(Press-News.org) Kyoto, Japan -- There's a sensation that you experience -- near a plane taking off or a speaker bank at a concert -- from a sound so total that you feel it in your very being. When this happens, not only do your brain and ears perceive it, but your cells may also.

Technically speaking, sound is a simple phenomenon, consisting of compressional mechanical waves transmitted through substances, which exists universally in the non-equilibrated material world. Sound is also a vital source of environmental information for living beings, while its capacity to induce physiological responses at the cell level is only just beginning to be understood.

Following on previous work from 2018, a team of researchers at Kyoto University have been inspired by research in mechanobiology and body-conducted sound -- the sound environment in body tissues -- indicating that acoustic pressure transmitted by sound may be sufficient to induce cellular responses.

"To investigate the effect of sound on cellular activities, we designed a system to bathe cultured cells in acoustic waves," says corresponding author Masahiro Kumeta.

The team first attached a vibration transducer upside-down on a shelf. Then using a digital audio player connected to an amplifier, they sent sound signals through the transducer to a diaphragm attached to a cell culture dish. This allowed the researchers to emit acoustic pressure within the range of physiological sound to cultured cells.

Following this experiment, the researchers analyzed the effect of sound on cells using RNA-sequencing, microscopy, and other methods. Their results revealed cell-level responses to the audible range of acoustic stimulation.

In particular, the team noticed the significant effect of sound in suppressing adipocyte differentiation, the process by which preadipocytes transform into fat cells, unveiling the possibility of utilizing acoustics to control cell and tissue states.

"Since sound is non-material, acoustic stimulation is a tool that is non-invasive, safe, and immediate, and will likely benefit medicine and healthcare," says Kumeta.

The research team also identified about 190 sound-sensitive genes, noted the effect of sound in controlling cell adhesion activity, and observed the subcellular mechanism through which sound signals are transmitted.

In addition to providing compelling evidence of the perception of sound at the cell level, this study also challenges the traditional concept of sound perception by living beings, which is that it is mediated by receptive organs like the brain. It turns out that your cells respond to sounds, too.

###

The paper "Acoustic modulation of mechanosensitive genes and adipocyte differentiation" appeared on 16 April 2025 in Communications Biology, with doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-07969-1

About Kyoto University

Kyoto University is one of Japan and Asia's premier research institutions, founded in 1897 and responsible for producing numerous Nobel laureates and winners of other prestigious international prizes. A broad curriculum across the arts and sciences at undergraduate and graduate levels complements several research centers, facilities, and offices around Japan and the world. For more information, please see: http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en

END

Your cells can hear

Uncovering the relationship between life and sound

2025-04-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Farm robot autonomously navigates, harvests among raised beds

2025-04-16

Strawberry fields forever will exist for the in-demand fruit, but the laborers who do the backbreaking work of harvesting them might continue to dwindle. While raised, high-bed cultivation somewhat eases the manual labor, the need for robots to help harvest strawberries, tomatoes, and other such produce is apparent.

As a first step, Osaka Metropolitan University Assistant Professor Takuya Fujinaga has developed an algorithm for robots to autonomously drive in two modes: moving to a pre-designated destination and moving alongside ...

The bear in the (court)room: who decides on removing grizzly bears from the endangered species list?

2025-04-16

By Dr Kelly Dunning

The Endangered Species Act (ESA), now 50 years old, was once a rare beacon of bipartisan unity, signed into law by President Richard Nixon with near-unanimous political support. Its purpose was clear: protect imperiled species and enable their recovery using the best available science to do so. Yet, as our case study on the grizzly bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem reveals, wildlife management under the ESA has changed, becoming a political battleground where science is increasingly drowned out by partisan ideology, bureaucratic delays, power struggles, and competing political interests. ...

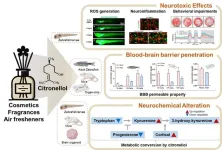

First study reveals neurotoxic potential of rose-scented citronellol at high exposure levels

2025-04-16

Citronellol, a rose-scented compound commonly found in cosmetics and household products, has long been considered safe. However, a Korean research team has, for the first time, identified its potential to cause neurotoxicity when excessively exposed.

