(Press-News.org) Injuries to the articular cartilage in different joints, including the knee, are painful and limit mobility. Therefore, researchers at the University of Basel and University Hospital Basel are developing cartilage implants using cells from the patient’s nasal septum. A recent study shows that giving these cartilage implants more time to mature significantly improved clinical efficacy, even in patients with complex cartilage injuries. This suggests that the method could also be suitable for the treatment of degenerated cartilage in osteoarthritis.

An unlucky fall while skiing or playing football can spell the end of sports activities. Damage to articular cartilage does not heal by itself and increases the risk of osteoarthritis. Researchers at the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel have now shown that even complex cartilage injuries can be repaired with replacement cartilage engineered from cells taken from the nasal septum.

A team led by Professor Ivan Martin, Dr. Marcus Mumme and Professor Andrea Barbero has been developing this method for several years. It involves extracting the cells from a tiny piece of the patient’s nasal septum cartilage and then allowing them to multiply in the laboratory on a scaffold made of soft fibers. Finally, the newly grown cartilage is cut into the required shape and implanted into the knee joint.

Earlier studies have already shown promising results. “Nasal septum cartilage cells have particular characteristics that are ideally suited to cartilage regeneration,” explains Professor Martin. For example, it has emerged that these cells can counteract inflammation in the joints.

More mature cartilage shows better results

In a clinical trial involving 98 participants at clinics in four countries, the researchers compared two experimental approaches. One group received cartilage grafts that had matured in the lab for only two days before implantation – similar to other cartilage replacement products. For the other group, the grafts were allowed to mature for two weeks. During this time, the tissue acquires characteristics similar to native cartilage.

For 24 months after the procedure, the participants self-assessed their well-being and the functionality of the treated knee through questionnaires. The results, published in the scientific journal Science Translational Medicine, showed a clear improvement in both groups. However, patients who received more mature engineered cartilage continued to improve even in the second year following the procedure, overtaking the group with less mature cartilage grafts.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) further revealed that the more mature cartilage grafts resulted in better tissue composition at the site of the implant, and even of the neighboring cartilage. “The longer period of prior maturation is worthwhile,” emphasizes Anke Wixmerten, co-lead author of the study. The additional maturation time of the implant, she points out, only requires a slight increase in effort and manufacturing costs, and gives much better results.

Particularly suited to larger and more complex cartilage injuries

“It is noteworthy that patients with larger injuries benefit from cartilage grafts with longer prior maturation periods,” says Professor Barbero. This also applies, he says, to cases in which previous cartilage treatments with other techniques have been unsuccessful.

“Our study did not include a direct comparison with current treatments,” admits Professor Martin. “However, if we look at the results from standard questionnaires, patients treated with our approach achieved far higher long-term scores in joint functionality and quality of life.”

Based on these and earlier findings, the researchers at the Department of Biomedicine now plan to test this method for treating osteoarthritis – an inflammatory disease that causes joint cartilage degeneration, resulting in chronic pain and disability.

Two large-scale clinical studies, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the EU research framework program Horizon Europe, are about to begin. These studies will explore the technique’s effectiveness in treating a specific form of osteoarthritis affecting the kneecaps (i.e., patellofemoral osteoarthritis). The activities will further develop in Basel the field of cellular therapies, strategically defined as a priority area for research and innovation at the University of Basel and University Hospital Basel.

END

Engineered cartilage from nasal septum cells helps treat complex knee injuries

2025-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Damaged but not defeated: Bacteria use nano-spearguns to retaliate against attacks

2025-03-05

Some bacteria deploy tiny spearguns to retaliate against rival attacks. Researchers at the University of Basel mimicked attacks by poking bacteria with an ultra-sharp tip. Using this approach, they have uncovered that bacteria assemble their nanoweapons in response to cell envelope damage and rapidly strike back with high precision.

In the world of microbes, peaceful coexistence goes hand in hand with fierce competition for nutrients and space. Certain bacteria outcompete rivals and fend off attackers by injecting them with a lethal cocktail using tiny, ...

Among older women, hormone therapy linked to tau accumulation, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease

2025-03-05

A new study from Mass General Brigham researchers has found faster accumulation of tau—a key indicator of Alzheimer’s disease—in the brains of women over the age of 70 who took menopausal hormone therapy (HT) more than a decade before. Results, which are published in Science Advances, could help inform discussions between patients and clinicians about Alzheimer’s disease risk and HT treatment.

