(Press-News.org) The tendency to perceive others as "us versus them" isn't exclusively human but appears to be shared by our primate cousins, a new study led by Yale researchers has found.

In a series of ingenious experiments, Yale researchers led by psychologist Laurie Santos showed that monkeys treat individuals from outside their groups with the same suspicion and dislike as their human cousins tend to treat outsiders, suggesting that the roots of human intergroup conflict may be evolutionarily quite ancient.

The findings are reported in the March issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

"One of the more troubling aspects of human nature is that we evaluate people differently depending on whether they're a member of our 'ingroup' or 'outgroup,'" Santos said. "Pretty much every conflict in human history has involved people making distinctions on the basis of who is a member of their own race, religion, social class, and so on. The question we were interested in is: Where do these types of group distinctions come from?"

The answer, she adds, is that such biases have apparently been shaped by 25 million years of evolution and not just by human culture.

Santos and her lab studied the rhesus macaques living on an island off the coast of Puerto Rico. Like humans, monkeys in this population naturally form different social groups on the basis of family history. In order to assess whether monkeys made the same distinctions between ingroup and outgroup individuals, the researchers used a well-known tendency of animals to stare longer at novel or frightening things than at familiar or friendly things. They presented subject monkeys with pictures of monkeys who were either in their social group or members of a different group. They found that monkeys stared longer at pictures of other monkeys who were outside their group, suggesting that monkeys spontaneously detect who is a stranger and who is a group member.

"What made this result even more remarkable" noted Neha Mahajan, a Yale graduate student who headed up this project, "is that monkeys in this population move around from group to group, so some of the monkeys who were 'outgroup' were previously 'ingroup.' And yet, the result holds just as strongly for monkeys who have transferred groups only weeks earlier, suggesting that these monkeys are sensitive to who is currently to be thought of as an insider or an outsider. In other words, although monkeys divide the world into 'us' versus 'them,' they do so in a way that is flexible and is updated in real time."

Santos and colleagues then asked whether monkeys evaluated ingroup and outgroup members differently – did they associate these individuals automatically with "good" and "bad" respectively? To study this, they developed a monkey version of a test of implicit attitudes known as the IAT (see http://implicit.harvard.edu). In humans, this test measures the extent to which people show implicit biases against members of other groups. To look at the same capacity in monkeys, the researchers showed monkeys a sequence of photos in which photos of ingroup or outgroup monkey faces were paired with photos of either good things, such as fruits, or bad things, such as spiders. The researchers then recorded the time monkeys spent looking at both kinds of sequences. The monkeys spent little time looking at sequences that included ingroup faces paired with good stuff like fruits or outgroup faces paired with bad stuff like spiders, suggesting that the monkeys treated these two kinds of stimuli as being similar. On the other hand, the monkeys stared longer at sequences in which outgroup individuals were paired with positive objects like fruit suggesting that this association was unnatural to the monkeys. Like humans, monkeys tend to spontaneously view ingroup members positively and outgroup members negatively.

The Yale team's results suggest that the distinctions humans make between "us" and "them"— and therefore the roots of human prejudice—may date back at least 25 million years, when humans and rhesus macaques shared a common ancestor.

"Social psychologists introduced the world to the idea that the immediate situation is hugely powerful in determining behavior, even intergroup feelings," said Mahzarin Banaji, of the Department of Psychology at Harvard University and a co-author of the paper. "Evolutionary theorists have made us aware of our ancestral past. In this work, we weave the two together to show the importance of both of these influences at work"

"The bad news is that the tendency to dislike outgroup members appears to be evolutionarily quite old, and therefore may be less simple to eliminate than we'd like to think," Santos said. "The good news, though, is that even monkeys seem to be flexible about who counts as a group member. If we humans can find ways to harness this evolved flexibility, it might allow us to become an even more tolerant species."

INFORMATION:

Other Yale authors of the paper are Margaret A. Martinez and Natashya Gutierrez. Researchers from Bar-Ilan University and Harvard also contributed to the study.

The work was funded the National Center for Research Resources, part of the National Institutes of Health.

END

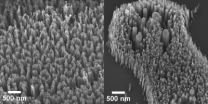

Carbon nanofibers hold promise for technologies ranging from medical imaging devices to precise scientific measurement tools, but the time and expense associated with uniformly creating nanofibers of the correct size has been an obstacle – until now. A new study from North Carolina State University demonstrates an improved method for creating carbon nanofibers of specific sizes, as well as explaining the science behind the method.

