(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Cleft lip and cleft palate are among the most common birth defects, occurring in about one in 1,050 births in the United States. These defects, which appear when the tissues that form the lip or the roof of the mouth do not join completely, are believed to be caused by a mix of genetic and environmental factors.

In a new study, MIT biologists have discovered how a genetic variant often found in people with these facial malformations leads to the development of cleft lip and cleft palate.

Their findings suggest that the variant diminishes cells’ supply of transfer RNA, a molecule that is critical for assembling proteins. When this happens, embryonic face cells are unable to fuse to form the lip and roof of the mouth.

“Until now, no one had made the connection that we made. This particular gene was known to be part of the complex involved in the splicing of transfer RNA, but it wasn’t clear that it played such a crucial role for this process and for facial development. Without the gene, known as DDX1, certain transfer RNA can no longer bring amino acids to the ribosome to make new proteins. If the cells can’t process these tRNAs properly, then the ribosomes can’t make protein anymore,” says Michaela Bartusel, an MIT research scientist and the lead author of the study.

Eliezer Calo, an associate professor of biology at MIT, is the senior author of the paper, which appears today in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Genetic variants

Cleft lip and cleft palate, also known as orofacial clefts, can be caused by genetic mutations, but in many cases, there is no known genetic cause.

“The mechanism for the development of these orofacial clefts is unclear, mostly because they are known to be impacted by both genetic and environmental factors,” Calo says. “Trying to pinpoint what might be affected has been very challenging in this context.”

To discover genetic factors that influence a particular disease, scientists often perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which can reveal variants that are found more often in people who have a particular disease than in people who don’t.

For orofacial clefts, some of the genetic variants that have regularly turned up in GWAS appeared to be in a region of DNA that doesn’t code for proteins. In this study, the MIT team set out to figure out how variants in this region might influence the development of facial malformations.

Their studies revealed that these variants are located in an enhancer region called e2p24.2. Enhancers are segments of DNA that interact with protein-coding genes, helping to activate them by binding to transcription factors that turn on gene expression.

The researchers found that this region is in close proximity to three genes, suggesting that it may control the expression of those genes. One of those genes had already been ruled out as contributing to facial malformations, and another had already been shown to have a connection. In this study, the researchers focused on the third gene, which is known as DDX1.

DDX1, it turned out, is necessary for splicing transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, which play a critical role in protein synthesis. Each transfer RNA molecule transports a specific amino acid to the ribosome — a cell structure that strings amino acids together to form proteins, based on the instructions carried by messenger RNA.

While there are about 400 different tRNAs found in the human genome, only a fraction of those tRNAs require splicing, and those are the tRNAs most affected by the loss of DDX1. These tRNAs transport four different amino acids, and the researchers hypothesize that these four amino acids may be particularly abundant in proteins that embryonic cells that form the face need to develop properly.

When the ribosomes need one of those four amino acids, but none of them are available, the ribosome can stall, and the protein doesn’t get made.

The researchers are now exploring which proteins might be most affected by the loss of those amino acids. They also plan to investigate what happens inside cells when the ribosomes stall, in hopes of identifying a stress signal that could potentially be blocked and help cells survive.

Malfunctioning tRNA

While this is the first study to link tRNA to craniofacial malformations, previous studies have shown that mutations that impair ribosome formation can also lead to similar defects. Studies have also shown that disruptions of tRNA synthesis — caused by mutations in the enzymes that attach amino acids to tRNA, or in proteins involved in an earlier step in tRNA splicing — can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders.

“Defects in other components of the tRNA pathway have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental disease,” Calo says. “One interesting parallel between these two is that the cells that form the face are coming from the same place as the cells that form the neurons, so it seems that these particular cells are very susceptible to tRNA defects.”

The researchers now hope to explore whether environmental factors linked to orofacial birth defects also influence tRNA function. Some of their preliminary work has found that oxidative stress — a buildup of harmful free radicals — can lead to fragmentation of tRNA molecules. Oxidative stress can occur in embryonic cells upon exposure to ethanol, as in fetal alcohol syndrome, or if the mother develops gestational diabetes.

“I think it is worth looking for mutations that might be causing this on the genetic side of things, but then also in the future, we would expand this into which environmental factors have the same effects on tRNA function, and then see which precautions might be able to prevent any effects on tRNAs,” Bartusel says.

###

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Pew Charitable Trusts.

END

New study reveals how cleft lip and cleft palate can arise

MIT biologists have found that defects in some transfer RNA molecules can lead to the formation of these common conditions

2025-04-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists hack cell entry to supercharge cancer drugs

2025-04-17

A new discovery could pave the way for more effective cancer treatment by helping certain drugs work better inside the body.

Scientists at Duke University School of Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and University of Arkansas have found a way to improve the uptake of a promising class of cancer-fighting drugs called PROTACs, which have struggled to enter cells due to their large size.

The new method works by taking advantage of a protein called CD36 that helps pull substances into cells. By designing drugs to use this CD36 pathway, researchers delivered 7.7 to 22.3 times more of the drug inside cancer cells, making ...

Study: Experimental bird flu vaccine excels in animal models

2025-04-17

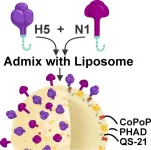

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A vaccine under development at the University at Buffalo has demonstrated complete protection in mice against a deadly variant of the virus that causes bird flu.

