(Press-News.org) BETHESDA, Md., Feb. 28, 2011 – Science fiction novelist and scholar Issac Asimov once said, "The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not 'Eureka!' but 'That's funny.' " This recently rang true for an international team of researchers when they observed something they did not expect.

In a Journal of Biological Chemistry "Paper of the Week," the Berlin-based team reports that it has uncovered surprising new details about a key protein-protein interaction in the retina that contributes to the exquisite sensitivity of vision. Additionally, they say, the proteins involved represent the best-studied model of how other senses and countless other physiological functions are controlled.

"Nearly a thousand different types of these proteins are present in the human body, and nearly half of pharmaceutical drugs are targeted to them," explains Martha E. Sommer, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Medicinal Physics and Biophysics at Charité Medical School and the first author on the JBC paper.

The retina, which is located at the back of the eye, is considered an outgrowth of the brain and is, thus, a part of the central nervous system. Embedded in the retina's 150 million rod-shaped photoreceptor cells are purplish pigment molecules called rhodopsin. It is the rhodopsin protein that is activated by the first glimmer – or photon – of light. Upon activation, the purple molecule binds another protein, known as transducin, to set off a cascade of biochemical reactions that ultimately results in vision.

"After this signaling event, rhodopsin must be shut off. This task is achieved by a third molecule called arrestin, which binds to light-activated rhodopsin and blocks further signaling," Sommer says. When rhodopsin is not properly shut off, overactive signaling can lead to a decrease in sensitivity to light and ultimately cell death. People who lack arrestin have a form of night blindness called Oguchi disease. "They are essentially blind in low light and can suffer retinal degeneration over time."

It is believed that the arrestin molecule silences rhodopsin's signaling by embracing it and elbowing out transducin.

"Since arrestin was first discovered more than 20 years ago, it was assumed that a single arrestin binds a single light-activated rhodopsin," Sommer says. "However, when the molecular structure of arrestin was solved using X-ray crystallography about 10 years ago, it was observed that arrestin is composed of two near-symmetrical parts – like an open clam shell."

The diameter of each side of the arrestin shell is about equal to that of one rhodopsin, she says, so some researchers wondered if a single arrestin might be able to bind to two rhodopsins.

It seemed like a simple enough question: To how many rhodopsins can a single arrestin bind? But, Sommer explains, little experimental work had been published about the topic, and the few studies that had been done seemed to support the one-arrestin-to-one-rhodopsin theory. That is, until now.

Using photoreceptor cells from cows, Sommer's team set out to shine a light on the rhodopsin-arrestin mystery once and for all. They exposed the rhodopsin molecules to low light and to bright light and managed to count how many arrestin molecules bound with them. In the end, it took three to tango.

"Increasing the light intensity increases the percentage of rhodopsins that are activated. Although the number of arrestins that bound per activated rhodopsin appeared to change with the percentage of activated rhodopsins -- with one-to-one binding in very low light and one-to-two binding in very bright light -- we hypothesize that arrestin always interacts with two rhodopsin molecules," Sommer says. "In low light, arrestin interacts with one active rhodopsin and with one inactive rhodopsin; whereas, in bright light, arrestin interacts with two active rhodopsins."

It's just a matter of probability, Sommer says: In brighter light, arrestin interacts with two activated receptors simply because there are more of them around.

"Although there were two fairly clear-cut theories regarding how arrestin binds rhodopsin, what was totally unexpected is that both can occur," she says.

But, what does this mean for the other senses and physiological functions controlled by other rhodopsin-like proteins? Rhodopsin is the most-studied member of the large family of G-protein coupled receptors, or GPCRs, and many well-known drugs target GPCRs. For example, when morphine binds to a GPCR, it affects the release of neurotransmitters in the brain and thus reduces pain signals. Meanwhile, beta-blockers, which are used to treat cardiac conditions and hypertension, block the activation of GPCRs by standing in the way of natural activating molecules.

