New York, NY [April 14, 2025]—A new multicenter study by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute-funded Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) and colleagues around the world, has discovered that the genes we are born with—known as germline genetic variants—play a powerful, underappreciated role in how cancer develops and behaves.

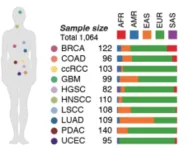

Published in the April 14 online issue of Cell [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.03.026], the study is the first to detail how millions of inherited genetic differences influence the activity of thousands of proteins within tumors. Drawing on data from more than 1,000 patients across 10 different cancer types, the research illustrates how a person’s unique genetic makeup can shape the biology of their cancer.

The findings could have major implications for how doctors treat cancer in the future. While current treatments are largely guided by the genetic makeup of a patient’s tumor, this research suggests that looking at a patient’s inherited DNA could further refine diagnosis, risk prediction, and therapy selection.

“Every person carries a unique combination of genetic variants from birth, and these inherited differences quietly shape how our cells function throughout life,” says co-corresponding study author Zeynep H. Gümüş, PhD, Associate Professor of Genetics and Genomic Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “What we’ve shown is that these variants don’t just sit in the background—they can play an active role in how tumors form, how they evolve, and even how they respond to treatment. This opens new possibilities for tailoring cancer care based not only on the tumor itself, but also on the patient’s underlying genetic makeup.”

Until now, most cancer research has focused on somatic mutations—changes that occur in cells over a person’s lifetime. But inherited germline variants outnumber somatic mutations by a wide margin, and their impact on cancer has remained poorly understood, say the investigators.

To conduct the study, the researchers used an advanced technique known as precision peptidomics, which enabled them to examine how specific inherited mutations modulate the structure, stability, and function of proteins in cancer cells. By mapping more than 330,000 protein-coding germline variants, the team uncovered how these inherited differences can alter protein activity, impact gene expression, and even drive how tumors interact with the immune system.

“Our study flips the script by showing that inherited DNA changes can influence how genes are expressed and how proteins—key drivers of cancer behavior—are produced and modified in tumors. In doing so, these variants help explain some of the wide variation doctors see in how cancer appears, progresses, and responds to therapies from one patient to another,” says Dr. Gümüş.

The research adds to growing evidence that personalized cancer care should take into account not just the tumor’s mutations, but the genetic background of the person, too. However, the investigators caution that the study’s findings are based on data from a primarily European-ancestry cohort, and further research is needed to ensure these insights apply across multi-ancestry populations.

“This is a major step toward precision medicine that considers the whole individual—not just the cancer,” says Myvizhi Esai Selvan, PhD, co-first author of the study, who is an Instructor of Genetics and Genomics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “In the evolution of cancer, the inherited genome sets the stage. It helps determine which mutations matter, how aggressive a tumor might become, and how the body’s immune system will respond.”

The team is now working on applying these insights in two major areas:

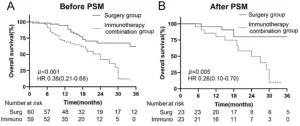

Cancer immunotherapy: In partnership with the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Immune Monitoring and Analysis Centers, researchers are investigating why some patients respond well to immunotherapy while others do not, an area where inherited genetic differences could hold the key.

Lung cancer risk prediction: Through the Mount Sinai Million Health Discoveries Program and the Million Veteran Program, the researchers are developing computational models to predict lung cancer risk based on a person’s inherited genetic profile. These tools could help determine who would benefit most from early screening, improving outcomes through early detection.

The study is titled “Precision Proteogenomics Reveals Pan-Cancer Impact of Germline Variants.”

For the full list of authors, as well as details on funding, please refer to the Cell paper: [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.03.026].

About the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is internationally renowned for its outstanding research, educational, and clinical care programs. It is the sole academic partner for the seven member hospitals* of the Mount Sinai Health System, one of the largest academic health systems in the United States, providing care to New York City’s large and diverse patient population.

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai offers highly competitive MD, PhD, MD-PhD, and master’s degree programs, with enrollment of more than 1,200 students. It has the largest graduate medical education program in the country, with more than 2,600 clinical residents and fellows training throughout the Health System. Its Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences offers 13 degree-granting programs, conducts innovative basic and translational research, and trains more than 560 postdoctoral research fellows.

Ranked 11th nationwide in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is among the 99th percentile in research dollars per investigator according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. More than 4,500 scientists, educators, and clinicians work within and across dozens of academic departments and multidisciplinary institutes with an emphasis on translational research and therapeutics. Through Mount Sinai Innovation Partners (MSIP), the Health System facilitates the real-world application and commercialization of medical breakthroughs made at Mount Sinai.

-------------------------------------------------------

* Mount Sinai Health System member hospitals: The Mount Sinai Hospital; Mount Sinai Brooklyn; Mount Sinai Morningside; Mount Sinai Queens; Mount Sinai South Nassau; Mount Sinai West; and New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai

END