(Press-News.org) Images available via link in the notes section

University of Oxford researchers have helped overturn the popular theory that water on Earth originated from asteroids bombarding its surface;

Scientists have analysed a meteorite analogous to the early Earth to understand the origin of hydrogen on our planet.

The research team demonstrated that the material which built our planet was far richer in hydrogen than previously thought.

The findings, which support the theory that the formation of habitable conditions on Earth did not rely on asteroids hitting the Earth, have been published today (Wednesday 16 April) in the journal Icarus.

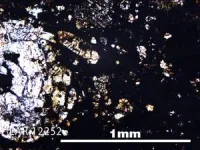

A team of researchers at the University of Oxford have uncovered crucial evidence for the origin of water on Earth. Using a rare type of meteorite, known as an enstatite chondrite, which has a composition analogous to that of the early Earth (4.55 billion years ago), they have found a source of hydrogen which would have been critical for the formation of water molecules.

Crucially, they demonstrated that the hydrogen present in this material was intrinsic, and not from contamination. This suggests that the material which our planet was built from was far richer in hydrogen than previously thought.

Without hydrogen, a fundamental elemental building-block of water, it would have been impossible for our planet to develop the conditions to support life. The origin of hydrogen, and by extension water, on Earth has been highly debated, with many believing that the necessary hydrogen was delivered by asteroids from outer space during Earth’s first approximately 100 million years. But these new findings contradict this, suggesting instead that Earth had the hydrogen it needed to create water from when it first formed.

The research team analysed the elemental composition of a meteorite known as LAR 12252, originally collected from Antarctica. They used an elemental analysis technique called X-Ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) spectroscopy* at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron at Harwell, Oxfordshire.

A previous study led by a French team had originally identified traces of hydrogen within the meteorite inside organic materials and non-crystalline parts of the chondrules (millimetre-sized spherical objects within the meteorite). However, the remainder was unaccounted for – meaning it was unclear whether the hydrogen was native or due to terrestrial contamination.

The Oxford team suspected that significant amounts of the hydrogen may be attached to the meteorite’s abundant sulphur. Using the synchrotron, they shone a powerful beam of X-rays onto the meteorite’s structure to search for sulphur-bearing compounds.

When initially scanning the sample, the team focussed their efforts on the non-crystalline parts of the chondrules, where hydrogen had been found before. But when serendipitously analysing the material just outside of one of these chondrules, composed of a matrix of extremely fine (sub-micrometre) material, the team discovered that the matrix itself was incredibly rich in hydrogen sulphide. In fact, their analysis found that the amount of hydrogen in the matrix was five times higher than that of the non-crystalline sections.

In contrast, in other parts of the meteorite that had cracks and signs of obvious terrestrial contamination (such as rust), very little or no hydrogen was present. This makes it highly unlikely that the hydrogen sulphide compounds detected by the team originated from an Earthly source.

Since the proto-Earth was made of material similar to enstatite chondrites, this suggests that by the time the forming planet had become large enough to be struck by asteroids, it would have amassed enough reserves of hydrogen to explain Earth’s present-day water abundance.

Tom Barrett, DPhil student in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford, who led the study, said: “We were incredibly excited when the analysis told us the sample contained hydrogen sulphide – just not where we expected! Because the likelihood of this hydrogen sulphide originating from terrestrial contamination is very low, this research provides vital evidence to support the theory that water on Earth is native - that it is a natural outcome of what our planet is made of.”

Co-author Associate Professor James Bryson (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford) added: “A fundamental question for planetary scientists is how Earth came to look like it does today. We now think that the material that built our planet – which we can study using these rare meteorites – was far richer in hydrogen than we thought previously. This finding supports the idea that the formation of water on Earth was a natural process, rather than a fluke of hydrated asteroids bombarding our planet after it formed.”

* X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) spectroscopy is a technique that is used to identify what elements are in a material and what their chemical state is. It works by shining X-rays onto a sample, causing the atoms to absorb energy in a way that depends on what the element is, the chemical form it is in (e.g., an oxide, a sulphide, etc), and how the atoms are bonded with others.

Notes:

For media enquiries and interview requests, contact Associate Professor James Bryson james.bryson@earth.ox.ac.uk and Tom Barrett thomas.barrett@st-annes.ox.ac.uk

Images relating to the study which can be used in articles can be found at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1S6sNLYfXJo9fuB8e_jCGSkU46VLaXqwR?usp=sharing These images are for editorial purposes relating to this press release ONLY and MUST be credited (see file name). They MUST NOT be sold on to third parties.

The study ‘The source of hydrogen in earth's building blocks’ will be published in ‘Icarus’ at 04:01 BST Wednesday 16 April / 23:01 ET Tuesday 15 April 2025 at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2025.116588

To view a copy of the study before this under embargo, contact Associate Professor James Bryson james.bryson@earth.ox.ac.uk and Tom Barrett thomas.barrett@st-annes.ox.ac.uk

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the ninth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

END

Scientists find evidence that overturns theories of the origin of water on Earth

2025-04-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Foraging on the wing: How can ecologically similar birds live together?

