(Press-News.org) "Too simple" and "not so fast" suggest biological anthropologists from the George Washington University and New York University about the origins of human ancestry. In the upcoming issue of the journal Nature, the anthropologists question the claims that several prominent fossil discoveries made in the last decade are our human ancestors. Instead, the authors offer a more nuanced explanation of the fossils' place in the Tree of Life. They conclude that instead of being our ancestors the fossils more likely belong to extinct distant cousins.

"Don't get me wrong, these are all important finds," said co-author Bernard Wood, University Professor of Human Origins and professor of Human Evolution Anatomy at GW and director of its Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology. "But to simply assume that anything found in that time range has to be a human ancestor is naïve."

The paper, "The evolutionary context of the first hominins," reconsiders the evolutionary relationships of fossils named Orrorin, Sahelanthropus and Ardipithecus, dating from four to seven million years ago, which have been claimed to be the earliest human ancestors. Ardipithecus, commonly known as "Ardi," was discovered in Ethiopia and was found to be radically different from what many researchers had expected for an early human ancestor. Nonetheless, the scientists who made the discovery were adamant it is a human ancestor.

"We are not saying that these fossils are definitively not early human ancestors," said co-author Terry Harrison, a professor in NYU's Department of Anthropology and director of its Center for the Study of Human Origins. "But their status has been presumed rather than adequately demonstrated, and there are a number of alternative interpretations that are possible. We believe that it is just as likely or more likely that they are fossil apes situated close to the ancestry of the living great ape and humans."

The authors are skeptical about the interpretation of the discoveries and advocate a more nuanced approach to classifying the fossils. Wood and Harrison argue that it is naïve to assume that all fossils are the ancestors of creatures alive today and also note that shared morphology or homoplasy – the same characteristics seen in species of different ancestry – was not taken into account by the scientists who found and described the fossils. For example, the authors claim that for Ardipithecus to be a human ancestor, one must assume that homoplasy does not exist in our lineage, but is common in the lineages closest to ours. The authors suggest there are a number of potential interpretations of these fossils and that being a human ancestor is by no means the simplest, or most parsimonious explanation.

The scientific community has long concluded that the human lineage diverged from that of the chimpanzee six to eight million years ago. It is easy to differentiate between the fossils of a modern-day chimpanzee and a modern human. However, it is more difficult to differentiate between the two species when examining fossils that are closer to their common ancestor, as is the case with Orrorin, Sahelanthropus, and Ardipithecus.

In their paper, Wood and Harrison caution that history has shown how uncritical reliance on a few similarities between fossil apes and humans can lead to incorrect assumptions about evolutionary relationships. They point to the case of Ramapithecus, a species of fossil ape from south Asia, which was mistakenly assumed to be an early human ancestor in the 1960s and 1970s, but later found to be a close relative of the orangutan.

Similarly, Oreopithecus bambolii, a fossil ape from Italy shares many similarities with early human ancestors, including features of the skeleton that suggest that it may have been well adapted for walking on two legs. However, the authors observe, enough is known of its anatomy to show that it is a fossil ape that is only distantly related to humans, and that it acquired many "human-like" features in parallel.

Wood and Harrison point to the small canines in Ardipithecus and Sahelanthropus as possibly the most convincing evidence to support their status as early human ancestors. However, canine reduction was not unique to the human lineage for it occurred independently in several lineages of fossil apes (e.g., Oreopithecus, Ouranopithecus and Gigantopithecus) presumably as a result of similar shifts in dietary behavior.

###

EDITOR'S NOTE:

In the heart of the nation's capital with additional programs in Virginia, the George Washington University was created by an Act of Congress in 1821. Today, GW is the largest institution of higher education in the District of Columbia. The university offers comprehensive programs of undergraduate and graduate liberal arts study, as well as degree programs in medicine, public health, law, engineering, education, business and international affairs. Each year, GW enrolls a diverse population of undergraduate, graduate and professional students from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and more than 130 countries.

New York University, which was established in 1831, is one of the largest and most prestigious private research universities in the U.S. It has more international students than any other U.S. college or university. Through its 18 schools and colleges, NYU conducts research and provides education in the arts and sciences, law, medicine, dentistry, education, nursing, business, social work, the cinematic and performing arts, public administration and policy, and continuing studies, among other areas.

