(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR—University of Michigan researchers have developed a statistical method that can be used for such wide-ranging applications as tracing your ancestry, modeling disease spread and studying how animals spread through geographic regions.

One of the method's applications is to give a more complete sense of human ancestry, says Gideon Bradburd, U-M professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. For example, when you send your DNA off for a personalized ancestry report, the report you get back is only a very small view of your family tree pinned in a specific point and space in time.

These types of genetic reports reflect the amount of a person's genome that they've inherited from individuals living in a specific area at a specific point in the past. If your ancestry report says that you're 50% Irish, that means you have a lot of second through fourth cousins who currently live in Ireland, says Bradburd. But in reality, your family tree is much more like a movie than this snapshot.

The statistical method developed by Bradburd and fellow U-M researchers Michael Grundler and Jonathan Terhorst can give people a "movie" version of their ancestry, showing where their ancestors originated and how they moved across the globe. The method uses modern genetic sequence samples, estimates all of the locations of an individual's genetic ancestors, identifies the average location of those individuals based on assumptions about how people move, and tracks it back over centuries.

The researchers' method can be used for more than tracing human ancestry. It can also be used to track the emergence of viruses, the divergence of animal populations and other genealogical tracking. Their results are published in the journal Science.

"There's ways in which consumer ancestry reports are interesting, and certainly it's powerful to learn about your history, especially for folks who've been adopted or orphaned or are disconnected from their family," Bradburd said. "But there are other ways in which these ancestry reports can be really problematic. They really reify notions of the biological essentialism of race because they're presenting these categories of Irish, for example, as if they're ideals, that they're real and unchanging through time."

But researchers know this isn't the case. A field, forged by Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Svante Pääbo, developed the tools to genotype ancient DNA. This allows researchers to trace waves of human populations as they spread throughout the world—particularly in Eurasia, where most of this type of genetic sequencing has been happening, Bradburd says. This has allowed researchers to see how human groups enter and leave geographic regions through time.

"Because the genetic flavor of a location changes so much through time, we know it's meaningless to say, 'This is what it means to be Irish,'" Bradburd said. "It's not just that being 'genetically Irish' doesn't mean anything; it also means that you are everything."

Bradburd points to a thought experiment in human biology: imagine two biological parents and four biological grandparents. This doubles every generation, and it only has to double a relatively small number of generations before there are more people in that direct lineage than there have ever been humans alive on Earth.

This also means that you don't have to go very far back in time to discover that many people share many ancestors.

"Because our pedigrees explode so quickly, they also must collapse in the same sense that you and I must share many, many relatives at many points back in time, and that's true for every person alive on Earth," Bradburd said. "We're all extraordinarily closely related to each other."

The ancestry reports are accurate, Bradburd said, but specifically when they are tied to a time period.

"The ancestry reports aren't wrong, but they're leaving out a very important component, which is the 'when' you have Irish ancestry," Bradburd said. "Because we know the modern human lineage arose in Africa, it is as accurate to say that you have 100% African ancestry at a deeper time horizon."

The statistical method, called Gaia (geographic ancestry inference algorithm), starts by making a very simple assumption about how individuals move: that typically they move locally. The method combines that assumption with the location of modern-day individuals and a genetic structure that relates them called the ancestral recombination graph.

With those two pieces of information and the simple model of how individuals move, the researchers can compute the "most parsimonious locations of ancestors," Bradburd says. The researchers then can propagate that information back through the past.

Bradburd's work is answering a call from the National Academy of Sciences, urging researchers working on human population genetics to move away from race-based labels. While the sociological realities of race are undeniable, racial categories do not make good predictions about genetic variation, he says.

Because of the disconnect between race and genetics, racial labels can often be imprecise: two people might share the same label, but be much more closely or less closely related to each other. In addition, because the genetics in a certain geographic area can shift so much over time, geographic and national labels can also be misleading, Bradburd says.

"Saying you're 'genetically Irish' makes it seem like 'Irish' has always meant the same thing, and genetically we know that is not true and also that anyone who is Irish—meaning they inherited parts of their genome from people who lived in Ireland—is only Irish with respect to a specific time horizon," he said. "That these race labels gloss over both of these important pieces of information is a big loss of specificity and also poses a very real danger to the weaponization of science for political means."

The method Bradburd's team developed can be applied to systems other than human genetics. Researchers can use this method to look at the genetic distribution of the organisms they study. Researchers can also use this method to learn about the migration of organisms—human and otherwise, Bradburd says.

For example, researchers have been able to look at measures of genetic similarity of population between two locations and infer that they are more or less closely connected by migration, or more or less isolated from each other. But this tool allows researchers to pin a timeline on when these movements happened.

And this tool can apply in this case to more than tracing human genetics—it can be used to help determine when a disease might have emerged from a specific region of the world, for example. The U-M group is working with researchers in Australia to learn how mosquitoes colonized islands of the South Pacific, and with researchers in Michigan and Ohio to understand the history and dispersal of the Massasauga rattlesnake.

"It's one of the things I'm quite excited about with this—you can use this method to identify dispersal patterns through time and between specific locations," Bradburd said. "Notions of ancestry don't have to be static. Instead, you should think of them as being dynamic, and interesting and understandable more as a movie than as a picture."

END

A genetic tree as a movie: Moving beyond the still portrait of ancestry

2025-03-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New material gives copper superalloy-like strength

2025-03-27

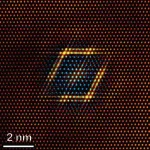

Researchers from the U.S. Army Research Laboratory (ARL) and Lehigh University have developed a groundbreaking nanostructured copper alloy that could redefine high-temperature materials for aerospace, defense and industrial applications.