The work, detailed in a study published today (April 17) in the journal Cell Biomaterials, focuses on the H5N1 variant known as 2.3.4.4b, which has caused widespread outbreaks in wild birds and poultry, in addition to infecting dairy cattle, domesticated cats, sea lions and other mammals.

In the study, scientists describe a process they’ve developed for creating doses with precise ...

Real-world study finds hydroxyurea effective long-term in children living with sickle cell disease

2025-04-17

(WASHINGTON, April 17, 2024) — Hydroxyurea remains effective long-term in reducing emergency department visits and hospital days for children living with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to new research published in Blood Advances.

“This is one of the first large, real-world, long-term studies to assess the efficacy of hydroxyurea outside of a controlled setting,” said study author Paul George, MD, a pediatric hematology/oncology fellow and PhD candidate at Emory University School of Medicine and Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Children’s ...

FAU designated a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Research

2025-04-17

Florida Atlantic University has been recognized as a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Research (CAE-R) by the National Security Agency (NSA) and its partners in the National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity (NCAE-C). This prestigious designation, awarded through the academic year 2030, affirms the university’s leadership and innovation in the field of cybersecurity research at the doctoral level.

This recognition places FAU among an elite group of institutions nationwide that have demonstrated a sustained commitment to cutting-edge research in cyber defense and security. The CAE-R designation is awarded to universities whose programs meet rigorous ...

European potato genome decoded: Small gene pool with large differences

2025-04-17

A research team has decoded the genome of historic potato cultivars and used this resource to develop an efficient method for analysis of hundreds of additional potato genomes.

Potatoes are a staple food for over 1.3 billion people. But despite their importance for global food security, breeding successes have been modest. Some of the most popular potato cultivars were bred many decades ago. The reason for this limited success is the complex genome of the potato: there are four copies of the genome in each cell instead of just two. ...

Nontraditional risk factors shed light on unexplained strokes in adults younger than 50

2025-04-17

Research Highlights:

Among adults ages 18-49 (median age of 41 years) who were born with a hole in the upper chambers of their heart known as patent foramen ovale (PFO), strokes of unknown cause were more strongly associated with nontraditional risk factors, such as migraines, liver disease or cancer, rather than more typical factors such as high blood pressure.

Migraine with aura was the top factor linked to strokes of unknown causes, also called cryptogenic strokes, especially among women.

Embargoed ...

Extreme drought contributed to barbarian invasion of late Roman Britain, tree-ring study reveals

2025-04-17

Three consecutive years of drought contributed to the ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’, a pivotal moment in the history of Roman Britain, a new Cambridge-led study reveals. Researchers argue that Picts, Scotti and Saxons took advantage of famine and societal breakdown caused by an extreme period of drought to inflict crushing blows on weakened Roman defences in 367 CE. While Rome eventually restored order, some historians argue that the province never fully recovered.

The ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’ of 367 CE was one of the most severe threats to Rome’s hold on Britain since the Boudiccan revolt three centuries earlier. Contemporary sources indicate that components ...

Antibiotic-resistant E. albertii on the rise in Bangladeshi chicken shops

2025-04-17

If you have ever chickened out of eating chicken, your unease may not have been unreasonable.

Osaka Metropolitan University researchers have detected alarming rates of Escherichia albertii, an emerging foodborne pathogen, in retail chicken meat in Bangladesh. Their findings show extensive contamination and significant antimicrobial resistance, underscoring the potential risks to public health.

E. albertii is a less known but probably not less dangerous relative of E. coli. First described in Bangladesh in 2003, this bacterium ...

Veterinary: UK dog owners prefer crossbreeds and imports to domestic pedigree breeds

2025-04-17

The UK pedigree dog population shrank by a yearly decline of 0.9% between 1990 and 2021, according to research published in Companion Animal Genetics and Health. The study highlights a rise in the populations of crossbreeds and imported pedigree dogs since 1990, but finds that only 13.7% of registered domestic pedigree dogs were used for breeding between 2005 and 2015.

There are more than 400 breeds of dogs globally, characterised by different appearances and behaviours. While the overall population of pet dogs in the UK ...

Study links climate change to rising arsenic levels in paddy rice, increasing health risks

2025-04-16

Climate change may significantly impact arsenic levels in paddy rice, a staple food for millions across Asia, reveals a new study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. The research shows that increased temperatures above 2°C, coupled with rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels, lead to higher concentrations of inorganic arsenic in rice, potentially raising lifetime health risks for populations in Asia by 2050. Until now, the combined effects of rising CO2 and temperatures on arsenic accumulation in rice have not been studied in detail. The research done ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

First evidence of WHO ‘critical priority’ fungal pathogen becoming more deadly when co-infected with tuberculosis

World-first safety guide for public use of AI health chatbots

Women may face heart attack risk with a lower plaque level than men

Proximity to nuclear power plants associated with increased cancer mortality

Women’s risk of major cardiac events emerges at lower coronary plaque burden compared to men

Peatland lakes in the Congo Basin release carbon that is thousands of years old

Breadcrumbs lead to fossil free production of everyday goods

New computation method for climate extremes: Researchers at the University of Graz reveal tenfold increase of heat over Europe

Does mental health affect mortality risk in adults with cancer?

EANM launches new award to accelerate alpha radioligand therapy research

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

[Press-News.org] New study reveals how cleft lip and cleft palate can ariseMIT biologists have found that defects in some transfer RNA molecules can lead to the formation of these common conditions