasively track the pace of brain changes by analyzing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Faster brain aging closely correlates with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, said Andrei Irimia, associate professor of gerontology, biomedical engineering, quantitative ...

This new treatment can adjust to Parkinson's symptoms in real time

2025-02-24

Starting today, people with Parkinson’s disease will have a new treatment option, thanks to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of groundbreaking new technology.

The therapy, known as adaptive deep brain stimulation, or aDBS, uses an implanted device that continuously monitors the brain for signs that Parkinson’s symptoms are developing. When it detects specific patterns of brain activity, it delivers precisely calibrated electric pulses to keep symptoms at bay.

The FDA approval covers two treatment algorithms that run on a device made by Medtronic, a medical device company. Both work by monitoring the same part of the brain, called the subthalamic nucleus. ...

Bigger animals get more cancer, defying decades-old belief

2025-02-24

Elephants, giraffes, pythons and other large species have higher cancer rates than smaller ones like mice, bats, and frogs, a new study has shown, overturning a 45-year-old belief about cancer in the animal kingdom.

The research, conducted by researchers from the University of Reading, University College London and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, examined cancer data from 263 species across four major animal groups - amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles. The findings challenge "Peto's paradox," a longstanding idea based on observations from 1977 that suggested ...

As dengue spreads, researchers discover a clue to fighting the virus

2025-02-24

LA JOLLA, CA—Children who experience multiple cases of dengue virus develop an army of dengue-fighting T cells, according to a new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI).

The findings, published recently in JCI Insights, suggest that these T cells are key to dengue virus immunity. In fact, most children who experienced two or more dengue infections showed very minor symptoms—or no symptoms at all—when they caught the virus again.

"We saw a significant T cell response in children who had been infected more than once before," says study leader and LJI Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D.

Dengue virus infects up ...

Teaming up tiny robot swimmers to transform medicine

2025-02-24

Smart artificial microswimmers—small robots that resemble microorganisms like bacteria or human sperm—could potentially be used for targeted drug delivery, minimally invasive surgery, and even in fertility treatments.

These types of complicated tasks won’t be accomplished by a single microswimmer. Multiple swimmers will be necessary; however, it’s unclear how such groups will move within the chemically and mechanically complex environment of the body’s fluids.

“We know that whenever a swimmer has a neighbor, it swims differently,” says Ebru Demir, an assistant ...

The Center for Open Science welcomes Daniel Correa and Amanda Kay Montoya to its Board of Directors

2025-02-24

(Charlottesville, VA, Feb. 24, 2025) –

The Center for Open Science (COS) is pleased to announce the appointment of Daniel Correa, Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, and Amanda Montoya, Associate Professor of Quantitative Psychology at UCLA, to the COS Board of Directors. Both will serve three-year terms from 2025 to 2027, bringing valuable expertise in science policy, innovation, research methodology, and open science advocacy.

Daniel Correa is the Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists ID potential treatment for deadliest brain cancer

If you want to feel gratitude in your life, embrace nostalgia, VCU research finds

Malaria: Newly identified “crown” stage controls parasite reproduction

SwRI appoints Fuselier vice president of Space Science Division

What's the ROI on R&D in aging? New simulation tool, silverlingings.bio, explores geroscience's impact on US GDP growth and individual health

CFC replacements behind hundreds of thousands of tonnes of global ‘forever chemical’ pollution

Pigs and grizzlies, not monkeys, hold clues to youthful human skin

Innovative card deck by Case Western Reserve professor empowers kids to tackle stress head-on

From STEM to social impact: U-M scholars go global with Fulbright awards

Calling for young editorial board members

Blocking pain at the source: Hormone therapy rewires nerve signals in aging spines

Green chemistry: Friendly bacteria can unlock hidden metabolic pathways in plant cell cultures

NCCN commemorates World Cancer Day with new commitment to update patient resources

Uncommon names are increasing globally: Reflecting an increase in uniqueness-seeking and individualism

Windows into the past: Genetic analysis of Deep Maniot Greeks reveals a unique genetic time capsule in the Balkans

Researchers quantify role of reducing obesity in preventing common conditions

Sugar molecules point to a new weapon against drug-resistant bacteria

WHO calls for mental health to be central to neglected tropical disease care

Stacking the genetic deck: How some plant hybrids beat the odds

KRICT demonstrates 100kg per day sustainable aviation fuel production from landfill gas

High consumption of ultraprocessed foods may be linked to cancer survivors’ risk of death

Unsupervised strategies for naïve animals: New model of adaptive decision making inspired by baby chicks, turtles and insects

How cities primed spotted lanternflies to thrive in the US

UK polling clerks struggle to spot fake IDs, study reveals

How mindfulness can support GenAI use in transforming project management

Physical fitness of transgender and cisgender women is comparable, current evidence suggests

Duplicate medical records linked to 5-fold heightened risk of inpatient death

Air ambulance pre-hospital care may make surviving critical injury more likely

Significant gaps persist in regional UK access to 24/7 air ambulance services

Reproduction in space, an environment hostile to human biology

[Press-News.org] Ancient beaches testify to long-ago ocean on MarsChinese rover finds underground evidence of beach sediments likely deposited 4 billion years ago