2025-04-16

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A spat between birds at your backyard birdfeeder highlights the sometimes fierce competition for resources that animals face in the natural world, but some ecologically similar species appear to coexist peacefully. A classic study in songbirds by Robert MacArthur, one of the founders of modern ecology, suggested that similar wood warblers — insect-eating, colorful forest songbirds — can live in the same trees because they actually occupy slightly different locations in the tree and presumably eat different insects. Now, a new study is using modern techniques to revisit MacArthur’s ...

Little birds’ personalities shine through their song – and may help find a mate

2025-04-16

In birds, singing behaviours play a critical role in mating and territory defence.

Although birdsong can signal individual quality and personality, very few studies have explored the relationship between individual personality and song complexity, and none has investigated this in females, say Flinders University animal behaviour experts.

They have examined the relationships between song complexity and two personality traits (exploration and aggressiveness) in wild superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) in Australia, a species in which both sexes learn to produce complex songs.

“Regardless of their sex ...

Primate mothers display different bereavement response to humans

2025-04-16

Macaque mothers experience a short period of physical restlessness after the death of an infant, but do not show typical human signs of grief, such as lethargy and appetite loss, finds a new study by UCL anthropologists.

Published in Biology Letters, the researchers found that bereaved macaque mothers spent less time resting (sleep, restful posture, relaxing) than the non-bereaved females in the first two weeks after their infants’ deaths.

Researchers believe this physical restlessness could represent an initial period of ‘protest’ among the bereaved macaque mothers, similar ...

New pollen-replacing food for honey bees brings new hope for survival

2025-04-16

PULLMAN, Wash., -- Scientists have unveiled a new food source designed to sustain honey bee colonies indefinitely without natural pollen.

Published April 16 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the research from Washington State University and APIX Biosciences NV in Wingene, Belgium details successful trials where nutritionally stressed colonies, deployed for commercial crop pollination in Washington state, thrived on the new food source.

This innovation, which resembles the man-made diets ...

Gene-based blood test for melanoma may catch early signs of cancer’s return

2025-04-15

Monitoring blood levels of DNA fragments shed by dying tumor cells may accurately predict skin cancer recurrence, a new study shows.

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health and its Perlmutter Cancer Center, the study showed that approximately 80% of stage III melanoma patients who had detectable levels of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) before they started treatment to suppress their tumors went on to experience recurrence.

The researchers also found that the disease returned more than four times faster in this group than in those with no detectable levels of the biomarker, and the higher ...

Common genetic variants linked to drug-resistant epilepsy

2025-04-15

Certain common genetic changes might make some people with focal epilepsy less responsive to seizure medications, finds a new global study led by researchers at UCL and UTHealth Houston.

Focal epilepsy is a condition where seizures start in one part of the brain. It is the most common type of epilepsy.

Antiseizure medication is usually prescribed for people with the condition. However, for one in three people with epilepsy (around 20 million individuals worldwide), current antiseizure medications are ineffective. This means ...

Brisk walking pace + time spent at this speed may lower risk of heart rhythm abnormalities

2025-04-15

A brisk walking pace, and the amount of time spent at this speed, may lower the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities, such as atrial fibrillation, tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), and bradycardia (very slow heartbeat), finds research published online in the journal Heart.

The findings were independent of known cardiovascular risk factors, but strongest in women, the under 60s, those who weren’t obese, and those with pre-existing long term conditions.

Heart rhythm abnormalities (arrhythmias) are common, note the authors, with atrial fibrillation ...

Single mid-afternoon preventer inhaler dose may be best timing for asthma control

2025-04-15

A single daily preventer dose of inhaled corticosteroid (beclomethasone), taken mid afternoon, may be the best timing for effective asthma control as it suppresses the usual nocturnal worsening of symptoms more effectively than dosing regimens at other times of the day, suggest the results of a small clinical trial published in the journal Thorax.

If the findings are confirmed in larger studies, this approach may lead to better clinical outcomes for patients without increasing unwanted steroidal ...

Symptoms of ice cold feet + heaviness in legs strongly linked to varicose veins

2025-04-15

Hypersensitivity to the cold, especially ice cold feet, as well as a feeling of heaviness in the legs, are linked to the presence of varicose veins, finds a large study published in the open access journal Open Heart.

Cold hypersensitivity is often underestimated as a subjective symptom, say the researchers.

Varicose veins are usually caused by impaired functioning of the deep or superficial veins, and the perforator veins (short veins that link the superficial and deep venous systems in the legs).

The prevalence of varicose veins ranges from 2% to 30% in adults, with women at higher risk. And symptoms include sensations ...

Brain areas necessary for reasoning identified

2025-04-15

A team of researchers at UCL and UCLH have identified the key brain regions that are essential for logical thinking and problem solving.

The findings, published in Brain, help to increase our understanding of how the human brain supports our ability to comprehend, draw conclusions, and deal with new and novel problems – otherwise known as reasoning skills.

To determine which brain areas are necessary for a certain ability, researchers study patients with brain lesions (an area of damage in the brain) caused by stroke or brain tumours. This approach, known ...