Nature-based solutions, such as restoring mangroves and coastal strands, can help mitigate these risks by stabilizing shorelines, improving ecosystems and enhancing resilience to flooding and hurricanes. These solutions, alongside hybrid approaches and soft armoring, which uses natural materials like plants, sand dunes, or rocks to protect shorelines from erosion, offer effective, site-specific protection.

While living shorelines are beneficial, they require careful design and planning to optimize their effectiveness.

Researchers from Florida Atlantic University, in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, created a new tool to identify the most effective shoreline stabilization methods to prevent erosion and protect the Florida Keys from damage caused by natural forces like waves, tides and storms. Maintaining the shape and integrity of the shoreline reduces the risk of further erosion while protecting ecosystems, properties and infrastructure.

The goal is to guide decisions on using vegetated shorelines or combining them with structures to reduce waves, prevent erosion and protect Florida Keys communities from storms.

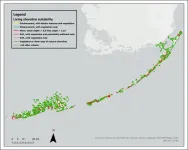

Results of the study, published in the Journal of Marine Science Engineering, reveal that nearly 8% of the approximately 2,550 kilometers of shoreline in the Florida Keys is suitable for nature-based solutions – mangrove planting, oyster reefs and beach dune vegetation – or hybrid solutions – some combination of hard structures and vegetation. Conversely, roughly 25.1% of the Florida Keys shoreline was deemed unsuitable for nature-based approaches, and approximately 67% is already vegetated or represents some other type of natural shoreline.

For the study, researchers designed a GIS-based multi-criteria decision tool that facilitates coastal restoration and integrates nature-based solutions into conventional shoreline armoring. They combined spatial analysis tools with expert input to develop a weighted suitability score for various types of shoreline reinforcement where feasible. By integrating data on existing shoreline types – sourced from an updated version of NOAA’s NOS Environmental Sensitivity Index – along with wind and wave exposure and physical environmental factors, they generated a composite Shoreline Relative Exposure Index. Based on this assessment, broadly defined categories of project types were recommended for various combinations of shoreline features and flood risk conditions.

Experts who completed the survey covered coastal engineering, stormwater management, marine biology, habitat restoration, community resilience, urban planning and sustainability. The data was used to calculate scores, which were analyzed through a machine-learning model to identify the best stabilization options for different shoreline types, including developed, undeveloped and protected areas.

Findings indicate that while conventional seawall armoring is needed in some areas of the Florida Keys coastline, hybrid and living shorelines should be prioritized where possible to protect people, habitats and resources. This requires involvement from private stakeholders and coordination among public entities to strengthen coastal resilience.

“Implementing innovative shoreline stabilization methods is crucial as environmental shifts and population growth are expected to exacerbate flood management challenges, making it essential to adopt sustainable, nature-based solutions that enhance resilience and protect vulnerable communities,” said Diana Mitsova, Ph.D., senior author and chair and professor of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning within FAU’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Science.

South Florida’s coastal ecosystems, including mangrove swamps and coastal strands, have already been incorporated into various shoreline management practices that reduce erosion potential and create appropriate habitat conditions. Mangroves are essential for sustaining estuarine and marine ecosystems in South Florida, providing critical habitat, stabilizing shorelines and supporting biodiversity. They offer nesting spots for many species and help the marine food chain by being a main source of small bits of organic matter. Their complex root systems keep the soil in place, reduce water cloudiness and help collect debris and particles in the water.

“New improvements in geospatial technology now allow us to combine human-made impact data with local land and ocean environmental data across large areas,” said Chris Bergh, field program director at The Nature Conservancy. “This information helps coastal managers identify key areas that need protection or are important for commercial and recreational activities. By doing this, it can help avoid conflicts between different uses of the coast and create a more flexible, forward-thinking and sustainable way of managing the area.”

The data from this study can be accessed through The Nature Conservancy’s Coastal Resilience, an online tool that uses GIS technology to help users visualize proposed shoreline stabilization methods tailored to different areas of the Florida Keys. It also allows users to overlay local data, like projected sea level rise, coastal habitats and land use.

Study co-authors are Kevin Cresswell, Ph.D., an adjunct faculty in the FAU Department of Urban and Regional Planning; Melina Matos, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the FAU Department of Urban and Regional Planning; Stephanie Wakefield, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the FAU Department of Urban and Regional Planning; Kathleen Freeman, GIS specialist, The Nature Conservancy; and William Carlos Lima, Ph.D., an adjunct faculty in FAU Department of Urban and Regional Planning.

- FAU -

About Florida Atlantic University:

Florida Atlantic University, established in 1961, officially opened its doors in 1964 as the fifth public university in Florida. Today, Florida Atlantic serves more than 30,000 undergraduate and graduate students across six campuses located along the Southeast Florida coast. In recent years, the University has doubled its research expenditures and outpaced its peers in student achievement rates. Through the coexistence of access and excellence, Florida Atlantic embodies an innovative model where traditional achievement gaps vanish. Florida Atlantic is designated as a Hispanic-serving institution, ranked as a top public university by U.S. News & World Report, and holds the designation of “R1: Very High Research Spending and Doctorate Production” by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Florida Atlantic shares this status with less than 5% of the nearly 4,000 universities in the United States. For more information, visit www.fau.edu.

END