(Press-News.org)

Congenital hearing loss refers to impaired auditory function that occurs due to genetic causes. GJB2 is the gene responsible for approximately half of all cases of hereditary hearing loss. Connexin 26 (CX26), which is encoded by GJB2, helps in the formation of intercellular gap junctions—channels that allow for the movement of ions and chemical messenger molecules between adjacent cells, where it regulates auditory function.

GJB2 mutations often lead to fragmentation of gap junctions and gap junction plaques (GJPs) which are composed of CX26. While the inheritance of recessive GJB2 mutation containing two copies of the defective gene can be functionally cured via GJB2 gene replacement, GJB2 dominant-negative mutation where the mutant protein inhibits the normal functioning of the wild-type protein necessitates a gene editing approach.

In this light, researchers from Japan have successfully developed a gene therapy to repair R75W, a dominant-negative mutation of GJB2 that causes syndromic hearing loss. The research team included Associate Professor Dr. Kazusaku Kamiya and Assistant Professor Dr. Takao Ukaji in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine, Japan, and Dr. Osamu Nureki from the Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Japan. Their research findings were published in Volume 10, Issue 5 of JCI Insight on March 10, 2025.

“The overwhelming majority of mutations causing hereditary hearing loss involve the GJB2 gene. However, treatments that can restore hearing in patients with genetic deafness are lacking,” shares Dr. Kamiya. “Our research can contribute to the development of gene therapy to tackle the increasing incidence of hereditary hearing loss patients.”

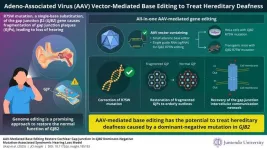

First, the researchers developed an AAV (AAV-Sia6e) that can deliver genome editing tools to a wide range of inner ear cells that form gap junctions. AAV is a useful vector for delivering genes; however, the size of the gene that can be carried is limited. Therefore, Dr. Kamiya and his team constructed a base editing tool (SaCas9-NNG-ABE8e) that was miniaturized to a size that can be carried by AAV using SaCas9-NNG, which has a smaller size and higher genome editing efficiency than conventional Cas9. Next, they loaded this base editing tool onto AAV-Sia6e, which has high infection tropism for inner ear cells and developed an all-in-one AAV vector for inner ear genome editing.

Genome editing via the all-in-one AAV vector showed considerable efficiency and specificity. It showed on-target T to C conversion in human cells, expressing the GJB2 R75W mutation, repaired the R75W mutation, and formed a clear GJP. Furthermore, after the base editing procedure, the physiological function of gap junction cell-cell communication was restored.

Finally, to validate their results, the researchers performed AAV-mediated genome editing in a transgenic mouse model with the GJB2 R75W mutation. Inner sulcus cells of the cochlea, which were infected with the all-in-one AAV vector, formed distinct GJPs with pentagonal or hexagonal structures arranged around cells that were similar to those observed in wild-type cells.

“By using an all-in-one AAV vector with high infectivity for the inner ear, we expect to improve the therapeutic effect, simplify the development process, and reduce costs. Furthermore, the ABE-based gene editing approach is expected to be less toxic and safer than the conventional CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The AAV genome editing therapy we developed can also be applied to the treatment of other genes that cause hearing loss,” concludes Dr. Kamiya, elaborating on the potential implications of the research.

Taken together, these findings highlight the immense therapeutic potential of the AAV-mediated genome editing approach for treating hereditary hearing loss.

Reference

Authors

Takao Ukaji1, Daisuke Arai1, Harumi Tsutsumi1, Ryoya Nakagawa2, Fumihiko Matsumoto1, Katsuhisa Ikeda1, Osamu Nureki2, and Kazusaku Kamiya1

Title of original paper

AAV-mediated base editing restores cochlear gap junction in GJB2

dominant-negative mutation-associated syndromic hearing loss model

Journal

JCI Insight

DOI

10.1172/jci.insight.185193

Affiliations

1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

2Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

About Associate Professor Dr. Kazusaku Kamiya

Dr. Kazusaku Kamiya is an Associate Professor at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine, Japan. He specializes in ear diseases with expertise in areas such as stem cells, hearing loss, gap junction, mutation, and cell therapy. He is also the Representative Director and CEO of Gap Junction Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Kamiya has over 50 publications and over 1,080 citations to his credit.

END

Molecular biologist Yali Dou, PhD, holder of the Marion and Harry Keiper Chair in Cancer Research and professor of medicine and cancer biology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, has been elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). She is one of seven USC faculty members in the 2025 cohort of new fellows.

