(Press-News.org) This release is available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and Chinese on EurekAlert! Chinese.

Several American black bears, captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after wandering a bit too close to human communities, have given researchers the opportunity to study hibernation in these large mammals like never before. Surprisingly, the new findings show that although black bears only reduce their body temperatures slightly during hibernation, their metabolic activity drops dramatically, slowing to about 25 percent of their normal, active rates.

This discovery was unexpected because, generally, an organism's chemical and biological processes are known to slow by approximately 50 percent for each 10 degree (Celsius) drop in body temperature. These Alaskan black bears only lowered their core body temperatures by five or six degrees, yet their metabolism slowed to rates much lower than researchers had imagined.

Furthermore, the black bears' metabolism remained significantly suppressed for several weeks after the animals emerged from their slumber.

Øivind Tøien and a group from the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, along with colleagues from Stanford University, will report their findings at the 2011 AAAS Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, on 17 February. Their study will also appear in the 18 February issue of Science, which is published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

Their study is the first to continuously measure the metabolic rates and body temperatures of black bears, or Ursus americanus, as they hibernated through the winter under natural conditions. The bears spend five to seven months without eating, drinking, urinating or defecating before they emerge from their dens in nearly the same physiological condition they were in when they entered them. This feat leads researchers to believe that, in the future, the data collected in this study might be applied to a very wide range of endeavors – from improving medical care to pioneering deep space travel.

The black, furry study participants, who had been deemed nuisance bears by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, were transported to the Institute of Arctic Biology where they were placed in structures designed to mimic a bear's den. These dens were located in the woods, away from human disturbances, and equipped with infrared cameras, activity detectors and other remote sensing devices. Tøien and his colleagues also implanted radio transmitters into each bear to record the animals' body temperatures, heart beats and muscle activity.

By monitoring the black bears, day and night for five months of hibernation, the researchers observed that the bears' body temperatures fluctuated between 30 and 36 degrees Celsius in slow two- to seven-day cycles. Such large, multi-day fluctuations in core body temperature are unlike those observed in any other hibernators before.

One female black bear that was pregnant during her hibernation maintained a normal, wakeful body temperature throughout the pregnancy – a detail that implies fluctuating temperature cycles may not be favorable for embryonic development. After she birthed her cub (who unfortunately died due to a congenital diaphragmatic hernia), the female bear's body temperature began to fall and it eventually joined the variable cycle that the other hibernating bears experienced.

"A very important clue to understand what is going on with the bear's metabolism is their body temperatures," Tøien said. "We knew that bears decreased their body temperatures to some degree during hibernation, but in Alaska we found that these black bears regulate their core temperature in variable cycles over a period of many days, which is not seen in smaller hibernators and which we are not aware has been seen in mammals at all before."

Once the bears' core body temperatures dropped to about 30 degrees Celsius, they were observed to shiver until their temperatures reached about 36 degrees Celsius, which often took several days. Then the bears reduced shivering until their body temperature again fell to about 30 degrees Celsius, and the cycle began again.

By measuring how much oxygen the creatures consumed while hibernating in the mock dens, the researchers could glean that the bears reduced their metabolic rates by 75 percent compared to their summertime levels. The animals' heart rates also slowed from around 55 beats per minute to about 14 beats per minute.

"Sinus arrhythmia is a variation in heartbeat frequency relative to breathing, and the bears show an extreme form of this," said Tøien. "They have an almost-normal heartbeat when they take a breath. But, between breaths, the bears' hearts beat very slowly. Sometimes, there is as much as 20 seconds between beats. Each time the bear takes a breath its heart accelerates for a short time to almost that of a resting bear in summer. When the bear breathes out, the heart slows down again…"

In spring, when the bears awoke and emerged from their dens, the researchers had expected to find the animals' metabolism returning to normal levels right away. But, the team was again surprised to find that the bears' metabolic rates were still only half of their normal, summer levels. Tøien and his team continued to monitor the bears' metabolism for another month after their hibernation and determined that the bears did not return to their active metabolic activity for two to three full weeks.

Taken together, these findings paint a unique picture of hibernation in a human-sized mammal – and researchers hope to apply them in a wide range of disciplines. Since some form of hibernation – in which body temperature and metabolism are reduced – has been observed in nine orders of mammals, it is likely that the genetic basis for this ability is ancient and widespread and that it could be exploited for various purposes. "If our research could help by showing how to reduce metabolic rates and oxygen demands in human tissues, one could possibly save people," Tøien said. "We simply need to learn how to turn things on and off to induce states that take advantage of the different levels of hibernation."

"When black bears emerge from hibernation in spring, it has been shown that they have not suffered the losses in muscle and bone mass and function that would be expected to occur in humans over such a long time of immobility and disuse," continued Brian Barnes, the senior author of the study. "If we could discover the genetic and molecular basis for this protection, and for the mechanisms that underlie the reduction in metabolic demand, there is the possibility that we could derive new therapies and medicines to use on humans to prevent osteoporosis, disuse atrophy of muscle, or even to place injured people in a type of suspended or reduced animation until they can be delivered to advanced medical care – extending the golden hour to a golden day or a golden week."

