(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Mars has captivated scientists and the public alike for centuries. One of the biggest reasons is the planet’s reddish hue, earning the third rock from the sun one its most popular nicknames — the “Red Planet.” But what exactly gives the planet its iconic color? Scientists have wondered this for as long as they’ve studied the planet. Today, they may finally have a concrete answer, one that ties into Mar’s watery past.

Results from a new study published in the journal Nature Communications and led by researchers from Brown University and the University of Bern suggest that the water-rich iron mineral ferrihydrite may be the main culprit behind Mars’ reddish dust. Their theory — which they reached by analyzing data from Martian orbiters, rovers and laboratory simulations — runs counter to the prevailing theory that a dry, rust-like mineral called hematite is the reason for the planet’s color.

“The fundamental question of why Mars is red has been thought of for hundreds if not for 1000s of years,” said Adomas (Adam) Valantinas, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown who started this work as a Ph.D. student at the University of Bern. “From our analysis, we believe ferrihydrite is everywhere in the dust and also probably in the rock formations, as well. We’re not the first to consider ferrihydrite as the reason for why Mars is red, but it has never been proven the way we proved it now using observational data and novel laboratory methods to essentially make a Martian dust in the lab.”

Ferrihydrite is an iron oxide mineral that forms in water-rich environments. On Earth, it is commonly associated with processes like the weathering of volcanic rocks and ash. Until now, its role in Mars' surface composition was not well understood, but this new research suggests that it could be an important part of the dust that blankets the planet’s surface.

The finding offers a tantalizing clue to Mars’ wetter and potentially more habitable past because unlike hematite, which typically forms under warmer, drier conditions, ferrihydrite forms in the presence of cool water. This suggests that Mars may have had an environment capable of sustaining liquid water — an essential ingredient for life — and that it transitioned from a wet to a dry environment billions of years ago.

“What we want to understand is the ancient Martian climate, the chemical processes on Mars — not only ancient — but also present,” said Valantinas, who is working in the lab of Brown planetary scientist Jack Mustard, a senior author on the study. “Then there’s the habitability question: Was there ever life? To understand that, you need to understand the conditions that were present during the time of this mineral formation. What we know from this study is the evidence points to ferrihydrite forming, and for that to happen there must have been conditions where oxygen, from air or other sources, and water could react with iron. Those conditions were very different from today's dry, cold environment. As Martian winds spread this dust everywhere, it created the planet's iconic red appearance.”

The researchers analyzed data from multiple Mars missions, combining orbital observations from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the European Space Agency's Mars Express and Trace Gas Orbiter with ground-level measurements from rovers like Curiosity, Pathfinder and Opportunity.

Instruments on the orbiters and rovers provided detailed spectral data of the planet’s dusty surface. These findings were then compared to laboratory experiments, where the team tested how light interacts with ferrihydrite particles and other minerals under simulated Martian conditions.

“Martian dust is very small in size, so to conduct realistic and accurate measurements we simulated the particle sizes of our mixtures to fit the ones on Mars,” Valantinas said. “We used an advanced grinder machine which reduced the size of our ferrihydrite and basalt to submicron sizes. The final size was 1/100th of a human hair and the reflected light spectra of these mixtures provide a good match to the observations from orbit and red surface on Mars.”

As exciting as these new findings are, the researchers are well aware none of it can be confirmed until samples from Mars are brought back to Earth, leaving the mystery of the Red Planet’s past just out of reach.

“The study is a door opening opportunity,” Mustard said. “It gives us a better chance to apply principles of mineral formation and conditions to tap back in time. What’s even more important though is the return of the samples from Mars that are being collected right now by the Perseverance rover. When we get those back, we can actually check and see if this is right.”

END

Why is Mars red? Scientists may finally have the answer

A new study led by Brown University researchers shows a water-rich mineral could explain the planet’s color — and hint at its wetter, more habitable past.

