(Press-News.org) Some bacteria deploy tiny spearguns to retaliate against rival attacks. Researchers at the University of Basel mimicked attacks by poking bacteria with an ultra-sharp tip. Using this approach, they have uncovered that bacteria assemble their nanoweapons in response to cell envelope damage and rapidly strike back with high precision.

In the world of microbes, peaceful coexistence goes hand in hand with fierce competition for nutrients and space. Certain bacteria outcompete rivals and fend off attackers by injecting them with a lethal cocktail using tiny, nano-sized spearguns, known as type VI secretion systems (T6SS).

Bacteria respond to cell envelope damage

The research group led by Professor Marek Basler at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has been studying the T6SS of different bacterial species for many years. “We knew that Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses its T6SS to fire back when attacked”, explains Basler. “But we did not know what exactly triggers the assembly of the nano-speargun: the contact with neighbors, toxic molecules, or simply cell damage?”

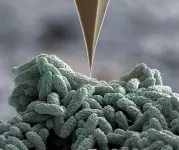

In close collaboration with Roderick Lim, Argovia Professor for Nanobiology at the Biozentrum and the Swiss Nanoscience Institute (SNI), the researchers have now demonstrated: Pseudomonas aeruginosa responds to ruptures in the outer membrane – initiated by mechanical force, such as poking with a sharp tip. The study has been published in Science Advances.

Puncturing bacterial envelope with a tiny “needle”

Roderick Lim’s lab has a long-standing expertise in atomic force microscopy (AFM) technology. “Using AFM, we have been able to mimic a bacterial T6SS attack”, says Mitchell Brüderlin, PhD student at the SNI PhD School and first-author of the study. “With the needle-like, ultra-sharp AFM tip, we can touch the bacterial surface and, with gradually increasing the pressure, puncture the outer and the inner membrane in a controlled manner.”

In combination with fluorescence microscopy, the researchers revealed that the bacteria respond to outer membrane damage. “Within ten seconds the bacteria assemble their T6SS, often repeatedly, at the site of damage and fire back with pinpoint accuracy,” adds Basler. “Our work clearly shows that breaking the outer membrane is necessary and sufficient to trigger T6SS assembly.”

New insights into bacterial defense mechanisms

The biggest challenge for the researchers was the size and the shape of the bacteria. “So far, we have only used the AFM to study eukaryotic cells, including human cells,” explains Lim. “But Pseudomonas bacteria are more than ten times smaller than human cells, so it was demanding to poke them at a specific site.”

In the microbial ecosystem, survival is all about strategy, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa has certainly mastered the art of defense. “The targeted and swift retaliation against local attacks minimizes misfiring and optimizes the cost-benefit ratio”, says Basler. This clever tactic gives Pseudomonas a survival advantage, enabling it to incapacitate attackers and thrive in diverse and often challenging environments.

END

Damaged but not defeated: Bacteria use nano-spearguns to retaliate against attacks

2025-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Among older women, hormone therapy linked to tau accumulation, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease

2025-03-05

A new study from Mass General Brigham researchers has found faster accumulation of tau—a key indicator of Alzheimer’s disease—in the brains of women over the age of 70 who took menopausal hormone therapy (HT) more than a decade before. Results, which are published in Science Advances, could help inform discussions between patients and clinicians about Alzheimer’s disease risk and HT treatment.

While the researchers did not see a significant difference in amyloid beta accumulation, they did find a significant difference in how fast regional tau accumulated in the brains of women over the age of 70, with women who had taken HT showing faster tau accumulation ...

Scientists catch water molecules flipping before splitting

2025-03-05

For the first time, Northwestern University scientists have watched water molecules in real-time as they prepared to give up electrons to form oxygen.

In the crucial moment before producing oxygen, the water molecules performed an unexpected trick: They flipped.

Because these acrobatics are energy intensive, the observations help explain why water splitting uses more energy than theoretical calculations suggest. The findings also could lead to new insights into increasing the efficiency of water splitting, a process that holds promise for generating clean hydrogen fuel and for producing breathable oxygen during future missions to Mars.

The study will be published Wednesday (March 5) ...

