(Press-News.org)

Gas sensing technologies play a vital role in our modern world, from ensuring our safety in homes and workplaces to monitoring environmental pollution and industrial processes. Traditional gas sensors, while effective, often face limitations in their sensitivity, response time, and power consumption.

To account for these drawbacks, recent developments in gas sensors have focused on carbon nanomaterials, including the ever-popular graphene. This versatile and relatively inexpensive material can provide exceptional sensitivity at room temperature while consuming minimal power. Thus, graphene holds the potential to revolutionize gas detection systems.

Against this backdrop, a research team led by Associate Professor Tomonori Ohba from the Graduate School of Science, Chiba University, Japan, explored a promising avenue to improve graphene’s sensing properties even further. As reported in their latest paper, which was published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, the team investigated how and why graphene sheets treated by plasma with different gases can lead to enhanced sensitivity for ammonia (NH3), a toxic compound. The study was made available online on December 26, 2024, and was published on January 8, 2025, in Volume 17, Issue 1. This study was co-authored by Mr. Sogo Iwakami and Mr. Shunya Yakushiji, also from Chiba University.

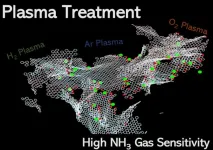

The researchers produced graphene sheets and applied a plasma treatment to them under argon (Ar), hydrogen (H2), or oxygen (O2) environments. This treatment “functionalized” graphene, meaning that it modified the surface of the graphene sheets by attaching specific chemical groups and creating controlled defects, serving as additional binding sites for gas molecules like NH3. After treatment, the researchers employed a variety of advanced spectroscopic techniques and theoretical calculations to shed light on the precise chemical and structural changes the graphene sheets underwent.

The team found that the gas used during plasma treatment led to the creation of different types of defects on the graphene sheets. “The O2 plasma treatment induced oxidation of the graphene, producing graphoxide, whereas the H2 plasma treatment induced hydrogenation, producing graphane,” explains Assoc. Prof. Ohba, “Spectroscopic analysis suggested that graphoxide had carbon vacancy-type defects, graphane had sp3-type defects, and Ar-treated graphene had both types of defects.” To clarify, an sp3-type defect is a structural change where a carbon atom in graphene shifts from having three bonds in a flat plane to forming four bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, often due to hydrogen atoms attaching to the surface.

Interestingly, introducing these defects into the graphene sheets greatly enhanced their performance for sensing NH3. Since NH3 binds more easily to defects rather than to pristine graphene, the electrical conductivity of functionalized sheets changed more noticeably when exposed to NH3. This property can be leveraged in gas-sensing devices to detect and quantify the presence of NH3. Graphoxide, in particular, exhibited the greatest changes in sheet resistance (the inverse of conductivity) when exposed to NH3—these changes were as high as 30%.

Worth noting, the team tested whether functionalized graphene sheets could withstand repeated exposure to NH3 without degrading their gas-sensing performance. Although some irreversible changes in sheet resistance were observed, some significant changes were fully reversible and cyclable. “The results showed that functionalizing graphene structures with plasma generated noble materials with a superior NH3 gas-sensing performance compared with pristine graphene,” concludes Assoc. Prof. Ohba.

Overall, this study serves as an important stepping stone toward next-generation gas-sensing devices. Excited about their findings, Assoc. Prof. Ohba remarks: “As graphene is among the thinnest possible sheets with gas permeability, the functionalized graphene sheets developed in this work could be used in daily wearable devices. Thus, in the future, anyone would be able to detect harmful gases in their surroundings.” Hopefully, further work in this field will make this vision a reality and push graphene-based technology forward.

About Associate Professor Tomonori Ohba

Tomonori Ohba is an Associate Professor and Director of the Ohba Research Group at the Department of Chemistry of the Graduate School of Science at Chiba University, Japan. He primarily works in the field of physical chemistry, aiming to elucidate chemical phenomena at the nanomolecular level by employing advanced theoretical and experimental methods. He also explores nanospaces to control molecular motion, investigate molecular behavior, and discover new molecular reactivities. His extensive research work, published in numerous reputed journals, has been cited more than 5,000 times.

END

New research highlighted in the journal CABI Reviews suggests that all five subregions of Africa will breach the 1.5°C climate change threshold – the limit stipulated by the Paris Agreement – by 2040 even under low emission scenarios.