"Nearly all GPCRs are normally bound by arrestin, and arrestin can greatly influence what happens to the GPCRs when they are acted on by drugs," says Sommer. "For example, many GPCR-targeted drugs become less effective with continued use. Part of this is because of arrestin. Arrestin binds to the activated GPCR and tells the cell to remove it from the cell surface. In other words, arrestin causes the cell to become less sensitive to the drug because it loses the receptors that normally catch the drug molecules."

By understanding how arrestin interacts with receptors like rhodopsin under healthy conditions, she says, researchers will be able to design better drugs that avoid such problems as desensitization.

INFORMATION:

Sommer made these discoveries with Professor Klaus Peter Hofmann and Martin Heck, both of the Institute for Medicinal Physics and Biophysics at the Charité Medical University. In 2007 the National Science Foundation awarded Sommer an international research fellowship that sponsored her move to Germany and subsequent collaborative research. The work was also funded by the German-based Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the largest research-funding organization in Europe.

The resulting "Paper of the Week" appears in the March 4 print issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

About the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

The ASBMB is a nonprofit scientific and educational organization with more than 12,000 members worldwide. Most members teach and conduct research at colleges and universities. Others conduct research in various government laboratories, at nonprofit research institutions and in industry. The Society's student members attend undergraduate or graduate institutions. For more information about ASBMB, visit www.asbmb.org.

Researchers develop curious snapshot of powerful retinal pigment and its partners

Three's not a crowd when it comes to triggering the senses and other physiological functions

2011-03-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Full bladder, better decisions? Controlling your bladder decreases impulsive choices

2011-03-01

What should you do when you really, REALLY have to "go"? Make important life decisions, maybe. Controlling your bladder makes you better at controlling yourself when making decisions about your future, too, according to a study to be published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Sexual excitement, hunger, thirst—psychological scientists have found that activation of just one of these bodily desires can actually make people want other, seemingly unrelated, rewards more. Take, for example, a man who finds himself searching ...

MIT-- parts of brain can switch functions

2011-03-01

Cambridge, MASS- When your brain encounters sensory stimuli, such as the scent of your morning coffee or the sound of a honking car, that input gets shuttled to the appropriate brain region for analysis. The coffee aroma goes to the olfactory cortex, while sounds are processed in the auditory cortex.

That division of labor suggests that the brain's structure follows a predetermined, genetic blueprint. However, evidence is mounting that brain regions can take over functions they were not genetically destined to perform. In a landmark 1996 study of people blinded early ...

Gut bacteria can control organ functions

2011-03-01

Bacteria in the human gut may not just be helping digest food but also could be exerting some level of control over the metabolic functions of other organs, like the liver, according to research published this week in the online journal mBio®. These findings offer new understanding of the symbiotic relationship between humans and their gut microbes and how changes to the microbiota can impact overall health.

"The gut microbiota enhances the host's metabolic capacity for processing nutrients and drugs and modulates the activities of multiple pathways in a variety of organ ...

Mating mites trapped in amber reveal sex role reversal

2011-03-01

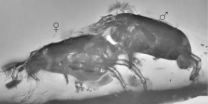

ANN ARBOR, Mich.---In the mating game, some female mites are mightier than their mates, new research at the University of Michigan and the Russian Academy of Sciences suggests. The evidence comes, in part, from 40 million-year-old mating mites preserved in Baltic amber.

In a paper published March 1 in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, researchers Pavel Klimov and Ekaterina Sidorchuk describe an extinct mite species in which the traditional sex roles were reversed.

"In this species, it is the female who has partial or complete control of mating," said Klimov, ...

Dry lake reveals evidence of southwestern 'megadroughts'

2011-03-01

LOS ALAMOS, New Mexico, February 28, 2011—There's an old saying that if you don't like the weather in New Mexico, wait five minutes. Maybe it should be amended to 10,000 years, according to new research.

In a letter published recently in the journal Nature, Los Alamos National Laboratory researchers and an international team of scientists report that the Southwest region of the United States undergoes "megadroughts"—warmer, more arid periods lasting hundreds of years or longer. More significantly, a portion of the research indicates that an ancient period of warming may ...

