Strategy discovered to prevent Alzheimer's-associated traffic jams in the brain

Tau reduction prevents amyloid proteins from disrupting transport of vital cargoes between brain cells

2010-09-10

(Press-News.org) SAN FRANCISCO, CA – September 9, 2010 – Amyloid beta (Αβ) proteins, widely thought to cause Alzheimer's disease (AD), block the transport of vital cargoes inside brain cells. Scientists at the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease (GIND) have discovered that reducing the level of another protein, tau, can prevent Aβ from causing such traffic jams.

Neurons in the brain are connected to many other neurons through long processes called axons. Their functions depend on the transport of diverse cargoes up and down these important pipelines. Particularly important among the cargoes are mitochondria, the energy factories of the cell, and proteins that support cell growth and survival. Aβ proteins, which build up to toxic levels in the brains of people with AD, impair the axonal transport of these cargoes.

"We previously showed that suppressing the protein tau can prevent Aβ from causing memory deficits and other abnormalities in mouse models of AD," explained Lennart Mucke, MD, GIND director and senior author of the study. "We wondered whether this striking rescue might be caused, at least in part, by improvements in axonal transport."

The scientists explored this possibility in mouse neurons grown in culture dishes. Neurons from normal mice or from mice lacking one or both tau genes were exposed to human Aβ proteins. The Aβ slowed down axonal transport of mitochondria and growth factor receptors, but only in neurons that produced tau and not in neurons that lacked tau. In the absence of the Aβ challenge, tau reduction had no effect on axonal transport.

"We are really excited about these results," said Keith Vossel, MD, lead author of the study. "Whether tau affects axonal transport or not has been a controversial issue, and nobody knew how to prevent Aβ from impairing this important function of neurons. Our study shows that tau reduction accomplishes this feat very effectively."

"Some treatments based on attacking Aβ have recently failed in clinical trials, and so, it is important to develop new strategies that could make the brain more resistant to Aβ and other AD-causing factors," said Dr. Mucke. "Tau reduction looks promising in this regard, although a lot more work needs to be done before such approaches can be explored in humans."

INFORMATION:

The team also included Gladstone's Jens Brodbeck, Aaron Daub, Punita Sharma, and Steven Finkbeiner. Kai Zhang and Bianxiao Cui of Stanford's chemistry department also contributed to the research.

The NIH and the McBean Family Foundation supported this work.

Lennart Mucke's primary affiliation is with the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease, where he is Director/Senior Investigator and where his laboratory is located and his research is conducted. He is also the Joseph B. Martin Distinguished Professor of Neuroscience at UCSF.

The Gladstone Institutes is a nonprofit, independent research and educational institution, consisting of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology, and the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. Independent in its governance, finances and research programs, Gladstone shares a close affiliation with UCSF through its faculty, who hold joint UCSF appointments.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2010-09-10

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified "secondary over-triage" as a potential area of cost savings for our nation's health care. The phenomenon of over-triage occurs when patients are transferred twice, and discharged from a second facility in less than 24 hours. These findings will be published in the September 10th issue of The Journal of Trauma.

"By looking at the number of times patients are transferred, we can evaluate the overall efficiency of our trauma system and its impact on healthcare costs," said Hayley Osen, ...

2010-09-10

We're all familiar with birds that are as comfortable diving as they are flying but only one family of fish has made the reverse journey. Flying fish can remain airborne for over 40s, covering distances of up to 400m at speeds of 70km/h. Haecheon Choi, a mechanical engineer from Seoul National University, Korea, became fascinated by flying fish when reading a science book to his children. Realising that flying fish really do fly, he and his colleague, Hyungmin Park, decided to find out how these unexpected fliers stay aloft and publish their discovery that flying fish glide ...

2010-09-10

Disparities in healthcare between races exist in the United States. A new study published in the journal Transfusion explores why African Americans donate blood at lower rates than whites. The findings reveal that there is a significant distrust in the healthcare system among the African American community, and African Americans who distrust hospitals are less likely to donate.

Led by Beth H. Shaz, MD, Chief Medical Officer of the New York Blood Center in New York, New York, researchers created a survey to explore reasons for low likelihood of blood donation in African ...

2010-09-10

BEKTV utilizing industry leading service assurance tool to gain viewership insight

Fiber to the Home (FTTH) Conference, Las Vegas, NV, September 9th, 2010: BEK Communications, the innovative telecommunications company serving south-central North Dakota, announced today their use of xVu as a means of gaining improved insight of their local programming. A key element of BEK's strategy as a multi-faceted telecom company is their exclusive hometown programming. Through BEKTV, BEK Communications broadcasts such specialized local features as BEK Sports, BEK Life and BEK Local ...

2010-09-09

Bowerbird males are well known for making elaborate constructions, lavished with decorative objects, to impress and attract their mates. Now, researchers reporting online on September 9 in Current Biology, a Cell Press journal, have identified a completely new dimension to these showy structures in great bowerbirds. The birds create a staged scene, only visible from the point of view of their female audience, by placing pebbles, bones, and shells around their courts in a very special way that can make objects (or a bowerbird male) appear larger or smaller than they really ...

2010-09-09

Five minutes in a scanner can reveal how far a child's brain has come along the path from childhood to maturity and potentially shed light on a range of psychological and developmental disorders, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown.

Researchers assert this week in Science that their study proves brain imaging data can offer more extensive help in tracking aberrant brain development.

"Pediatricians regularly plot where their patients are in terms of height, weight and other measures, and then match these up to standardized curves ...

2010-09-09

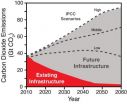

Stanford, CA— Scientists have warned that avoiding dangerous climate change this century will require steep cuts in carbon dioxide emissions. New energy-efficient or carbon-free technologies can help, but what about the power plants, cars, trucks, and other fossil-fuel-burning devices already in operation? Unless forced into early retirement, they will emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere for decades to come. Will their emissions push carbon dioxide levels beyond prescribed limits, regardless of what we build next? Is there already too much inertia in the system to curb ...

2010-09-09

Laxenburg, Austria – 9th September 2010. Due to increasing life-spans and improved health many populations are 'aging' more slowly than conventional measures indicate.

In a new study, to be published in Science, (10 September) scientists from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Austria, Stony Brook University, US, (SBU), and the Vienna Institute of Demography (VID) have developed new measures of aging that take changes in disability status and longevity into account.

The results give policymakers faced with growing numbers of elderly ...

2010-09-09

Current energy technologies are not enough to reduce carbon emissions to a level needed to lower the risks associated with climate change, New York University physicist Martin Hoffert concludes in an essay in the latest issue of the journal Science.

Many scientists have determined that in order to avoid the risks brought about by climate change, steps must be taken to prevent the mean global temperature from rising by more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Current climate models indicate that achieving this goal will require limiting atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) ...

2010-09-09

An innovative grouping of conservation scientists and practitioners have come together to advocate a fundamental shift in the way we view biodiversity. In their paper, which was published today in the journal Science, they argue that unless people recognise the link between their consumption choices and biodiversity loss, the diversity of life on Earth will continue to decline.

Dr Mike Rands, Director of the Cambridge Conservation Initiative and lead author of the paper, said: "Despite increasing worldwide conservation efforts, biodiversity continues to decline. If ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Strategy discovered to prevent Alzheimer's-associated traffic jams in the brain

Tau reduction prevents amyloid proteins from disrupting transport of vital cargoes between brain cells