New antibodies show potential to defeat all SARS-CoV-2 variants

2025-03-05

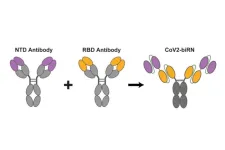

The virus that causes COVID-19 has been very good at mutating to keep infecting people – so good that most antibody treatments developed during the pandemic are no longer effective. Now a team led by Stanford University researchers may have found a way to pin down the constantly evolving virus and develop longer-lasting treatments.

The researchers discovered a method to use two antibodies, one to serve as a type of anchor by attaching to an area of the virus that does not change very much and another to inhibit the virus’s ability ...

Mental health may be linked to how confident we are of our decisions

2025-03-05

A new study finds that a lower confidence in one’s judgement of decisions based on memory or perception is more likely to be apparent in individuals with anxiety and depression symptoms, whilst a higher confidence is more likely to be associated compulsivity, thus shedding light on the intricate link between cognition and mental health manifestations.

####

Article Title: Metacognitive biases in anxiety-depression and compulsivity extend across perception and memory

Author Countries: Germany, United Kingdom

Funding: TXFS is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow (224051/Z/21/Z) based at the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry ...

Research identifies key antibodies for development of broadly protective norovirus vaccine

2025-03-05

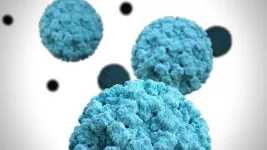

Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institutes of Health, have discovered a strategy to fight back against norovirus, a leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Their new study, published in Science Translational Medicine, identifies powerful antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide range of norovirus strains. The finding could lead to the design of broadly effective norovirus vaccine, as well as the development of new therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of norovirus-associated gastroenteritis.

Norovirus ...

NHS urged to offer single pill to all over-50s to prevent heart attacks and strokes

2025-03-05

The NHS could prevent thousands more heart attacks and strokes every year by offering everyone in the UK aged 50 and over a single “polypill” combining a statin and three blood pressure lowering drugs, according to academics from UCL.

In an opinion piece for The BMJ, the authors argued that a polypill programme could be a “flagship strategy” in Labour’s commitment to preventing disease rather than treating sickness. The programme would use age alone to assess eligibility, focusing on disease prevention rather than disease prediction.

They said such a strategy should replace the NHS Health Check, a five-yearly assessment ...

Australian researchers call for greater diversity in genomics

2025-03-05

A new study has uncovered that a gene variant common in Oceanian communities was misclassified as a potential cause of heart disease, highlighting the risk of the current diversity gap in genomics research which can pose a greater risk for misdiagnosis of people from non-European ancestries.

Led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and published in the European Heart Journal, the researchers describe the cases of two individuals of Pacific Island ancestries who carry a genetic variant previously thought to be a likely cause for their inherited ...

The pot is already boiling for 2% of the world’s amphibians: new study

2025-03-05

Scientists will be able to better identify what amphibian species and habitats will be most impacted by climate change, thanks to a new study by UNSW researchers.

Amphibians are the world’s most at-risk vertebrates, with more than 40% of species listed as threatened – and losing entire populations could have catastrophic flow-on effects.

Being ectothermic – regulating their body heat by external sources – amphibians are particularly vulnerable to temperature change in their habitats.

Despite this, the resilience of amphibians to rising temperatures ...

A new way to predict cancer's spread? Scientists look at 'stickiness' of tumor cells

2025-03-05

By assessing how “sticky” tumor cells are, researchers at the University of California San Diego have found a potential way to predict whether a patient’s early-stage breast cancer is likely to spread. The discovery, made possible by a specially designed microfluidic device, could help doctors identify high-risk patients and tailor their treatments accordingly.

The device, which was tested in an investigator-initiated trial, works by pushing tumor cells through fluid-filled chambers and sorting them based on how well they adhere to the chamber walls. When tested ...

Prehistoric bone tool ‘factory’ hints at early development of abstract reasoning in human ancestors

2025-03-05

UCL Press Release

Under embargo until Wednesday 5 March 2025, 16:00 UK time / 11:00 US Eastern time

Prehistoric bone tool ‘factory’ hints at early development of abstract reasoning in human ancestors

The oldest collection of mass-produced prehistoric bone tools reveal that human ancestors were likely capable of more advanced abstract reasoning one million years earlier than thought, finds a new study involving researchers at UCL and CSIC- Spanish National Research Council.

The paper, published in Nature, describes a collection of 27 now-fossilised bones that had been shaped into hand tools 1.5 million years ago by human ancestors.

It’s ...