(Press-News.org) When someone is traumatically injured, giving them blood products before they arrive at the hospital – such as at the scene or during emergency transport – can improve their likelihood of survival and recovery. But patients with certain traumatic injuries have better outcomes when administered specific blood components.

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC scientist-surgeons announced today in Cell Reports Medicine that giving plasma that has been separated from other parts of donated blood improves outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) or shock, whereas giving unseparated or “whole” blood may be best for patients with traumatic bleeding.

Together, Pitt and UPMC have become home to the largest clinical trials research consortium for early trauma care in the U.S., with significant funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, allowing the research to benefit both soldiers and civilians.

“We’ve heard about precision medicine – giving the right care to the right patient at the right time. This is precision transfusion – giving the right blood product to the right patient at the right time,” said senior author Timothy Billiar, M.D., George Vance Foster Professor and Chair of Pitt’s Department of Surgery and chief scientific officer at UPMC. “We’re not just replacing the blood – it’s almost like a drug where we’re maximizing its benefits and minimizing side effects.”

The discovery was made with the Shock, Whole Blood, and Assessment of TBI (SWAT) multicenter study, co-led by co-senior author Jason Sperry, M.D., M.P.H., section chief of trauma surgery at Pitt, as well as co-authors Francis X. Guyette, M.D., professor of emergency medicine at Pitt and medical director for STAT MedEvac, and Stephen R. Wisniewski, Ph.D., epidemiology professor and associate vice chancellor for clinical trials coordination at Pitt.

SWAT enrolled over 1,000 traumatically injured patients with a high probability of needing emergency surgery and sampled their blood at set timepoints. A subset of 134 patients with multiple blunt or penetrating injuries who received at least one unit of blood product (red blood cells, plasma, platelets or whole blood) before hospital admission were further studied.

After applying computational methods to ensure that their findings were not skewed by age, gender or other confounding factors, the team found that receiving a higher proportion of plasma – alone or in conjunction with whole blood – before arriving at the hospital was associated with improved coagulation in patients with severe shock and TBI markers, and reduced post-admission transfusion volumes in patient with TBI.

“To me, that was the ‘Eureka!’ moment,” Billiar said. “Because, hey, wait a minute, plasma is part of whole blood, so why is just giving plasma better?”

Plasma is the protein-rich portion of blood, so the team then took a deep dive into proteomics – the study of proteins, which are complex molecules produced by cells that are essential for the structure and function of organs and tissues. They tested for more than 7,500 proteins in healthy donor blood and that of the trauma patients as they progressed through recovery and found clear differences. They then narrowed their list of proteins to 198 with well-known roles in inflammatory and clotting processes following traumatic injury.

Patients who received plasma had a distinct proteomic profile compared to those who did not, suggesting that receiving plasma had an impact on the proteins that help with inflammation and clotting. In particular, plasma recipients had higher levels of proteins associated with later stages of clot formation, neuron survival, platelet function, wound repair and inflammation mediation.

However, since the amount of plasma in a unit of whole blood is approximately the same as the amount of plasma that would be given individually as a separate blood product, it is still unclear why patients who received the separated plasma fared better and had proteomic profiles more conducive to healing.

“There are differences in the storage time of whole blood and plasma – whole blood can be kept for 21 days, whereas plasma alone has a five-day shelf life. Perhaps when kept in whole blood the proteins in the plasma change over time, possibly because the blood cells release enzymes that act on the plasma proteins,” said Sperry, who is also the Andrew B. Peitzman Professor of Surgery at Pitt. “The proteomic profile of different donors likely varies as well from person-to-person. As we consider a strategy to leverage our findings to improve patient outcomes, it will be important to untangle this mystery.”

Sperry noted that it isn’t practical for most ambulances to carry plasma, since it expires so quickly and would result in a lot of wasted plasma for all but the busiest ambulance services, and must be kept refrigerated, making it logistically difficult to transport.

“Our findings indicate that it is worthwhile to overcome these challenges,” Sperry said. “Getting the right blood products to the right patient at the right time is a life-saving endeavor and I’m confident we’ll continue to lead innovations that make it possible.”

Additional authors on this research are Hamed Moheimani, M.D., M.P.H., Xuejing Sun, M.D., Mehves Ozel, M.D., Jennifer L. Darby, M.D., Erika P. Ong, M.D., Tunde Oyebamiji, M.D., Upendra K. Kar, Ph.D., Mark H. Yazer, M.D., Matthew D. Neal, M.D., and Jishnu Das, Ph.D., all of Pitt; Bryan A. Cotton, M.D., M.P.H., of the University of Texas Health Science Center; Jeremy W. Cannon, M.D., of the University of Pennsylvania; Martin A. Schreiber, M.D., of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Ernest E. Moore, M.D., of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center; Nicholas Namias, M.D., of the University of Miami; Joseph P. Minei, M.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; and Christopher D. Barrett, M.D., of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

This research was supported by Department of Defense contract no. W81XWH-16-D-0024, task order W81XWH-16-D-0024-0002.