2025-02-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research challenges our understanding of cancer predisposition

2025-02-25

Despite what was previously thought, new research has shown that genetic changes alone cannot explain why and where tumours grow in those with genetic condition neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). Understanding more about the factors involved could, in the future, facilitate early cancer detection in NF-1 patients and even point towards new treatments.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and their collaborators, focused on NF-1, a genetic condition that causes ...

What makes cancer cells weak

2025-02-25

One particular challenge in the treatment of cancer is therapy resistance. An international research team has now discovered a mechanism that opens up new treatment strategies for tumours in which conventional chemotherapeutic agents have reached their limits. "Cytotoxic agents from nature lead to an increased incorporation of polyunsaturated fatty acids into the membrane of cancer cells. This makes them more susceptible to ferroptosis, a type of cell death, at a very early stage," reports Andreas Koeberle, a pharmacist at the University of Graz and lead author of the study, which has just been published in the scientific journal Nature ...

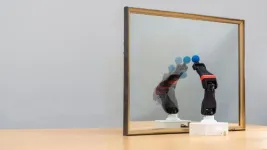

Robots learn how to move by watching themselves

2025-02-25

New York, NY—Feb. 25, 2025— By watching their own motions with a camera, robots can teach themselves about the structure of their own bodies and how they move, a new study from researchers at Columbia Engineering now reveals. Equipped with this knowledge, the robots could not only plan their own actions, but also overcome damage to their bodies.

"Like humans learning to dance by watching their mirror reflection, robots now use raw video to build kinematic self-awareness," says study lead author Yuhang Hu, a doctoral student at the Creative Machines Lab at Columbia University, directed by Hod Lipson, James and Sally Scapa Professor of Innovation and chair of the Department ...

MD Anderson researchers develop novel antibody-toxin conjugate

2025-02-25

HOUSTON ― Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have developed a novel antibody-toxin conjugate (ATC) designed to stimulate immune-mediated eradication of tumors. According to preclinical results published today in Nature Cancer, the new approach combined the benefits of more well-known antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) with those of immunotherapies.

ADCs have emerged as a breakthrough in recent years due to their modular design, which enables precise delivery of therapies to tumors by targeting specific proteins expressed on cancer cells. These conjugates ...

One in ten older South Asian immigrants in Canada have hypothyroidism

2025-02-25

Toronto, ON – A new study published this week in Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics Plus found that 10% of South Asian immigrants aged 45 and older in Canada had hypothyroidism. After adjustment for a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics and health behaviors, those who had immigrated from South Asia had 77% higher odds of hypothyroidism than those born in Canada.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a significantly higher odds of hypothyroidism among immigrants of South Asian descent,” says senior author Esme Fuller-Thomson, a Professor at Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW) and Director ...

Substantial portion of cancer patients in early trials access drugs that are later approved

2025-02-25

A new paper in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, published by Oxford University Press, finds that almost 20% of patients in middle-stage cancer drug trials receive treatment that eventually prove effective enough to get FDA approval. This may have important implications for drug development and clinical trial recruitment.

The development of new medications typically has three stages. In phase 1 trials, researchers assess drugs for safety and dosing (“What is the best tolerated dose for the patient?”). Phase 2 clinical trials determine whether a new drug shows signs of efficacy (“How much does the ...

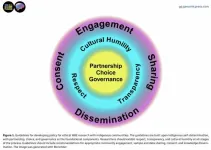

New study calls for ethical framework to protect Indigenous genetic privacy in wastewater monitoring

2025-02-25

GUELPH, Ontario, Canada, 25 February 2025 – In a comprehensive peer-reviewed Perspective (review) article, researchers from the University of Guelph have outlined an urgent call for new ethical frameworks to protect Indigenous communities' genetic privacy in the growing field of wastewater surveillance. The study, published today in Genomic Psychiatry (Genomic Press New York), examines how the analysis of community wastewater – while valuable for public health monitoring – raises significant privacy concerns for Indigenous populations.

