(Press-News.org) A world of microbes resides within the gut of every human being. This vast microbial community, the microbiome, which includes bacteria and viruses, has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to actively contribute to both health and disease.

Researchers have learned a good deal about the bacterial communities that live in the human gut. For instance, they have discovered that these bacteria extensively metabolize the food we eat, drive normal development of the immune system and, to our detriment, include some opportunistic microorganisms that can cause disease under certain conditions.

On the other hand, the contributions of viruses in the gut microbiome to human health and disease are not known to the same extent as those of bacteria. A new study published in Nature Microbiology has changed this.

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have taken the lead on a project to investigate whether certain viruses known as bacteriophages, or phages, which specifically infect bacteria but not human cells, affect the development of type 1 diabetes in young children. Because phages exert pressure on the bacteria they infect and some phage genomes encode virulence factors and toxins, a role for specific phages or communities of phages in human health seems plausible.

“We think that phages can affect bacterial survival or behavior and this in turn could influence human health,” said first author Dr. Michael J. Tisza, assistant professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor.

The current study re-analyzed samples collected as part of The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study with the aim to specifically profile the combined phage-bacteria community. The TEDDY cohort was built with children at risk for developing immunity to the cells that produce insulin and/or type 1 diabetes. Previous TEDDY studies investigated whether gut bacteria and human viruses affected the development of type 1 diabetes. While they did not find a clear association with gut bacteria, there was an association with human viruses.

Phages are challenging to study

“Phage genetic data has been available for some time. We learned that phage genomes are very diverse, have little similarities among them and are very small, and these posed significant technical challenges to their analysis,” Tisza said. “We approached the challenge by developing a new computational tool that allowed us to analyze phage signals.”

“Using our new analytical tool, we profiled the combined phage-bacteria communities in 12,262 stool samples from 887 participants of the TEDDY study during their first four years of life,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Sara J. Javornik Cregeen, assistant professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor. “With this approach we dissected the dynamic changes in the composition of the communities of phages and bacteria in the developing gut and gained new insights into their interactions.”

The researchers found that certain bacteria thrive at different stages of human development, and this was similarly observed for phages in this study. “However, the pace at which phage communities changed was quicker than that of bacteria,” Javornik Cregeen said.

“We think this points to an arms race between bacteria and their phages in which the bacteria evolve acquiring mutations that allow them to escape predation from the phages that were infecting them, and then that opens up an opportunity for a new phage to infect the bacteria,” Tisza said.

As it relates to type 1 diabetes, the team didn't find any major phages or phage communities linked to a greater or lesser risk of developing the disease in this cohort. The findings nevertheless contribute to an improved perspective on microbiome development that reflects a dynamic interplay between phages and bacteria. The microbiome starts to develop as bacterial species enter the newly born child and begin to colonize the gut. As the child grows, a succession of bacterial species follows in response to diet changes and the development of the immune system. With this bacterial succession, phage communities also change, reflecting bacterial availability.

“As we analyzed the microbiome many times during the first years of life, it became clear that the gut of each participant is exposed to many more distinct phages than distinct bacteria, suggesting that the immune system may be exposed to more viral stimulation than was previously considered,” Tisza said.

“We hope that our findings will result in a better understanding of phage-bacteria interactions that can lead to improved therapeutic approaches to disease,” Javornik Cregeen said.

“Manipulation of the microbiome continues to be a promising path to treat a variety of diseases that involve the immune response, cardiovascular health and brain function, among others,” added co-corresponding author, Dr. Joseph Petrosino, chair and professor of molecular virology and microbiology and director of the Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor. Petrosino also is Baylor’s Chief Scientific Innovation Officer and member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. “As clinicians try to limit unnecessary antibiotic use as a primary means to combat the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections, studies such as this enable phage-based strategies to shape microbial communities to improve health and fight infectious diseases.”

The researchers are interested in continuing to explore the relationships between bacteria and phages. For instance, how phages influence the response of bacteria to perturbations such as antibiotics, change in diet or introduction of new bacteria. By evaluating temporal trends in the guts of developing children, this study helps to lay the groundwork for therapeutics and diagnostics that aim to leverage the microbiome and its constituents.

Richard E. Lloyd, Kristi Hoffman and Daniel P. Smith at Baylor College of Medicine and Marian Rewers at the University of Colorado-Aurora are co-authors of this work. For a complete list of financial support sources for this study, see the publication.

###

END

Understanding the world within: Study reveals new insights into phage–bacteria interactions in the gut microbiome

2025-02-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cold treatment does not appear to protect preterm infants from disability or death caused by oxygen loss, according to NIH-funded study

2025-02-25

WHAT:

Lowering the body temperature of preterm infants (born at 33 to 35 weeks of pregnancy) with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)—a type of brain damage caused by oxygen loss—offers no benefits over standard care, according to a study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Previous studies of near-term and term infants (born after 36 weeks) with HIE found that this cooling treatment, which lowers body temperature to about 92 degrees Fahrenheit, significantly reduced the risk of death or disability by age 18 months (corrected for prematurity). However, the current findings show ...

