New research from Barcelona and Dresden: Glycolysis — the process of converting sugar into energy — plays a key role in early development.

More than fuel: Glycolysis doesn’t just power cells — it helps steer them toward specific tissue types at critical moments in development.

Better embryo models: Stem-cell–based embryo models that rely on glycolysis form structures more similar to natural embryos.

Predict and control development in a dish: These findings improve our ability to predict and control how stem-cell-based embryo models will develop, unlocking further potential for biological discovery, disease modelling, and drug toxicity testing.

Glycolysis is an ancient metabolic activity. It consists of a set of reactions that convert glucose into energy. This central process allows cells to grow, divide, and stay alive. It has accompanied life since its origin, from single cells to complex organisms like mammals. Scientists have extensively studied the role of metabolism in individual cells to understand how it influences their energetic state, but little has been studied about the effect of glycolysis on the decisions that cells or groups of cells make.

Now, researchers at EMBL Barcelona, Spain, and at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, uncover the instructive potential of glycolysis. They show that rather than exclusively providing energy to the cell, glycolysis is able to control, at different stages of early embryonic development, cell fate decisions and the end-state appearance of stem cell-based embryo models.

In two back-to-back publications in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers from the groups of Vikas Trivedi at EMBL Barcelona and Jesse Veenvliet at the MPI-CBG have used gastruloids and trunk-like structures, in vitro stem cell-based embryo models composed of mouse embryonic stem cells, to study the early steps in the formation of the body plan—a process that lays the foundation for future organ development. Kristina Stapornwongkul, postdoc in the Trivedi group and incoming group leader at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) in Vienna, Austria, from September 2025, studied the role of glycolysis by changing the glucose concentration in the media where cells live and feed. Alba Villaronga-Luque and Ryan Savill, both doctoral students in the Veenvliet group, studied why some trunk-like structures look more like the natural embryo than others by using machine learning to integrate imaging data with profiles of active genes and metabolites over time and found a critical role for glycolysis.

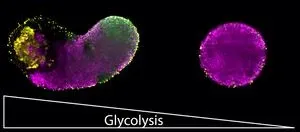

Stapornwongkul realised that blocking glycolysis disrupted the formation of two important tissue types: mesoderm – which later develops into muscles, bones, or blood – and endoderm – which gives rise to organs like the liver or the lungs. Instead, more cells decided to turn into ectoderm tissue, the type that eventually give rises to our nervous system. This study shows that glycolysis helps activate key signalling pathways (Wnt, Nodal, and Fgf) that guide cells towards mesoderm and endoderm fates. When glycolysis was blocked, the signals weakened and cells developed into ectoderm cells. However, when these signals were artificially boosted, normal cell fate decisions were restored, even without glycolysis taking place. This highlights the crucial role of metabolism as an upstream regulator/activator of specific signalling pathways that influence cellular decisions. Being able to control cell fate through altering media composition means that one could also direct cell differentiation towards the tissue type one is interested in.

“What was most surprising to me was this clear dual role of glycolysis: its bioenergetic function important for growth and its signalling function crucial for cell fate decisions. When we inhibited glycolysis, we clearly saw the loss of the endoderm and mesoderm, but we were able to rescue these cell types by activating the signalling pathways, even in the absence of glycolysis, meaning without restoring growth. This shows that we can decouple glycolysis’s bioenergetic role from its role as an upstream signalling regulator, underlining the existence of two distinct functions during early development,” Stapornwongkul said.

“The exciting thing about Kristina’s work is the hierarchical relationship between metabolism and signalling, at least in the earliest stages of organismal development. This result contributes to an emerging perspective on the relationship between metabolism and patterning, a subject of interest to other labs within EMBL and beyond. From an evolutionary perspective, this is exciting because metabolism predates signalling: even single-cell organisms rely on metabolism, while signalling emerged later in evolution. This has sparked my curiosity about the role of metabolism in the origin of multicellularity. This study marks the beginning of an exciting new direction for my group,” Trivedi said.