"Carbon nanofibers have a host of potential applications, but their utility is affected by their diameter – and controlling the diameter of ...

Badbeat.com, the original and leading online poker staking business, will be donating 10% of ALL affiliate revenue generated by the Badbeat players on Friday 18th March to Comic Relief in support of Red Nose Day.

The Badbeat management has urged their players to help change lives both in the UK and across Africa, challenging them to raise as much money as possible playing poker day and night!

"Red Nose Day is a day like no other; when the whole country gets together to help change countless lives," said Badbeat Managing Director, John Conroy. "We're incredibly happy ...

MIAMI – March 17, 2010 -- University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science scientist Chris Langdon and colleagues developed a new tool to monitor coral reef vital signs. By accurately measuring their biological pulse, scientists can better assess how climate change and other ecological threats impact coral reef health worldwide.

During a March 2009 experiment at Cayo Enrique Reef in Puerto Rico, the team tested two new methods to monitor biological productivity. They compared a technique that measures changes in dissolved oxygen within ...

Using skin cells from adult siblings with schizophrenia and a genetic mutation linked to major mental illnesses, Johns Hopkins researchers have created induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) using a new and improved "clean" technique.

Reporting online February 22 in Molecular Psychiatry, the team confirms the establishment of two new lines of iPS cells with mutations in the gene named Disrupted In Schizophrenia 1, or DISC1. They made the cells using a nonviral "epiosomal vector" that jumpstarts the reprogramming machinery of cells without modifying their original ...

Researchers at the University of Granada have proved that neuropsychological rehabilitation helps in significantly reducing cognitive, emotional and behavioural after-effects in patients with acquired brain injury, generaly due to traumatic brain injury and ictus. These patients should not wait to be treated later by the social services, since early intervention (within six months after the traumatism) reduces further after-effects.

Despite the prevention campaigns launched for reducing traffic accidents and improving heart-friendly habits, traumatic brain injury and ...

A pilot study in healthy children and adolescents shows that it is feasible to screen for undiagnosed heart conditions that increase the risk of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). Adding a 10-minute electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) to a history and physical examination identified unsuspected cases of potentially serious heart conditions.

Although more research is needed, the preliminary results suggest that a relatively low-cost screening might help identify children who are at risk for sudden cardiac arrest, possibly preventing childhood death.

"In the United States, the ...

Halifax Savings research has shown that children in Wales have the highest ownership levels of games consoles and mobile phones across the nation and also spend the most amount of money on computer games and equipment.

They also do extremely well when it comes to owning an iPod or MP3 player and only fall down slightly on music downloads and mobile phone expenditure.

A full house for Welsh gamers

100% of the children surveyed in Wales owned a games console, well above the national average of 91%.

Children in Wales also spent the highest amount of money on computer ...

Washington, D.C. (March 17, 2011) -- A team of researchers has integrated tiny detectors capable of counting individual photons on computer chips. These detectors, called "single-photon avalanche diodes (SPAD)," act like mini Geiger counters, producing a "tick" each time a photon is detected.

The researchers present their findings in Applied Physics Letters, a journal published by the American Institute of Physics.

"In the past, making these detectors required specialized processes, but recently there has been tremendous progress in making these devices in 'standard' ...

Researchers working in a research project within the Academy of Finland's Research Programme on Substance Use and Addictions have been developing a targeted drug that could aid in smoking reduction therapy. The new drug slows down the metabolism of nicotine, which would help smokers to cut down their smoking.

Nicotine is absorbed rapidly through the lining of the mouth but most readily through the lungs, from where it quickly passes through the body and into the brain. Once the nicotine reaches the liver, it is metabolised by an enzyme called CYP2A6. Preliminary studies ...

Radioactive waste decaying down at the dump needs millions of years to stabilize. The element Neptunium, a waste product from uranium reactors, could pose an especially serious health risk should it ever seep its way into groundwater – even 5 million years after its deposition. Now, researchers at the University of Copenhagen have shown the hazardous waste can be captured and contained. The means? A particular kind of green goop that occurs naturally in oxygen-poor water.

Bo C. Christiansen is a geochemist at the University of Copenhagen who specializes in "green rust". ...