Pennington Biomedical researchers uncover role of hormone in influencing brain reward pathway and food preferences

2025-02-25

BATON ROUGE – When faced with multiple food options and ultimately choosing one, the factors of that decision-making process may be more physiological than previously assumed. A group of scientists led by Pennington Biomedical Research Center’s Dr. Christopher Morrison recently discovered that the hormone fibroblast growth factor 21, or FGF21, plays an influential role in brain reward mechanisms like those involved in dietary choices.

The discovery was announced in the research team’s recent paper titled “FGF21 ...

Rethinking equity in electric vehicle infrastructure

2025-02-25

As electric vehicles (EVs) gain momentum in the fight against climate change, the conversation around public charging infrastructure is growing increasingly complex. Xinwu Qian , assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University, is spearheading research that reimagines how and where charging stations should be deployed — ensuring that alignment with people’s daily routine and activities, beyond mere accessibility, are at the forefront.

“Charging an electric vehicle isn’t just about plugging it in and waiting — it takes 30 minutes to an hour even with the fastest charger ...

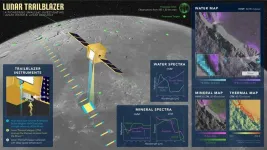

Lunar Trailblazer blasts off to map water on the moon

2025-02-25

On Wednesday 26 February, a thermal imaging camera built by researchers at the University of Oxford’s Department of Physics will blast off to the Moon as part of NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer mission. This aims to map sources of water on the Moon to shed light on the lunar water cycle and to guide future robotic and human missions.

Once in orbit, the spacecraft – weighing 200kg and about the size of a washing machine- will map the surface temperature and composition of the ...

Beacon Technology Solutions, Illinois Tech awarded grant to advance far-UVC disinfection research

2025-02-25

CHICAGO—February 24, 2025—Beacon Technology Solutions (Beacon), with collaborators at Illinois Institute of Technology (Illinois Tech), has been awarded a grant to support a novel study on how Far-UVC technology can help mitigate the spread of infectious diseases in public spaces. The grant was awarded through the Illinois Innovation Vouchers (IIV) Program, which fosters research collaborations between small- and medium-sized enterprises and Illinois’ world-class universities.

Beacon’s flagship product is a wall-mounted smart disinfection device that uses Far-UVC 222nm light, which has been shown to disinfect up to 99.99 percent ...

University of Houston researchers paving the way for new era in medical imaging

2025-02-25

New technology developed by researchers at the University of Houston could revolutionize medical imaging and lead to faster, more precise and more cost-effective alternatives to traditional diagnostic methods.

For years, doctors have relied on conventional 2D X-rays to diagnose common bone fractures, but small breaks or soft tissue damage like cancers often go undetected. More expensive and time-consuming MRI scans are not always suitable for these tasks in these detection or screening settings. Now, Mini Das, Moores professor at UH’s College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and Cullen College ...

High-tech startup CrySyst provides quality-by-control solutions for pharmaceutical, fine chemical industries

2025-02-25

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — International process systems and operation experts have launched high-tech startup Crystallization Systems Technology Inc. (CrySyst) to streamline processes used by companies in the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries.

CrySyst’s quality-by-control (QbC) framework addresses crystallization monitoring, modeling and control. The framework is based on research published in the April 15, 2020, and Oct. 5, 2021, issues of the journal Crystal Growth & Design and the Sept. 22, 2022, issue of the journal Industrial & Engineering ...

From scraps to sips: Everyday biomass produces drinking water from thin air

2025-02-25

Discarded food scraps, stray branches, seashells and many other natural materials are key ingredients in a new system that can pull drinkable water out of thin air developed by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin.

This new “molecularly functionalized biomass hydrogels” system can convert a wide range of natural products into sorbents, materials that absorb liquids. By combining these sorbents with mild heat, the researchers can harvest gallons of drinkable water out of the atmosphere, even in dry conditions.

“With ...

Scientists design novel battery that runs on atomic waste

2025-02-25

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have developed a battery that can convert nuclear energy into electricity via light emission, a new study suggests.

Nuclear power plants, which generate about 20% of all electricity produced in the United States, produce almost no greenhouse gas emissions. However, these systems do create radioactive waste, which can be dangerous to human health and the environment. Safely disposing of this waste can be challenging.

Using a combination of scintillator crystals, high-density materials that emit light when they absorb radiation, and solar cells, the team, led by researchers from The Ohio State University, demonstrated that ambient ...

“Ultra-rapid” testing unlocks cancer genetics in the operating room

2025-02-25

A novel tool for rapidly identifying the genetic “fingerprints” of cancer cells may enable future surgeons to more accurately remove brain tumors while a patient is in the operating room, new research reveals. Many cancer types can be identified by certain mutations, changes in the instructions encoded in the DNA of the abnormal cells.

Led by a research team from NYU Langone Health, the new study describes the development of Ultra-Rapid droplet digital PCR, or UR-ddPCR, which the team found can measure the level of tumor cells in a tissue sample ...