(Press-News.org) By Leah Shaffer

The cells in human bodies are subject to both chemical and mechanical forces. But up until recently, scientists have not understood much about how to manipulate the mechanical side of that equation. That’s about to change.

“This is a major breakthrough in our ability to be able to control the cells that drive fibrosis,” according to Guy Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, speaking of research recently published in Nature Materials.

Fibrosis is an affliction wherein cells produce excess fibrous tissue. Fibroblast cells do this to close wounds, but the process can cascade in unwanted places. Examples include cardiac fibrosis; kidney or liver fibrosis, which precedes cancer; and pulmonary fibrosis, which can cause major scarring and breathing difficulties. Every soft tissue in the human body, even the brain, has the potential for cells to start going through a wound-healing cascade when they’re not supposed to, according to Genin.

The problem has both chemical and mechanical roots, but mechanical forces seem to play an outsized role. WashU researchers sought to harness the power of these mechanical forces, using a strategic pull and tug in the right mix of directions to tell the cell to shut off its loom of excess fiber.

In the newly published research, Genin and colleagues outline some of those details including how to intervene in tension fields at the right time to control how cells behave.

“The direction of the tension these cells apply matters a lot in terms of their activation state,” said Nathaniel Huebsch, associate professor of biomedical engineering at McKelvey, senior author of the research, along with Genin and Vivek Shenoy at the University of Pennsylvania.

The forces

The human body is constantly in motion, so it should come as no surprise that force can encode function in cells. But what forces, how much force and which direction are some of the questions that the Center for Engineering MechanoBiology examines.

“The magnitude of tension will affect what the cell does,” Huebsch said. But tension can go in many different directions. “The discovery that we present in this paper is that the way stress pulls in different directions makes a difference with the cell,” he added.

Pulling in multiple directions in a nonuniform manner, called tension anisotropy (imagine a taffy pull) is a key force in kicking off fibrosis, the researchers found.

“We’re showing, for the first time, using a structure with a tissue, we’re able to stop cell cytoskeletons from going down a pathway that will cause contraction and eventual fibrosis,” Genin said.

Huebsch, who pioneered microscopic models and scaffolds for testing these tension fields that act on cells, explained that tentacle-like microtubules establish tension by emerging and casting out in a direction. Collagen around the cell pulls back on that tubule and becomes aligned with it.

“We discovered that if you could disrupt the microtubules, you would disrupt that whole organization and you would potentially disrupt fibrosis,” said Huebsch.

And, though this research was about understanding what goes wrong to cause fibrosis, there is still much to learn about what goes right with fibroblasts, our connective tissue cells, especially in the heart, added Huebsch.

“In tissues where fibroblasts are typically well aligned, what is stopping them from activating to that wound healing state?” Huebsch asked.

Personalized treatment plans

Along with finding ways to prevent or treat fibrosis, Genin and Huebsch said doctors can look for ways to apply this new knowledge about the importance of mechanical stress to treatment of injuries or burns. The findings could help address the high fail rate for treatments of elderly patients with injuries that require reattaching tendon to bone or skin to skin.

For instance, in rotator cuff injuries, there is compelling evidence that patients must start moving their arm to recover function, but equally compelling evidence that patients should immobilize the arm for better recovery. The answer might depend on the amount of collagen a patient produces and the stress fields at play at the recovery site.

By understanding the multidirectional stress fields’ impact on the cell structure, doctors may be able to look at specific patients’ repair and determine a personalized treatment plan.

For instance, a patient who has biaxial stress coming from two directions at the site of injury will potentially need to exercise more to trigger cell repair, Genin said. However, another patient showing signs of uniaxial stress, meaning stress is pulling only one direction, any movement could over-activate cells, so in that case, the patient should keep the injury immobilized. All that and more is still to be worked out and confirmed but Genin is excited to begin.

“The next generation of disease we’re going to be conquering are diseases of mechanics,” Genin said.

Alisafaei F, Shakiba D, Hong Y, Ramahdita G, Huang Y, Iannucci LE, Davidson MD, Jafari M, Qian J, Qu C, Ju D, Flory DR, Huang Y-Y, Gupta P, Singamaneni S, Pryse KM, Chao PG, Burdick JA, Lake SP, Elson EL, Huebsch N, Shenoy VB, Genin GM. Tension anisotropy drives fibroblast phenotypic transition by self-reinforcing cell–extracellular matrix mechanical feedback. Nature Materials, online March 24, 2025.

DOI: https:// https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02162-5

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Center for Engineering

Mechanobiology grant CMMI-154857 (G.M.G, V.B.S., and J.A.B.), National Cancer Institute awards R01CA232256 (V.B.S.) and U54CA261694 (V.B.S.), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering awards R01EB017753 (V.B.S.) and R01EB030876 (V.B.S.), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases award R01AR077793 (G.M.G.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute award R01HL159094 (N.H), and National Science Foundation grants MRSEC/DMR-1720530 (V.B.S. and J.A.B.) and DMS-1953572 (V .B.S.).

