(Press-News.org) Oxytocin, a hormone already known for its role in childbirth, milk release, and mother-infant bonding, may have a newfound purpose in mammalian reproduction. In times of maternal stress, the hormone can delay an embryo’s development for days to weeks after conception, a new study in rodents shows. According to the authors, the findings about so-called “diapause” may offer new insights into pregnancy and fertility issues faced by humans.

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health, the study explored diapause, in which an embryo temporarily stops growing early in its development before it attaches to the lining of its mother’s uterus, a key step leading to the formation of the placenta. Known to occur in species ranging from armadillos to giant pandas to seals, diapause is thought to have evolved to help expectant mothers preserve scarce resources (e.g., breast milk) by delaying birth until they have enough to successfully take care of their offspring.

Although recent studies have uncovered evidence that a form of diapause may occur in humans, the underlying mechanisms behind it have until now remained unclear.

The findings in mice showed that one type of stress that may cause diapause is milk production and release (lactation), as it requires a mother to expend bodily nutrients to both nursing, already-born pups and to those growing in the womb. The study revealed that the time between conception and birth (gestation) — typically 20 days for these animals – was delayed by about a week in pregnant rodents that were already nursing a litter.

Further, the research team showed that this delay was brought about by a rise in the production of oxytocin, levels of which are known to go up as a mother lactates. To confirm this role for the hormone, the researchers exposed mouse embryos in the lab to a single dose (either 1 microgram or 10 micrograms) of oxytocin, and found that even these small amounts delayed their implantation in the uterus by as much as three days. Beyond just pausing pregnancy, the team found that surges of the chemical large enough to that mimic the amounts and timing measured during nursing caused loss of pregnancy in the mice in nearly all cases.

“Our findings shed light on the role of oxytocin in diapause,” said study co-author Moses Chao, PhD, a professor in the Departments of Cell Biology, Neuroscience, and Psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “Because of this newfound connection, it is possible that abnormalities in the production of this hormone could play roles in infertility, premature or delayed birth, and miscarriage.”

A report on the findings is publishing online March 5 in the journal Science Advances in a special issue focused on women’s health.

In another part of the study, the team searched for a mechanism that would allow embryos to react to an oxytocin surge. They found that the hormone can bind to special proteins called receptors on the surface of a layer of cells known as the trophectoderm, which surrounds the early embryo and eventually forms the placenta.

Notably, mouse embryos that were genetically altered to disable oxytocin receptors lived long enough to implant into their mother’s placenta at much lower rates than normal embryos. This suggests that the ability to respond to oxytocin spikes, and therefore go into diapause, is somehow important for the developing pups’ survival, says Chao, who plans to examine this protective function in more detail.

“Despite being extremely common, infertility and developmental issues that can arise during pregnancy remain poorly understood and can have a lasting, devastating impact on parents and their children,” said study senior author Robert Froemke, PhD. “Having a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to these problems may allow experts to better address them in the future,” added Froemke, the Skirball Professor of Genetics in the Department of Neuroscience at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Also a professor in the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Froemke says that the researchers next plan to examine how cell growth gets turned back on after diapause. In addition, the team plans to explore how diapause may affect offsprings’ health and development after birth, and determine whether and how their discoveries can inform reproductive medicine.

Froemke cautions that while the study results are promising, mice and humans — while both mammals — have significant differences in their reproductive processes. He adds that the current investigation did not assess the role that other pregnancy-related hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, may play in diapause. Froemke is also a member of NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Institute for Translational Neuroscience.

Funding for the study was provided by National Institutes of Health grants T32MH019524, NS107616, and HD088411.

In addition to Moses and Froemke, other NYU Langone researchers involved in the study are Luisa Schuster, PhD; Habon Issa, PhD; Janaye Stephens, BS; Michael Cammer, MFA, MAT; Latika Khatri; Maria Alvarado-Torres; Jie Tong, PhD; Orlando Aristizábal, MPhil; Youssef Wadghiri, PhD; Sang Yong Kim, PhD; Catherine Pei-ju Lu, PhD; and Silvana Valtcheva, PhD. Jessica Minder, PhD, a former graduate student at NYU Langone and a current postdoctoral associate at the University of California, Berkeley, served as the study lead author.

###

About NYU Langone Health

NYU Langone Health is a fully integrated health system that consistently achieves the best patient outcomes through a rigorous focus on quality that has resulted in some of the lowest mortality rates in the nation. Vizient, Inc., has ranked NYU Langone the No. 1 comprehensive academic medical center in the country for three years in a row, and U.S. News & World Report recently placed nine of its clinical specialties among the top five in the nation. NYU Langone offers a comprehensive range of medical services with one high standard of care across six inpatient locations, its Perlmutter Cancer Center, and more than 300 outpatient locations in the New York area and Florida. With $14.2 billion in revenue this year, the system also includes two tuition-free medical schools, in Manhattan and on Long Island, and a vast research enterprise with over $1 billion in active awards from the National Institutes of Health.

Media Inquiries:

Shira Polan

Phone: 212-404-4279

shira.polan@nyulangone.org

END

Findings may advance understanding of infertility in mothers

Findings may advance understanding of infertility in mothers

2025-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Engineered cartilage from nasal septum cells helps treat complex knee injuries

2025-03-05

Injuries to the articular cartilage in different joints, including the knee, are painful and limit mobility. Therefore, researchers at the University of Basel and University Hospital Basel are developing cartilage implants using cells from the patient’s nasal septum. A recent study shows that giving these cartilage implants more time to mature significantly improved clinical efficacy, even in patients with complex cartilage injuries. This suggests that the method could also be suitable for the treatment of degenerated cartilage in osteoarthritis.

