(Press-News.org) Our brains use basic ‘building blocks’ of information to keep track of how people interact, enabling us to navigate complex social interactions, finds a new study led by University College London (UCL) researchers.

For the study, published in Nature, the researchers scanned the brains of participants who were playing a simple game involving a teammate and two opponents, to see how their brains were able to keep track of information about the group of players.

The scientists found that rather than keeping track of the performance of each individual player, specific parts of the participants’ brains would react to specific patterns of interaction, or ‘building blocks’ of information that could be combined to understand what was going on.

Lead author Dr Marco Wittmann (UCL Psychology & Language Sciences and Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research) said: “Humans are social creatures that are capable of keeping track of highly complex and fluid social dynamics, requiring a massive amount of brain power to remember not only individual people but also the various relationships between them.

“In order to keep up with a group social interaction in real time, our brains must be using heuristics – mental shortcuts that help people make decisions quickly – to compress and simplify the wealth of information involved, with a system that minimises complexity while still allowing flexibility and detail.

“In this research, we found that our brains appear to use a set of basic ‘building blocks’ that represent fundamental aspects of social interactions, enabling us to quickly figure out new and complex social situations.”

For the study, the team of scientists from UCL and the University of Oxford used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record the brain activity of 88 participants who were playing a simple game. While in the scanner, the study participants were given a series of information about how they, a partner, and their opponents were faring in a game, and needed to keep track of the information in order to answer a question comparing performances of different players.

Dr Wittmann explained: “We were interested to see whether our brains would use an ‘agent-centric’ frame of reference where specific parts of the brain keep track of each player’s performance, or a ‘sequential’ frame of reference tracking the information in the order it was received. We found that people actually do both, but our brains are able to simplify all of this information into bite-sized chunks.”

The scientists were able to pinpoint specific patterns of activity in the brain that represented a few specific ‘building blocks’, each representing a pattern of interaction between the players.

For example, one building block kept information about how well a participant and their partner were doing relative to the other team. A bigger difference in performance between the two teams corresponded to an increase in brain activity related to this building block. These specific patterns of activity were found in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision-making and social behaviour.

The researchers say these fundamental building blocks appear to represent patterns of interaction that are common to many different situations.

Dr Wittmann said: “As we develop social skills in life, our brains are likely learning specific interaction patterns that we come across again and again. These patterns may become hard-wired into our brains as building blocks that get assembled and recombined to construct our understanding of any social setting.”

END

How the brain uses ‘building blocks’ to navigate social interactions

2025-03-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Want to preserve biodiversity? Go big, U-M researchers say

2025-03-12

ANN ARBOR—Large, undisturbed forests are better for harboring biodiversity than fragmented landscapes, according to University of Michigan research.

Ecologists agree that habitat loss and the fragmentation of forests reduces biodiversity in the remaining fragments. But ecologists don't agree whether it's better to focus on preserving many smaller, fragmented tracts of land or larger, continuous landscapes. The study, published in Nature and led by U-M ecologist Thiago Gonçalves-Souza, comes to a conclusion on the decades-long debate.

"Fragmentation is bad," said study author Nate Sanders, U-M professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. ...

Ultra-broadband photonic chip boosts optical signals

2025-03-12

Modern communication networks rely on optical signals to transfer vast amounts of data. But just like a weak radio signal, these optical signals need to be amplified to travel long distances without losing information. The most common amplifiers, erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs), have served this purpose for decades, enabling longer transmission distances without the need for frequent signal regeneration. However, they operate within a limited spectral bandwidth, restricting the expansion of optical networks.

To meet the growing demand for high-speed data transmission, researchers have been seeking ways to develop more powerful, flexible, ...

Chinese scientists explain energy transfer mechanism in chloroplasts and its evolution

2025-03-12

A recent study by Chinese scientists has revealed the intricate molecular machinery driving energy exchange within chloroplasts, shedding light on a key event in the evolution of plant life. Led by FAN Minrui from the Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the research elucidates the structure and function of the ATP/ADP translocator—a crucial member of the nucleotide transporter (NTT) family of proteins—which facilitates the transfer of energy across chloroplast membranes.

Their findings were published online in ...

Exciting moments on the edge

2025-03-12

Scientists have long suspected that phosphorene nanoribbons (PNRs) – thin pieces of black phosphorus, only a few nanometres wide – might exhibit unique magnetic and semiconducting properties, but proving this has been difficult. In a recent study published in Nature, researchers focused on exploring the potential for magnetic and semiconducting characteristics of these nanoribbons. Using techniques such as ultrafast magneto-optical spectroscopy and electron paramagnetic resonance they were able to demonstrate the magnetic behaviour of PNRs at room temperature, and show how these magnetic properties can interact with light.

The ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights for March 12, 2025

2025-03-12

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Study offers insights into evolutionary process driving pancreatic cancer

Read summary | Read study in Nature

Pancreatic cancer is hard to treat because ...

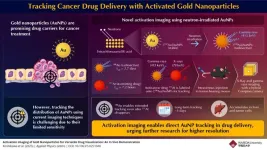

Lighting the way: how activated gold reveals drug movement in the body

2025-03-12

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are tiny gold particles of 1–100 nanometers and have unique chemical and biological properties. Due to their potential to accumulate in tumors, these nanoparticles have emerged as promising drug carriers for cancer therapy and targeted drug delivery. However, tracking the movement of these nanoparticles in the body has been a major challenge. Traditional imaging methods often involve tracers like fluorescent dyes and radioisotopes, which give limited visualization and inaccurate results due to detachment from AuNPs.

In a step to advance the imaging of AuNPs, researchers from Waseda ...

SwRI-led PUNCH constellation launches

2025-03-12

SAN ANTONIO — March 12, 2025 — Four small suitcase-sized spacecraft, designed and built by Southwest Research Institute headquartered in San Antonio, launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on March 11. NASA’s Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere, or PUNCH, constellation has spread out in a low-Earth orbit along the day-night line, providing a clear view in all directions for its two-year primary mission.

“The PUNCH spacecraft are now drifting into perfect position to study the solar corona, the Sun’s outer ...

Cells “speed date” to find their neighbors when forming tissues

2025-03-12

In developing hearts, cells shuffle around, bumping into each other to find their place, and the stakes are high: pairing with the wrong cell could mean the difference between a beating heart and one that falters. A study publishing on March 12 in the Cell Press journal Biophysical Journal demonstrates how heart cells go about this “matchmaking” process. The researchers model the intricate movements of these cells and predict how genetic variations could disrupt the heart development process in fruit flies.

In both humans and fruit flies, the heart’s tissues arise from two distinct regions of ...

Food insecurity today, heart disease tomorrow?

2025-03-12

Study compares those with food insecurity to food-secure individuals over 20 years

Food insecurity is associated with a 41% increased risk of heart disease over time

Findings suggest food security screening as a key tool to prevent heart disease

CHICAGO --- Struggling to afford food today could mean heart problems tomorrow. Young adults experiencing food insecurity have a 41% greater risk of developing heart disease in midlife, even after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic factors, according to a new Northwestern Medicine study. Food insecurity — struggling to get enough nutritious ...

Food insecurity and incident cardiovascular disease among Black and White US individuals

2025-03-12

About The Study: In this prospective cohort study among participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, food insecurity was associated with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) even after adjustment for socioeconomic factors, suggesting that food insecurity may be an important social deprivation measure in clinical assessment of CVD risk. Whether interventions to reduce food insecurity programs can potentially alleviate CVD should be further studied.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Jenny Jia, MD, MSc, email jenny.jia@northwestern.edu.

To access the embargoed study: ...