END

The right moves to reign in fibrosis

WashU sets stage for medical treatments via mechanical forces

2025-03-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Exploring why it is harder to hear in noisy environments

2025-03-24

Imagine trying to listen to a friend speak over the commotion of a loud party. It is difficult to detect and process sounds in noisy environments, especially for those with hearing loss. Previous research has typically focused on how competing sounds influence cortical brain activity, with the end goal of informing treatment strategies for people who are hard of hearing. But in a new eNeuro study, Melissa Polonenko and Ross Maddox, from the University of Rochester, explored a lesser-studied influence of competing sounds on subcortical brain ...

Type 2 diabetes may suppress reward

2025-03-24

The high comorbidity of type 2 diabetes (T2D) with psychiatric or neurodegenerative disorders points to a need for understanding what links these diseases. A potential link is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The ACC supports behaviors related to cognition and emotions and is involved in some T2D-associated diseases, like mood disorders and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). James Hyman and colleagues, from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, used a rat model of T2D that affects only males to explore whether diabetes affects ACC activity and behavior. Their work is featured in JNeurosci’s ...

Healthy eating in midlife linked to overall healthy aging

2025-03-24

Embargoed for release: Monday, March 24, 12:00 PM ET

Key points:

Maintaining a healthy diet rich in plant-based foods, with low to moderate intake of healthy animal-based foods and lower intake of ultra-processed foods, was linked to a higher likelihood of healthy aging—defined as reaching age 70 free of major chronic diseases, with cognitive, physical, and mental health maintained—according to a 30-year study of food habits among more than 105,000 middle-aged adults.

All the eight dietary patterns studied were associated with healthy aging, suggesting that there is no one-size-fits-all healthy diet.

The study is among the ...

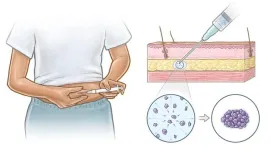

New non-surgical contraceptive implant is delivered through tiny needles

2025-03-24

Mass General Brigham and MIT investigators have developed a long-acting contraceptive implant that can be delivered through tiny needles to minimize patient discomfort and increase the likelihood of medication use.

Their findings in preclinical models provide the technological basis to develop self-administrable contraceptive shots that could mimic the long-term drug release of surgically implanted devices.

The new approach, which would reduce how often patients need to inject themselves and prove valuable for patients with less access to hospitals and other medical care ...

Motion sickness brain circuit may provide new options for treating obesity

2025-03-24

Motion sickness is a very common condition that affects about 1 in 3 people, but the brain circuits involved are largely unknown. In the current study published in Nature Metabolism, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital describe a new brain circuit involved in motion sickness that also contributes to regulating body temperature and metabolic balance. The findings may provide unconventional strategies ...

New research reveals secrets about locust swarm movement

2025-03-24

MEDIA INQUIRES

WRITTEN BY

Laura Muntean

Adam Russell

laura.muntean@ag.tamu.edu

601-248-1891

FOR ...

Age-specific trends in pediatric and adult firearm homicide after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

2025-03-24

About The Study: This study found a disproportionate spike in firearm homicide among children and adults older than age 30 after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating a change in the association between age and firearm victimization risk. This trend moved the peak victimization risk from age 21 to 19, and rates for children up to age 16 were markedly elevated. These age-specific patterns were most pronounced in later post-onset years.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Jonathan ...

Avoidable mortality across US states and high-income countries

2025-03-24

About The Study: This study found that avoidable mortality (comprising both preventable deaths related to prevention and public health and treatable deaths related to timely and effective health care treatment) has worsened across all U.S. states, while other high-income countries show improvement. The results suggest poorer mortality is driven by broad factors across the entirety of the U.S. While other countries appear to make gains in health with increases in health care spending, such an association does not exist across U.S. states, raising questions regarding U.S. health spending efficiency.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Irene ...

Breastfeeding duration and child development

2025-03-24

About The Study: Exclusive or longer duration of breastfeeding was associated with reduced odds of developmental delays and language or social neurodevelopmental conditions in this cohort study. These findings may guide parents, caregivers, and public health initiatives in promoting early child development.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Inbal Goldshtein, PhD, email inbal@kinstitute.org.il.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.1540)

Editor’s Note: Please see the ...

How chromosomes shape up for cell division

2025-03-24

Among the many marvels of life is the cell’s ability to divide and thus enable organisms to grow and renew themselves. For this, the cell must duplicate its DNA – its genome – and segregate it equally into two new daughter cells. To prepare the 46 chromosomes of a human cell for transport to the daughter cells during cell division, each chromosome forms a compact X-shaped structure with two rod-like copies. How the cell achieves this feat remains largely unknown.

Now, for the first time, EMBL scientists have directly observed this process in high resolution under the microscope ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] The right moves to reign in fibrosisWashU sets stage for medical treatments via mechanical forces