Silk moth's antenna inspires new nanotech tool with applications in Alzheimer's research

2011-03-01

ANN ARBOR, Mich.---By mimicking the structure of the silk moth's antenna, University of Michigan researchers led the development of a better nanopore---a tiny tunnel-shaped tool that could advance understanding of a class of neurodegenerative diseases that includes Alzheimer's.

A paper on the work is newly published online in Nature Nanotechnology. This project is headed by Michael Mayer, an associate professor in the U-M departments of Biomedical Engineering and Chemical Engineering. Also collaborating are Jerry Yang, an associate professor at the University of California, ...

Neighborhood barbers can influence black men to seek blood-pressure treatment

2011-03-01

DALLAS – March 1, 2011 – Will Marshall saw a physician about his blood pressure at his barber's urging.

Yes, his barber.

"The barber and beauty shops for men and women are kind of their own private escapes," Mr. Marshall said. "Every conversation you can imagine goes on in the barbershop. I wouldn't have put the barbershop and blood pressure together – but that visit to my physician for my blood pressure saved my life."

Mr. Marshall now has a healthy blood pressure thanks to lifestyle and dietary changes.

He is one of about 1,300 participants in a study described ...

Researchers looking at a rare disease make breakthrough that could benefit everyone

2011-03-01

This release is available in French.

MONTREAL, March 1, 2011 – By working with Canadians of French ancestry who suffer a rare genetic disease, researchers have discovered how three genes contribute to abnormal growth, making a breakthrough that will improve our understanding of many disorders such as foetal and childhood growth retardation, abnormal development of body parts and cancer. "As a result of the Human Genome Project, we know the basic identity of essentially all the genes in the human body, but we don't automatically know what they do in detail," explained ...

Quality of life significantly increases after uterine fibroid treatment

2011-03-01

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Women who received one of three treatments for uterine fibroids at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston said their symptoms diminished and their quality of life significantly increased, according to a new study published in the May issue of Radiology.

Uterine fibroids are benign pelvic tumors that occur in as many as one in five women during their childbearing years. Although not all fibroids cause symptoms, some women experience heavy bleeding, pain and infertility. Treatment options include hysterectomy, minimally invasive uterine artery embolization ...

Hospital use of virtual colonoscopy is on the rise, study suggests

2011-03-01

Reston, VA (Feb. 23, 2011) — Despite the absence of Medicare coverage, hospital use of computed tomographic colonography (CTC), commonly referred to as virtual colonoscopy, is on the rise, according to a study in the March issue of the Journal of the American College of Radiology (www.jacr.org). Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the U.S. CTC, a minimally invasive alternative to optical colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, employs virtual reality technology to produce a 3-D visualization that permits a thorough evaluation of the entire ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

International research team solves mystery behind rare clotting after adenoviral vaccines or natural adenovirus infection

The most common causes of maternal death may surprise you

A new roadmap spotlights aging as key to advancing research in Parkinson’s disease

Research alert: Airborne toxins trigger a unique form of chronic sinus disease in veterans

University of Houston professor elected to National Academy of Engineering

UVM develops new framework to transform national flood prediction

Study pairs key air pollutants with home addresses to track progression of lost mobility through disability

Keeping your mind active throughout life associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk

TBI of any severity associated with greater chance of work disability

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

What honey bee brain chemistry tells us about human learning

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

Twilight fish study reveals unique hybrid eye cells

Could light-powered computers reduce AI’s energy use?

Rebuilding trust in global climate mitigation scenarios

Skeleton ‘gatekeeper’ lining brain cells could guard against Alzheimer’s

HPV cancer vaccine slows tumor growth, extends survival in preclinical model

How blood biomarkers can predict trauma patient recovery days in advance

People from low-income communities smoke more, are more addicted and are less likely to quit

No association between mRNA COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and autism in children, new research shows

[Press-News.org] Researchers develop curious snapshot of powerful retinal pigment and its partnersThree's not a crowd when it comes to triggering the senses and other physiological functions