Their findings, published in the journal Science, introduce a Cu-Ta-Li (Copper-Tantalum-Lithium) alloy with exceptional thermal stability and mechanical strength, making it one of the most resilient copper-based materials ever created.

“This is cutting-edge science, developing a new material ...

Park entrances may be hotspots for infective dog roundworm eggs

2025-03-27

In an analysis of soil samples from twelve parks in Dublin, Ireland, park entrances were more heavily contaminated with infective roundworm eggs than any other tested park location. Jason Keegan of Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Dogs and cats are often infected with parasitic roundworms in the Toxocara genus. Infected animals can release the roundworm eggs into the environment, and humans can become infected after accidental ingestion of the eggs. Many infected humans never experience symptoms, but some may experience mild or severe ...

Commercial fusion power plant closer to reality following research breakthrough

2025-03-27

Successfully harnessing the power of fusion energy could lead to cleaner and safer energy for all – and contribute substantially to combatting the climate crisis. Towards this goal, Type One Energy has published a comprehensive, self-consistent, and robust physics basis for a practical fusion pilot power plant.

This groundbreaking research is presented in a series of six peer-reviewed scientific papers in a special issue of the prestigious Journal of Plasma Physics (JPP), published by Cambridge University Press.

The articles serve as the foundation for the company’s first fusion power plant project, which Type One Energy is developing with the Tennessee ...

The Protein Society announces its 2024 Best Paper recipients

2025-03-27

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact:

John Kuriyan, Editor-in-Chief

Protein Science Journal

Raluca Cadar

The Protein Society

Phone: (844) 377-6834

E-mail: rcadar@proteinsociety.org

LOS ANGELES, CA – The Protein Society, the premier international society dedicated to supporting protein research, announces the winners of the 2024 Protein Science Best Paper Awards, published in its flagship journal, Protein Science. The recipients will be recognized and present their research at the 39th Annual Symposium of The Protein Society, June 26 – 29, 2025, in San Francisco, USA.

The ...

Bing Ren appointed Scientific Director and Chief Executive Officer of the New York Genome Center

2025-03-27

The New York Genome Center (NYGC) is pleased to announce the appointment of Bing Ren, PhD, as its new scientific director and chief executive officer. Dr. Ren will also join Columbia University as a professor in the Departments of Genetics and Development, Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, and Systems Biology and as the associate director of the Roy and Diana Vagelos Institute for Basic Biomedical Science within the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Dr. Ren is renowned for his pioneering research in genomics and epigenetics, with a focus on the regulatory processes that control gene expression. His work has advanced our understanding of how genetic ...

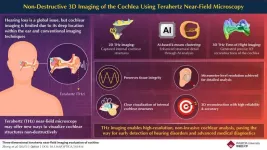

Terahertz imaging: a breakthrough in non-invasive cochlear visualization

2025-03-27

Advancements in healthcare and technology have significantly increased the average human lifespan. However, with longer life comes a higher prevalence of age-related disorders that affect overall well-being. One such condition is hearing loss in older adults, which can severely impact communication, social interactions, and daily functioning.

Hearing relies on the cochlea, a spiral-shaped organ in the inner ear that converts sound waves into neural signals. Any structural or functional impairment of the cochlea ...

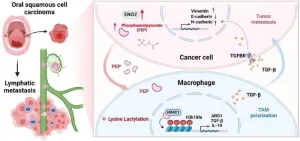

ENO2: a key player in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastasis

2025-03-27

A recent study published in Engineering has shed new light on the mechanisms underlying the metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The research identified enolase 2 (ENO2), a crucial glycolytic enzyme, as a significant factor associated with lymphatic metastasis in HNSCC.

HNSCC is an aggressive cancer with a relatively low 5-year overall survival rate. Cervical lymph node metastasis is a major cause of cancer-related death in HNSCC patients, and effective therapies for metastatic HNSCC are currently lacking. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of HNSCC metastasis ...

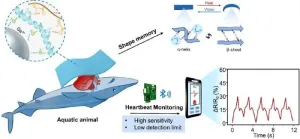

Biocompatible hydrogel enables wearable electronics for monitoring marine life health

2025-03-27

In a recent development published in Engineering, researchers have introduced a novel hybrid keratin (KE) hydrogel integrated with liquid metal (LM), offering new possibilities for monitoring the health of marine inhabitants. This innovation addresses the limitations of traditional wearable electronics in terms of biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and conductivity.

Monitoring the health and migration of marine organisms is crucial for maintaining the balance of marine ecosystems, advancing climate change studies, and safeguarding human health. However, developing sensors for marine organisms is challenging due to the complex ...

We must not ignore eugenics in our genetics curriculum, says professor

2025-03-27

To encourage scientists to speak up when people misuse science to serve political agendas, biology professor Mark Peifer of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill argues that eugenics should be included in college genetics curriculums. In an opinion paper publishing March 27 in the Cell Press journal Trends in Genetics, Peifer explains how he incorporated a discussion of eugenics into his molecular genetics course last year and why understanding the history of the field is critical for up-and-coming scientists.

“Eugenics is not dead but continues to influence science and policy today,” writes Peifer ...

Semaglutide and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Risk Among Patients With Diabetes

2025-03-27

About The Study: The results of this cohort study suggest that semaglutide use was associated with an increased risk of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in patients with diabetes. However, the study’s retrospective design presents limitations, as it can only infer associations rather than establish causality; further studies are needed.

Corresponding Authors: To contact the corresponding authors, email Chun-Ju Lin, MD (doctoraga@gmail.com) and James Cheng-Chung ...