END

When doctors discover high concentrations of regulatory T cells in the tumors of breast cancer patients, the prognosis is often grim, though why exactly has long been unclear.

Now new research at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine suggests these regulatory T cells, whose job is to help mediate the body's immune response, produce a protein that appears to hasten and intensify the spread of breast cancer to distant organs and, in doing so, dramatically increase the risk of death.

The findings are reported in the Feb. 16 advance online edition ...

It has been long known that stress plays a part not just in the graying of hair but in hair loss as well. Over the years, numerous hair-restoration remedies have emerged, ranging from hucksters' "miracle solvents" to legitimate medications such as minoxidil. But even the best of these have shown limited effectiveness.

Now, a team led by researchers from UCLA and the Veterans Administration that was investigating how stress affects gastrointestinal function may have found a chemical compound that induces hair growth by blocking a stress-related hormone associated with ...

Montreal, February 16, 2011 – Recent studies conducted at the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) on a group of PCSK enzymes could have a positive impact on health, from cholesterol to osteoporosis. A team led by Dr. Nabil G. Seidah, Director of the Biochemical Neuroendocrinology research unit, has published six articles in prestigious scientific journals over the past four months, all shedding light on novel functions of certain PCSK enzymes.

PCSK enzymes belong to the proprotein convertase family, responsible for the conversion of an inactive protein ...

Researchers from the Department of Neurology at NYU Langone Medical Center identified potential benefits of a new computer application that automatically detects subtle brain lesions in MRI scans in patients with epilepsy. In a study published in the February 2011 issue of PLoS ONE, the authors discuss the software's potential to assist radiologists in better identifying and locating visually undetectable, operable lesions.

"Our method automatically identified abnormal areas in MRI scans in 92 percent of the patients sampled, which were previously identified by expert ...

LOS ANGELES – Increasing puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, the most abundant brain peptidase in mammals, slowed the damaging accumulation of tau proteins that are toxic to nerve cells and eventually lead to the neurofibrillary tangles, a major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, according to a study published online in the journal, Human Molecular Genetics.

Researchers found they could safely increase the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, PSA/NPEPPS, by two to three times the usual amount in animal models, and it removed the ...

Children with hip and thigh implants designed to help heal a broken bone or correct other bone conditions are at risk for subsequent fractures of the very bones that the implants were intended to treat, according to new research from Johns Hopkins Children's Center.

Findings of the Johns Hopkins study, based on an analysis of more than 7,500 pediatric bone implants performed at Hopkins over 15 years, will be presented Feb. 16 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Although the absolute risk among the patients was relatively small — nine ...

Scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute have begun to unravel how blood stem cells regenerate themselves, identifying a key gene required for the process.

The discovery that the Erg gene is vitally important to blood stem cells' unique ability to self-renew could give scientists new opportunities to use blood stem cells for tissue repair, transplantation and other therapeutic applications.

Professor Doug Hilton, Dr Samir Taoudi and colleagues from the institute's Molecular Medicine and Cancer and Haematology divisions led the study. Dr Taoudi said the research ...

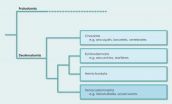

An international team of scientists including Albert Poustka from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin has discovered that Xenoturbellida and the acoelomorph worms, both simple marine worms, are more closely related to complex organisms like humans and sea urchins than was previously assumed. As a result they have made a major revision to the phylogenetic history of animals. Up to now, the acoelomate worms were viewed as the crucial link between simple animals like sponges and jellyfish and more complex organisms. It has now emerged that these animals ...

VIDEO:

To test their capacity to learn, the mice are trained to find an underwater platform which is not visible to them from the edge of a water basin. The swimming...

Click here for more information.

Amyloid-beta and tau protein deposits in the brain are characteristic features of Alzheimer disease. The effect on the hippocampus, the area of the brain that plays a central role in learning and memory, is particularly severe. However, it appears that the toxic effect of tau ...

Scientists have discovered that insects contain atomic clues as to the habitats in which they are most able to survive. The research has important implications for predicting the effects of climate change on the insects, which make up three-quarters of the animal kingdom.

Applying a method previously only used to examine the possible effects of climate change on plants, scientists from the University of Cambridge can now determine the climatic tolerances of individual insects. Their research was published today, 16 February, in the scientific journal Biology Letters.

Because ...