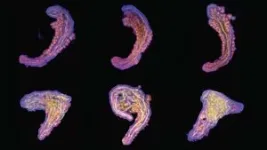

Villaronga-Luque and Savill found that early changes in metabolism cause differences in the end-state appearance of trunk-like structures, a stem-cell-based model of embryonic trunk development that forms the tissues giving rise to the spine (mesoderm) and the spinal cord (ectoderm). These structures make it possible to study mammalian embryo development, which is otherwise hidden in the uterus of the mothers, in large numbers of samples without the need for animal experiments. Although many characteristics of these stem cell-based embryo models are similar to those of an embryo, they are unable to develop into fully functional organisms.

A major hurdle for their widespread use is that they are much more variable than the embryo: even when grown under identical conditions, some stem cell clumps develop into structures very similar to the embryo, whereas others don’t. Such variability makes it harder to use them for research purposes that require a highly reproducible baseline, such as disease modelling or toxicity studies. Villaronga-Luque and Savill observed that specifically, the balance between two different processes that produce energy—glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation—affects the variability of the stem cell-based embryo models. With glycolysis, cells make energy by breaking down glucose. The trunk-like structures with a sort of ‘sweet tooth,’ depending more on glycolysis to obtain their energy by breaking down sugar, develop the most similarly to an embryo, whereas the ones that lacked the ‘sweet tooth’ mostly formed ectoderm. Like Stapornwongkul, they found that glycolysis activates signalling pathways like Wnt that influence cellular decisions and, eventually, how much the structures resemble the embryo. Finally, they showed that boosting glycolysis with drugs improved the appearance of the trunk-like structures.

“To uncover the reason for this variability in stem cell-based embryo models, you need to have measures early in the development to see what goes wrong. However, such measurements typically destroy the sample, such that we don’t know if it will develop into a successful structure or not. This is the challenge we were able to tackle.” Villaronga-Luque said.

“By combining quantitative imaging analysis with machine learning, we found key characteristics of the structures that can predict how their development will turn out. With this predictive power in hand, we could then investigate the expression profiles of structures for which the end state would otherwise be unknown,” said Savill.

“By being able to predict the future appearance of a stem cell-based embryo model, our team could show that the early metabolic state controls how much the model looks like the embryo, which can be regulated by altering the metabolic activity with drugs. Such predictive power for stem cell-based embryo models and also other types of organoids has the potential not only to help to make new fundamental biological discoveries but also to improve stem cell-based embryo models for applications that require high reproducibility, including disease modelling, genetic screens, and toxicity studies.” Veenvliet said.

These studies mark the beginning of a new paradigm for developmental and tissue biology. It brings metabolism to the spotlight for studying the early stages of development, giving the research community a new tool to study early cell decisions and embryo development. Excitingly, the two studies show that at different stages of embryogenesis, glycolysis acts through a similar mechanism to ensure proper development of the body plan.

Original Publications:

Alba Villaronga-Luque, Ryan G Savill, Natalia López-Anguita, Adriano Bolondi, Sumit Garai, Seher Ipek Gassaloglu, Roua Rouatbi, Kathrin Schmeisser, Aayush Poddar, Lisa Bauer, Tiago Alves, Sofia Traikov, Jonathan Rodenfels, Triantafyllos Chavakis, Aydan Bulut-Karslioglu, Jesse V Veenvliet: Integrated molecular-phenotypic profiling reveals metabolic control of morphological variation in a stem-cell-based embryo model. Cell Stem Cell, 16 April, 2025,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.03.012

Kristina S. Stapornwongkul, Elisa Hahn, Patryk Polinski, Laura Salamó Palau, Krisztina Arato, LiAng Yao, Kate Williamson, Nicola Gritti, Kerim Anlas, Mireia Osuna Lopez, Kiran R. Patil, Idse Heemskerk, Miki Ebisuya, and Vikas Trivedi: Glycolytic activity instructs germ layer proportions through regulation of Nodal and Wnt signaling, Cell Stem Cell (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.03.011

END