A team of scientists, from the University of Zimbabwe, and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Kenya, conducted a literature review to develop a framework for just transition pathways for Africa’s agriculture towards low emission and climate resilient development under 1.5°C of global warming.

They found that despite Africa ...

Investigators from Mass General Brigham have conducted a multi-ancestry, whole genome sequencing association study of Alzheimer’s disease and found evidence for 16 new susceptibility genes, expanding the study of Alzheimer’s disease in underrepresented groups. Their results are published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.

For the study, co-led by Julian Daniel Sunday Willett, MD, PhD, and Mohammad Waqas, of the Genetics and Aging Research ...

A new definition of dyslexia is needed to more accurately describe the learning disorder and give those struggling with dyslexia the specific support they require, says new research.

Dyslexia has had several different definitions over the years and this murky and complicated history means it can be a postcode lottery for children who may have dyslexia, or those who have been diagnosed but can’t access the support they need.

The first step to fixing this issue, new research has argued, is to redefine dyslexia and adopt the new definition across the UK.

The research was conducted by the University of Birmingham, the SpLD Assessment Standards Committee (SASC), Kings College London, ...

More than half of women ages 30 to 35 are already suffering moderate to severe symptoms associated with menopause, yet most women are waiting decades before seeking treatment, new research from UVA Health and the Flo women’s health app reveals.

The research sheds important light on “perimenopause,” the transition period leading to menopause. Many women in perimenopause assume they’re too young to be suffering symptoms related to menopause, believing that symptoms won’t appear until they reach their 50s. But this ...

Rebels of health care use technology to connect with clinicians, information, and each other

Cambridge, MA – February 25, 2025 – The future of health care is being forged in the crucible of rare disease. A new survey led by Susannah Fox, author of Rebel Health: A Field Guide to the Patient-Led Revolution in Medical Care (The MIT Press), finds that 15% of U.S. households are affected by rare disease or an undiagnosed illness. Their lives are characterized by extreme stress, often matched by their resourcefulness.

“People living with rare diseases push the edges of what is possible by using technology ...

The Beatles said it best: Love is all you need. And according to new research from The Australian National University (ANU), the same is true in the animal kingdom. Well, at least for mosquitofish – a matchstick-sized fish endemic to Central America and now found globally.

According to the ANU scientists, male mosquitofish possess impressive problem-solving skills and can successfully navigate mazes and other tests. Males that perform better have a higher chance of mating.

Lead author Dr Ivan Vinogradov said male mosquitofish ...

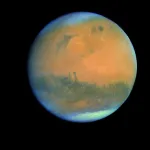

Mars is easily identifiable in the night sky by its prominent red hue. Thanks to the fleet of spacecraft that have studied the planet over the last decades, we know that this red colour is due to rusted iron minerals in the dust. That is, iron bound up in Mars’s rocks has at some point reacted with liquid water, or water and oxygen in the air, similar to how rust forms on Earth.

Over billions of years this rusty material – iron oxide – has been broken down into dust and spread all around the planet by winds, a process that continues today.

But iron ...

Statement Highlights:

It is essential for health care professionals to routinely screen pregnant and postpartum women for depression and anxiety, address modifiable risk factors and consider behavioral and pharmacological interventions to improve long-term maternal health outcomes.

Multidisciplinary care teams, including psychologists and other behavioral health professionals, are important to monitor and provide appropriate mental health support during pregnancy and after birth.

The new ...

New research from Emory University indicates that childhood trauma physically alters the hearts of Black women.

The study, which examined the relationship between childhood exposure to trauma and vascular dysfunction among more than 400 Black adults in Atlanta ages 30 to 70, found that women who experienced childhood trauma had a worse vascular function, a preclinical marker of heart disease, while men had none. In addition, the findings show women may be more vulnerable to a larger cumulative stress burden, eliciting varying physiological ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Mars has captivated scientists and the public alike for centuries. One of the biggest reasons is the planet’s reddish hue, earning the third rock from the sun one its most popular nicknames — the “Red Planet.” But what exactly gives the planet its iconic color? Scientists have wondered this for as long as they’ve studied the planet. Today, they may finally have a concrete answer, one that ties into Mar’s watery past.

Results from a new study published in the journal Nature Communications and led by researchers from Brown University and the University of Bern suggest that the water-rich iron mineral ...