"Wastewater-based ...

Common medications may affect brain development through unexpected cholesterol disruption

2025-02-25

OMAHA, Nebraska, USA, 25 February 2025 - In a peer-reviewed Perspective (review) article, researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center have uncovered concerning evidence that commonly prescribed medications may interfere with crucial brain development processes by disrupting sterol biosynthesis. Their findings, published today in Brain Medicine (Genomic Press, New York), suggest that this previously overlooked mechanism could have significant implications for medication safety during pregnancy and early development.

"What we've discovered is that many prescription medications, while designed for entirely different purposes, can inadvertently interfere with the brain's ...

Laser-powered device tested on Earth could help us detect microbial fossils on Mars

2025-02-25

The first life on Earth formed four billion years ago, as microbes living in pools and seas: what if the same thing happened on Mars? If it did, how would we prove it? Scientists hoping to identify fossil evidence of ancient Martian microbial life have now found a way to test their hypothesis, proving they can detect the fossils of microbes in gypsum samples that are a close analogy to sulfate rocks on Mars.

“Our findings provide a methodological framework for detecting biosignatures in Martian sulfate minerals, potentially guiding ...

Non-destructive image sensor goes beyond bulkiness

2025-02-25

While photo-thermoelectric (PTE) sensors are potentially suitable for testing applications, such as non-destructive material-identification in ultrabroad millimeter-wave (MMW)–infrared (IR) bands, their device designs have primarily employed a single material as the channel. In general, PTE sensors combine photo-induced heating with associated thermoelectric (TE) conversion, and the employment of a single material channel regulates the utilization of devices by missing the opportunity for fully utilizing their fundamental parameters. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Here's why seafarers have little confidence in autonomous ships

MYC amplification in metastatic prostate cancer associated with reduced tumor immunogenicity

The gut can drive age-associated memory loss

Enhancing gut-brain communication reversed cognitive decline, improved memory formation in aging mice

Mothers exposure to microbes protect their newborn babies against infection

How one flu virus can hamper the immune response to another

Researchers uncover distinct tumor “neighborhoods”, with each cell subtype playing a specific role, in aggressive childhood brain cancer

Researchers develop new way to safely insert gene-sized DNA into the genome

Astronomers capture birth of a magnetar, confirming link to some of universe’s brightest exploding stars

New photonic device, developed by MIT researchers, efficiently beams light into free space

UCSB researcher bridges the worlds of general relativity and supernova astrophysics

Global exchange of knowledge and technology to significantly advance reef restoration efforts

Vision sensing for intelligent driving: technical challenges and innovative solutions

To attempt world record, researchers will use their finding that prep phase is most vital to accurate three-point shooting

AI is homogenizing human expression and thought, computer scientists and psychologists say

Severe COVID-19, flu facilitate lung cancer months or years later, new research shows

Housing displacement, employment disruption, and mental health after the 2023 Maui wildfires

GLP-1 receptor agonist use and survival among patients with type 2 diabetes and brain metastases

Solid but fluid: New materials reconfigure their entire crystal structure in response to humidity

New research reveals how development and sex shape the brain

New discovery may improve kidney disease diagnosis in black patients

What changes happen in the aging brain?

Pew awards fellowships to seven scientists advancing marine conservation

Turning cancer’s protein machinery against itself to boost immunity

Current Pharmaceutical Analysis releases Volume 22, Issue 2 with open access research

Researchers capture thermal fluctuations in polymer segments for the first time

16-year study finds major health burden in single‑ventricle heart

Disposable vapes ban could lead young adults to switch to cigarettes, study finds

Adults with concurrent hearing and vision loss report barriers and challenges in navigating complex, everyday environments

Breast cancer stage at diagnosis differs sharply across rural US regions

[Press-News.org] Why is Mars red? Scientists may finally have the answerA new study led by Brown University researchers shows a water-rich mineral could explain the planet’s color — and hint at its wetter, more habitable past.