END

Trauma surgeons propose ‘precision transfusion’ approach to pre-hospital care

2025-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New artificial intelligence tool accelerates disease treatments

2025-03-18

University of Virginia School of Medicine scientists have created a computational tool to accelerate the development of new disease treatments. The tool goes beyond current artificial intelligence (AI) approaches by identifying not just which patient populations may benefit but also how the drugs work inside cells.

The researchers have demonstrated the tool’s potential by identifying a promising candidate to prevent heart failure, a leading cause of death in the United States and around the world.

The new AI tool called LogiRx, can predict how drugs will affect biological processes in the body, helping scientists understand the effects the drugs will have ...

CCA appoints expert panel on enhancing national research infrastructure

2025-03-18

Canada’s research infrastructure is essential to the future of science and innovation, economic prosperity, and well-being throughout the country. At the request of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada, the CCA has formed an expert panel to support the federal government in optimizing Canada’s research infrastructure—from its national-scale scientific facilities to its digital platforms and collaborative networks—through evidence synthesis and strategic insights. Janet King, Chair of Polar Knowledge Canada’s Board of Directors and Vice-Chair of the Canadian Light Source’s Board of Directors, will serve ...

Rising Stars: PPPL researchers honored in 2024 Physics of Plasmas Early Career Collection

2025-03-18

Celebrating fresh thinking in plasma physics is essential to the continued growth of the field, and this year’s Physics of Plasmas Early Career Collection highlights some of the most promising new voices pushing the boundaries of discovery.

The prestigious collection highlights top papers from all areas of plasma physics research authored by individuals who defended their dissertations within the past five years. This year, three researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) are featured in the Early Career Collection:

Staff Research ...

Add some spice: Curcumin helps treat mycobacterium abscessus

2025-03-18

Highlights:

Mycobacterium abscessus can cause dangerous lung infections.

Treatment usually requires a combination of antibiotics for more than a year.

Researchers in China report that curcumin, found in turmeric, can enhance treatment with bedaquiline, an antimycobacterial.

Animal studies showed that treatment with the combination led to a faster clearance of the infection.

Washington, D.C.—Mycobacterium abscessus is a fast-growing, pathogenic mycobacteria that can cause lung infections, and people who have respiratory conditions or are immunocompromised ...

Coastal guardians pioneer a new way to protect the Florida Keys’ shorelines

2025-03-18

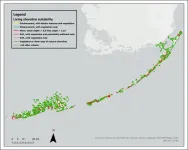

By 2050, sea levels along the United States coast are expected to rise by 0.25 to 0.30 meters, increasing flooding in low-lying areas. Due to its unique geography and infrastructure network, the Florida Keys is particularly at risk of climate hazards such as sea level rise, hurricanes and flooding. Since 2015, the Florida Keys has experienced four hurricanes – Irma (2107), Ian (2022), Helene (2024) and Milton (2024).

Nature-based solutions, such as restoring mangroves and coastal strands, can help mitigate these risks by stabilizing shorelines, improving ecosystems ...

Study shows rise in congenital heart defects in states with restrictive abortion laws

2025-03-18

The incidence of babies born with serious heart defects, known as cyanotic congenital heart disease (CCHD), rose in states that enacted restrictive abortion laws following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling that put abortion laws in the hands of the states, according to a study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

The study is the first to look at rates of congenital heart defects since the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ...

Healthy plant-based foods could help people with cardiometabolic disorders live longer

2025-03-18

People with cardiometabolic disorders—such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease—could increase their chances of living longer by adopting a healthy plant-based diet, according to a study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

While previous studies have assessed the benefits of plant-based diets in a general population, this new study is the first to focus on their benefits in people with cardiometabolic disorders, which are rising in prevalence worldwide and bring an increased risk of premature death.

“Among populations with cardiometabolic disorders, ...

Cannabis users face substantially higher risk of heart attack

2025-03-18

Marijuana is now legal in many places, but is it safe? Two new studies add to mounting evidence that people who use cannabis are more likely to suffer a heart attack than people who do not use the drug, even among younger and otherwise healthy adults. The findings are from a retrospective study of over 4.6 million people published in JACC Advances and a meta-analysis of 12 previously published studies being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

Marijuana use has risen in the United States, especially in states where it is legal to buy, sell and ...

Lifestyle risks weigh heavier on women’s hearts

2025-03-18

Lifestyle and health factors that are linked with heart disease appear to have a greater impact on cardiovascular risk in women than men, according to a study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

While factors such as diet, exercise, smoking and blood pressure have long been linked with heart disease risk, the new study is the first to show that these associations are collectively stronger in women than men. According to the researchers, the ...

Plastic-degrading enzymes from landfills

2025-03-18

Enzymes found in landfills around the world may be able to break down plastic waste. Some 11 billion metric tons of plastic are projected to accumulate in the environment by 2050. Enzymatic and microbial degradation is a promising method of plastic recycling. Landfills, environments where plastics are an abundant resource, are crucibles of bacterial evolution. Liyan Song and colleagues collected plastic biocatalytic enzymes from landfills around the world, using metagenomics and machine learning. Samples came from China, Italy, Canada, Great Britain, Jamaica, and India and included refuse, leachate, sludge, and airborne particles. The authors identified 31,989 possible ...