An unlucky fall while skiing or playing ...

Damaged but not defeated: Bacteria use nano-spearguns to retaliate against attacks

2025-03-05

Some bacteria deploy tiny spearguns to retaliate against rival attacks. Researchers at the University of Basel mimicked attacks by poking bacteria with an ultra-sharp tip. Using this approach, they have uncovered that bacteria assemble their nanoweapons in response to cell envelope damage and rapidly strike back with high precision.

In the world of microbes, peaceful coexistence goes hand in hand with fierce competition for nutrients and space. Certain bacteria outcompete rivals and fend off attackers by injecting them with a lethal cocktail using tiny, ...

Among older women, hormone therapy linked to tau accumulation, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease

2025-03-05

A new study from Mass General Brigham researchers has found faster accumulation of tau—a key indicator of Alzheimer’s disease—in the brains of women over the age of 70 who took menopausal hormone therapy (HT) more than a decade before. Results, which are published in Science Advances, could help inform discussions between patients and clinicians about Alzheimer’s disease risk and HT treatment.

While the researchers did not see a significant difference in amyloid beta accumulation, they did find a significant difference in how fast regional tau accumulated in the brains of women over the age of 70, with women who had taken HT showing faster tau accumulation ...

Scientists catch water molecules flipping before splitting

2025-03-05

For the first time, Northwestern University scientists have watched water molecules in real-time as they prepared to give up electrons to form oxygen.

In the crucial moment before producing oxygen, the water molecules performed an unexpected trick: They flipped.

Because these acrobatics are energy intensive, the observations help explain why water splitting uses more energy than theoretical calculations suggest. The findings also could lead to new insights into increasing the efficiency of water splitting, a process that holds promise for generating clean hydrogen fuel and for producing breathable oxygen during future missions to Mars.

The study will be published Wednesday (March 5) ...

New antibodies show potential to defeat all SARS-CoV-2 variants

2025-03-05

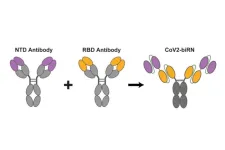

The virus that causes COVID-19 has been very good at mutating to keep infecting people – so good that most antibody treatments developed during the pandemic are no longer effective. Now a team led by Stanford University researchers may have found a way to pin down the constantly evolving virus and develop longer-lasting treatments.

The researchers discovered a method to use two antibodies, one to serve as a type of anchor by attaching to an area of the virus that does not change very much and another to inhibit the virus’s ability ...

Mental health may be linked to how confident we are of our decisions

2025-03-05

A new study finds that a lower confidence in one’s judgement of decisions based on memory or perception is more likely to be apparent in individuals with anxiety and depression symptoms, whilst a higher confidence is more likely to be associated compulsivity, thus shedding light on the intricate link between cognition and mental health manifestations.

####

Article Title: Metacognitive biases in anxiety-depression and compulsivity extend across perception and memory

Author Countries: Germany, United Kingdom

Funding: TXFS is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow (224051/Z/21/Z) based at the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry ...

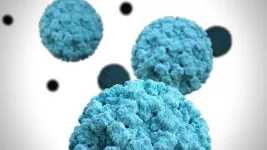

Research identifies key antibodies for development of broadly protective norovirus vaccine

2025-03-05

Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin, in collaboration with researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institutes of Health, have discovered a strategy to fight back against norovirus, a leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Their new study, published in Science Translational Medicine, identifies powerful antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide range of norovirus strains. The finding could lead to the design of broadly effective norovirus vaccine, as well as the development of new therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of norovirus-associated gastroenteritis.

Norovirus ...

NHS urged to offer single pill to all over-50s to prevent heart attacks and strokes

2025-03-05

The NHS could prevent thousands more heart attacks and strokes every year by offering everyone in the UK aged 50 and over a single “polypill” combining a statin and three blood pressure lowering drugs, according to academics from UCL.

In an opinion piece for The BMJ, the authors argued that a polypill programme could be a “flagship strategy” in Labour’s commitment to preventing disease rather than treating sickness. The programme would use age alone to assess eligibility, focusing on disease prevention rather than disease prediction.

They said such a strategy should replace the NHS Health Check, a five-yearly assessment ...

Australian researchers call for greater diversity in genomics

2025-03-05

A new study has uncovered that a gene variant common in Oceanian communities was misclassified as a potential cause of heart disease, highlighting the risk of the current diversity gap in genomics research which can pose a greater risk for misdiagnosis of people from non-European ancestries.

Led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and published in the European Heart Journal, the researchers describe the cases of two individuals of Pacific Island ancestries who carry a genetic variant previously thought to be a likely cause for their inherited ...

The pot is already boiling for 2% of the world’s amphibians: new study

2025-03-05

Scientists will be able to better identify what amphibian species and habitats will be most impacted by climate change, thanks to a new study by UNSW researchers.

Amphibians are the world’s most at-risk vertebrates, with more than 40% of species listed as threatened – and losing entire populations could have catastrophic flow-on effects.

Being ectothermic – regulating their body heat by external sources – amphibians are particularly vulnerable to temperature change in their habitats.

Despite this, the resilience of amphibians to rising temperatures ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

[Press-News.org] Findings may advance understanding of infertility in mothersFindings may advance understanding of infertility in mothers