Under embargo until Wednesday 5 March 2025, 16:00 UK time / 11:00 US Eastern time

Prehistoric bone tool ‘factory’ hints at early development of abstract reasoning in human ancestors

The oldest collection of mass-produced prehistoric bone tools reveal that human ancestors were likely capable of more advanced abstract reasoning one million years earlier than thought, finds a new study involving researchers at UCL and CSIC- Spanish National Research Council.

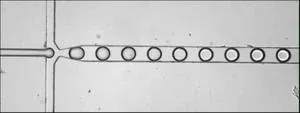

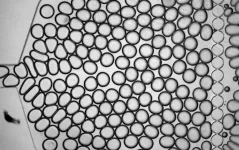

The paper, published in Nature, describes a collection of 27 now-fossilised bones that had been shaped into hand tools 1.5 million years ago by human ancestors.

It’s the earliest substantial collection of tools made from bone ever found, revealing that they were being systematically produced one million years earlier than archaeologists once thought.

Early human ancestors known as hominins (human ancestors who could walk upright) had already been making tools out of stone in some capacity for at least a million years, but there’s been scant evidence of widespread toolmaking out of bones before about 500,000 years ago.

The hominins who shaped the recently-discovered bone tools did so in a manner similar to how they made tools out of stone, by chipping away small flakes to create sharp edges – a process called ‘knapping’.

This transfer of techniques from one medium to another shows that the hominins who made the bone tools had an advanced understanding of toolmaking, and that they could adapt their techniques to different materials, a significant intellectual leap. It could indicate that human ancestors at that time possessed a greater level of cognitive skills and brain development than scientists thought.

Co-author Dr Renata F. Peters (UCL Archaeology) said: “The tools show evidence that their creators carefully worked the bones, chipping off flakes to create useful shapes. We were excited to find these bone tools from such an early timeframe. It means that human ancestors were capable of transferring skills from stone to bone, a level of complex cognition that we haven’t seen elsewhere for another million years.”

Lead author Dr Ignacio de la Torre of the CSIC-Spanish National Research Council added: “This discovery leads us to assume that early humans significantly expanded their technological options, which until then were limited to the production of stone tools and now allowed new raw materials to be incorporated into the repertoire of potential artifacts.

“At the same time, this expansion of technological potential indicates advances in the cognitive abilities and mental structures of these hominins, who knew how to incorporate technical innovations by adapting their knowledge of stone work to the manipulation of bone remains.”

The tools were discovered in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, a site renowned for its long history of important archaeological discoveries revealing the origins of humans.

The researchers found 27 bones that had been shaped into tools at the site. The bones mostly came from large mammals, mostly elephants and hippos. The tools are exclusively made from the animals’ limb bones, as these are the most dense and strong.

The tools originate from a time in prehistory where early hominin cultures were undergoing one of the first ever technological transitions.

The very earliest stone tools come from the “Oldowan” age which stretched from about 2.7 million years ago to 1.5 million years ago. It employs a simple method for making stone tools, by chipping one or a few flakes off a stone core using a hammerstone.

The bone tools reported in this study were from the time that the ancient human ancestors were progressing into the “Acheulean” age which began as far back as about 1.7 million years ago. The Acheulean technology is best characterised by the use of more intricate handaxes that were carefully shaped by knapping – allowing the production of tools through more standardised means.

The bone tools show that these more advanced techniques were carried over and adopted for use on bones as well, something previously unseen in the fossil record for another million years, much later into the Acheulean age.

Prior to this find, bones shaped into tools had only been identified sporadically in rare, isolated instances in the fossil record and never in a manner that implied that human ancestors were systematically producing them.

Though it’s unclear precisely what the tools were used for, because of their overall shape, size and sharp edges, it’s likely that they may have been employed to process animal carcasses for food.

It’s also unclear which species of human ancestor crafted the tools. No hominin remains were found alongside the collection of bone artefacts, though it’s known that, at the time, our human ancestor Homo erectus and another hominin species known as Paranthropus boisei were inhabitants of the region.

Because these tools were such an unexpected discovery, the researchers hope that their findings will prompt archaeologists to re-examine bone discoveries around the world in case other evidence of bone tools has been missed.

This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC).

Notes to Editors

For more information or to speak to the researchers involved, please contact Michael Lucibella, UCL Media Relations. T: +44 (0)75 3941 0389, E: m.lucibella@ucl.ac.uk

Ignacio de la Torre, Luc Doyon, Alfonso Benito-Calvo, Rafael Mora, Ipyana Mwakyoma, Jackson K. Njau, Renata F. Peters, Angeliki Theodoropoulou & Francesco d´Errico, ‘Systematic bone tool production at 1.5 million years ago’ will be published in Nature on Wednesday 5 March 2025, 16:00 UK time 11:00 US Eastern Time, and is under a strict embargo until this time.

The DOI for this paper will be https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08652-5

Additional material

Images and movies available for download at this link. Credit: CSIC

Dr Renata Peters’ academic profile

Dr Ignacio de la Torre’s academic profile

UCL Institute of Archaeology

UCL Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences

CSIC CSIC-Spanish National Research Council

About UCL – London’s Global University

UCL is a diverse global community of world-class academics, students, industry links, external partners, and alumni. Our powerful collective of individuals and institutions work together to explore new possibilities.

Since 1826, we have championed independent thought by attracting and nurturing the world's best minds. Our community of more than 50,000 students from 150 countries and over 16,000 staff pursues academic excellence, breaks boundaries and makes a positive impact on real world problems.

The Times and Sunday Times University of the Year 2024, we are consistently ranked among the top 10 universities in the world and are one of only a handful of institutions rated as having the strongest academic reputation and the broadest research impact.

We have a progressive and integrated approach to our teaching and research – championing innovation, creativity and cross-disciplinary working. We teach our students how to think, not what to think, and see them as partners, collaborators and contributors.

For almost 200 years, we are proud to have opened higher education to students from a wide range of backgrounds and to change the way we create and share knowledge.

We were the first in England to welcome women to university education and that courageous attitude and disruptive spirit is still alive today. We are UCL.

www.ucl.ac.uk | Follow @uclnews.bsky.social on Bluesky | Read news at www.ucl.ac.uk/news/ | Listen to UCL podcasts on SoundCloud | View images on Flickr | Find out what’s on at UCL Mind

END