A collaborative research team led by Dr. Myung Ae Bae at the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT) and Professors Hae-Chul Park and Suhyun Kim at Korea University has discovered that high concentrations of citronellol can trigger neurological and behavioral toxicity. The study, published in the Journal ...

For a while, crocodile

2025-04-16

Most people think of crocodylians as living fossils— stubbornly unchanged, prehistoric relics that have ruled the world’s swampiest corners for millions of years. But their evolutionary history tells a different story, according to new research led by the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) and the University of Utah.

Crocodylians are surviving members of a 230-million-year lineage called crocodylomorphs, a group that includes living crocodylians (i.e. crocodiles, alligators and gharials) and their many extinct ...

Scientists find evidence that overturns theories of the origin of water on Earth

2025-04-16

Images available via link in the notes section

University of Oxford researchers have helped overturn the popular theory that water on Earth originated from asteroids bombarding its surface;

Scientists have analysed a meteorite analogous to the early Earth to understand the origin of hydrogen on our planet.

The research team demonstrated that the material which built our planet was far richer in hydrogen than previously thought.

The findings, which support the theory that the formation of habitable conditions on Earth did not rely on asteroids ...

Foraging on the wing: How can ecologically similar birds live together?

2025-04-16

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A spat between birds at your backyard birdfeeder highlights the sometimes fierce competition for resources that animals face in the natural world, but some ecologically similar species appear to coexist peacefully. A classic study in songbirds by Robert MacArthur, one of the founders of modern ecology, suggested that similar wood warblers — insect-eating, colorful forest songbirds — can live in the same trees because they actually occupy slightly different locations in the tree and presumably eat different insects. Now, a new study is using modern techniques to revisit MacArthur’s ...

Little birds’ personalities shine through their song – and may help find a mate

2025-04-16

In birds, singing behaviours play a critical role in mating and territory defence.

Although birdsong can signal individual quality and personality, very few studies have explored the relationship between individual personality and song complexity, and none has investigated this in females, say Flinders University animal behaviour experts.

They have examined the relationships between song complexity and two personality traits (exploration and aggressiveness) in wild superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) in Australia, a species in which both sexes learn to produce complex songs.

“Regardless of their sex ...

Primate mothers display different bereavement response to humans

2025-04-16

Macaque mothers experience a short period of physical restlessness after the death of an infant, but do not show typical human signs of grief, such as lethargy and appetite loss, finds a new study by UCL anthropologists.

Published in Biology Letters, the researchers found that bereaved macaque mothers spent less time resting (sleep, restful posture, relaxing) than the non-bereaved females in the first two weeks after their infants’ deaths.

Researchers believe this physical restlessness could represent an initial period of ‘protest’ among the bereaved macaque mothers, similar ...

New pollen-replacing food for honey bees brings new hope for survival

2025-04-16

PULLMAN, Wash., -- Scientists have unveiled a new food source designed to sustain honey bee colonies indefinitely without natural pollen.

Published April 16 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the research from Washington State University and APIX Biosciences NV in Wingene, Belgium details successful trials where nutritionally stressed colonies, deployed for commercial crop pollination in Washington state, thrived on the new food source.

This innovation, which resembles the man-made diets ...

Gene-based blood test for melanoma may catch early signs of cancer’s return

2025-04-15

Monitoring blood levels of DNA fragments shed by dying tumor cells may accurately predict skin cancer recurrence, a new study shows.

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health and its Perlmutter Cancer Center, the study showed that approximately 80% of stage III melanoma patients who had detectable levels of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) before they started treatment to suppress their tumors went on to experience recurrence.

The researchers also found that the disease returned more than four times faster in this group than in those with no detectable levels of the biomarker, and the higher ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Your cells can hearUncovering the relationship between life and sound