Hibernation could also become relevant for deep space travel, researchers say. If the human race is ever able to leave Earth as a species, it might be necessary to induce a bear-like hibernation in order to make the trip into deep space possible.

Of course, these possibilities will require much more research in order to achieve them.

INFORMATION:

This report by Tøien et al. was funded by a U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grant, grants from the National Science Foundation, a grant from the National Institutes of Health, gift funds to Stanford University, the American Heart Association and the Fulbright Program.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is the world's largest general scientific society, and publisher of the journal, Science (www.sciencemag.org) as well as Science Translational Medicine (www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org) and Science Signaling (www.sciencesignaling.org). AAAS was founded in 1848, and includes some 262 affiliated societies and academies of science, serving 10 million individuals. Science has the largest paid circulation of any peer-reviewed general science journal in the world, with an estimated total readership of 1 million. The non-profit AAAS (www.aaas.org) is open to all and fulfills its mission to "advance science and serve society" through initiatives in science policy; international programs; science education; and more. For the latest research news, log onto EurekAlert!, www.eurekalert.org, the premier science-news Web site, a service of AAAS.

Bears uncouple temperature and metabolism for hibernation, new study shows

Sharp decline in metabolic activity persists for weeks after waking

2011-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

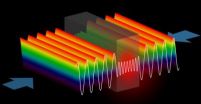

Scientists build world's first anti-laser

2011-02-18

New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light ...

The real avatar

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

Taking brain-computer interfaces to the next phase

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...

Skeleton regulates male fertility

2011-02-18

NEW YORK (February 17, 2011) – Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center have discovered that the skeleton acts as a regulator of fertility in male mice through a hormone released by bone, known as osteocalcin.

The research, led by Gerard Karsenty, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, is slated to appear online on February 17 in Cell, ahead of the journal's print edition, scheduled for March 4.

Until now, interactions between bone and the reproductive system have focused only on the influence ...

Put major government policy options through a science test first, biodiversity experts urge

2011-02-18

Scientific advice on the consequences of specific policy options confronting government decision makers is key to managing global biodiversity change.

That's the view of leading scientists anxiously anticipating the first meeting of a new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-like mechanism for biodiversity at which its workings and work program will be defined.

Writing in the journal Science, the scientists say the new mechanism, called the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), should adopt a modified working approach ...

Subtle shifts, not major sweeps, drove human evolution

2011-02-18

The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds.

Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species.

By examining the sequences of nearly ...

Dr. Todd Kuiken, pioneer of bionic arm control at RIC, to present latest advances at AAAS meeting

2011-02-18

VIDEO:

Glen Lehman discusses his research.

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON (February 17) –Todd Kuiken, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the Center for Bionic Medicine and Director of Amputee Services at The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), designated the "#1 Rehabilitation Hospital in America" by U.S. News & World Report since 1991, will present the latest in Targeted Muscle Reinnervation (TMR), a bionic limb technology, during the opening press briefing and ...

Policy experts say changes in expectations and funding key to genomic medicine's future

2011-02-18

INDIANAPOLIS – Unrealistic expectations about genomic medicine have created a "bubble" that needs deflating before it puts the field's long term benefits at risk, four policy experts write in the current issue of the journal Science.

Ten years after the deciphering of the human genetic code was accompanied by over-hyped promises of medical breakthroughs, it may be time to reevaluate funding priorities to better understand how to change behaviors and reap the health benefits that would result.

In addition, the authors say, scientists need to foster more realistic understanding ...

Scientists uncover surprising features of bear hibernation

2011-02-18

Fairbanks, ALASKA—Black bears show surprisingly large and previously unobserved decreases in their metabolism during and after hibernation according to a paper by scientists at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and published in the 18 February issue of the journal Science.

"In general, an animal's metabolism slows to about half for each 10 degree (Celsius) drop in body temperature. Black bears' metabolism slowed by 75 percent, but their core body temperature decreased by only five to six degrees," said Øivind Tøien, IAB research scientist ...

Flocculent spiral NGC 2841

2011-02-18

Star formation is one of the most important processes in shaping the Universe; it plays a pivotal role in the evolution of galaxies and it is also in the earliest stages of star formation that planetary systems first appear.

Yet there is still much that astronomers don't understand, such as how do the properties of stellar nurseries vary according to the composition and density of the gas present, and what triggers star formation in the first place? The driving force behind star formation is particularly unclear for a type of galaxy called a flocculent spiral, such as ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

[Press-News.org] Bears uncouple temperature and metabolism for hibernation, new study showsSharp decline in metabolic activity persists for weeks after waking