While the researchers did not see a significant difference in amyloid beta accumulation, they did find a significant difference in how fast regional tau accumulated in the brains of women over the age of 70, with women who had taken HT showing faster tau accumulation ...

Scientists catch water molecules flipping before splitting

2025-03-05

For the first time, Northwestern University scientists have watched water molecules in real-time as they prepared to give up electrons to form oxygen.

In the crucial moment before producing oxygen, the water molecules performed an unexpected trick: They flipped.

Because these acrobatics are energy intensive, the observations help explain why water splitting uses more energy than theoretical calculations suggest. The findings also could lead to new insights into increasing the efficiency of water splitting, a process that holds promise for generating clean hydrogen fuel and for producing breathable oxygen during future missions to Mars.

The study will be published Wednesday (March 5) ...

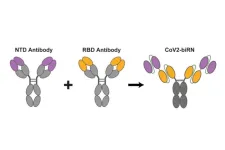

New antibodies show potential to defeat all SARS-CoV-2 variants

2025-03-05

The virus that causes COVID-19 has been very good at mutating to keep infecting people – so good that most antibody treatments developed during the pandemic are no longer effective. Now a team led by Stanford University researchers may have found a way to pin down the constantly evolving virus and develop longer-lasting treatments.

The researchers discovered a method to use two antibodies, one to serve as a type of anchor by attaching to an area of the virus that does not change very much and another to inhibit the virus’s ability ...

Mental health may be linked to how confident we are of our decisions

2025-03-05

A new study finds that a lower confidence in one’s judgement of decisions based on memory or perception is more likely to be apparent in individuals with anxiety and depression symptoms, whilst a higher confidence is more likely to be associated compulsivity, thus shedding light on the intricate link between cognition and mental health manifestations.

####

Article Title: Metacognitive biases in anxiety-depression and compulsivity extend across perception and memory

Author Countries: Germany, United Kingdom

Funding: TXFS is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow (224051/Z/21/Z) based at the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry ...

Research identifies key antibodies for development of broadly protective norovirus vaccine

2025-03-05

Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institutes of Health, have discovered a strategy to fight back against norovirus, a leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Their new study, published in Science Translational Medicine, identifies powerful antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide range of norovirus strains. The finding could lead to the design of broadly effective norovirus vaccine, as well as the development of new therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of norovirus-associated gastroenteritis.

Norovirus ...

NHS urged to offer single pill to all over-50s to prevent heart attacks and strokes

2025-03-05

The NHS could prevent thousands more heart attacks and strokes every year by offering everyone in the UK aged 50 and over a single “polypill” combining a statin and three blood pressure lowering drugs, according to academics from UCL.

In an opinion piece for The BMJ, the authors argued that a polypill programme could be a “flagship strategy” in Labour’s commitment to preventing disease rather than treating sickness. The programme would use age alone to assess eligibility, focusing on disease prevention rather than disease prediction.

They said such a strategy should replace the NHS Health Check, a five-yearly assessment ...

Australian researchers call for greater diversity in genomics

2025-03-05

A new study has uncovered that a gene variant common in Oceanian communities was misclassified as a potential cause of heart disease, highlighting the risk of the current diversity gap in genomics research which can pose a greater risk for misdiagnosis of people from non-European ancestries.

Led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and published in the European Heart Journal, the researchers describe the cases of two individuals of Pacific Island ancestries who carry a genetic variant previously thought to be a likely cause for their inherited ...

The pot is already boiling for 2% of the world’s amphibians: new study

2025-03-05

Scientists will be able to better identify what amphibian species and habitats will be most impacted by climate change, thanks to a new study by UNSW researchers.

Amphibians are the world’s most at-risk vertebrates, with more than 40% of species listed as threatened – and losing entire populations could have catastrophic flow-on effects.

Being ectothermic – regulating their body heat by external sources – amphibians are particularly vulnerable to temperature change in their habitats.

Despite this, the resilience of amphibians to rising temperatures ...

A new way to predict cancer's spread? Scientists look at 'stickiness' of tumor cells

2025-03-05

By assessing how “sticky” tumor cells are, researchers at the University of California San Diego have found a potential way to predict whether a patient’s early-stage breast cancer is likely to spread. The discovery, made possible by a specially designed microfluidic device, could help doctors identify high-risk patients and tailor their treatments accordingly.

The device, which was tested in an investigator-initiated trial, works by pushing tumor cells through fluid-filled chambers and sorting them based on how well they adhere to the chamber walls. When tested ...