The AAAS is the world’s oldest and largest general science organization and the publisher of Science, a top peer-reviewed academic journal. Election as a fellow is a lifetime honor — one of the AAAS’s ...

University of Leeds news

Embargoed until 10:00 GMT, 27 March

Damaging cluster of UK winter storms driven by swirling polar vortex miles above Earth

Powerful winter storms which led to deaths and power outages in the UK and Ireland were made more likely by an intense swirling vortex of winds miles above the Arctic, say scientists.

A team of researchers led by the University of Leeds has pinpointed a new reason for winter storm clusters such as the trio named Dudley, Eunice and Franklin, which hit the nation within the space of a week in February 2022.

The findings which are published today in the journal ...

In the past, intact forests absorbed 7.8 billion tonnes of CO₂ annually – about a fifth of all human emissions – but their carbon storage is increasingly at risk from climate change and human activities such as deforestation. A new study from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) shows that failing to account for the potentially decreasing ability of forests to absorb CO₂ could make reaching the Paris agreement targets significantly harder, if not impossible, and much more costly.

“Delaying action leads to disproportionately higher costs,” explains Michael Windisch, ...

A new medical database automatically compiles the medical records of obese patients and those suffering from obesity-related diseases in a uniquely comprehensive and reliable manner. The initiative, led by Kobe University, offers valuable insights for health promotion and drug development.

“Obesity is at the root of many diseases,” says OGAWA Wataru, an endocrinologist at Kobe University. Obesity has been linked to the development of diabetes, hypertension, gout, coronary heart disease, stroke and many other diseases. Monitoring, treating and preventing obesity and the diseases it can cause is therefore not only good for ...

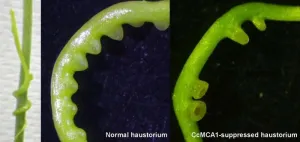

The parasitic vine Cuscuta campestris grows by latching onto the stems and leaves of plants and inserting organs called haustorium into the host plant tissues to draw nutrients. The haustorium is formed when ion channels in the cell membrane are stimulated during coiling and induce a reaction within the cell.

Further, Cuscuta campestris has many types of ion channels, but which ones were linked to the development of haustorium were previously unknown.

“For the first time, the genes involved in sensing ...

A new study led by researchers at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at Institute of Science Tokyo has uncovered a surprising role for calcium in shaping life’s earliest molecular structures. Their findings suggest that calcium ions can selectively influence how primitive polymers form, shedding light on a long-standing mystery: how life’s molecules came to prefer a single “handedness” (chirality).

Like our left and right hands, many molecules exist in two mirror-image forms. Yet life on Earth has a striking preference: ...

People living with Long Covid often feel dismissed, disbelieved and unsupported by their healthcare providers, according to a new study from the University of Surrey.

The study, which was published in the Journal of Health Psychology, looked at how patients with Long Covid experience their illness. The study found that many patients feel they have to prove their illness is physical to be taken seriously and, as a result, often reject psychological support, fearing it implies their symptoms are "all in the mind".

Professor ...

Wearable mobile health technology could help people with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) to stick to exercise regimes that help them to keep the condition under control, a new study reveals.

Researchers studied the behaviour of recently-diagnosed T2D patients in Canada and the UK as they followed a home-based physical activity programme – some of whom wore a smartwatch paired with a health app on their smartphone.

They discovered that MOTIVATE-T2D participants were more likely to start and maintain purposeful exercise at if they had the support of wearable technology- the study successfully recruited 125 participants with an 82% ...

An extinct lineage of parasitic wasps dating from the mid-Cretaceous period and preserved in amber may have used their Venus flytrap-like abdomen to capture and immobilise their prey. Research, published in BMC Biology, finds that the specimens of Sirenobethylus charybdis — named for the sea monster in Greek mythology which swallowed and disgorged water three times a day — date from almost 99 million years ago and may represent a new family of insects.

The morphology of S. charybdis indicates the wasps were ...

A new species of fossil from 444 million years ago that has perfectly preserved insides has been affectionately named ‘Sue’ after its discoverer’s mum.

The result of 25 years of work by a University of Leicester palaeontologist and published in the journal Palaeontology, the study details a new species of multisegmented fossil and is now officially named as Keurbos susanae.

Lead author Professor Sarah Gabbott from the School of Geography, Geology and the Environment said: “‘Sue’ is an inside-out, legless, headless wonder. Remarkably her insides are a mineralised ...