Michael Pasquier, assistant professor of religious studies and historian at LSU, has developed "Standard Lives: Visualizing the Culture of Oil in Louisiana." The goal of this project is to complement scientific investigations of the Deepwater Horizon disaster by documenting the cultural impact of environmental stressors on Louisiana's coastal communities.

"To do this, it's necessary to look at oil from 'the ground up,' so to speak," said Pasquier. "I knew we needed to take a long and unbiased look at Louisiana's relationship with the oil industry, and by extension, its effects on the everyday lives of refinery and offshore workers, as well as the businessmen, teachers, farmers, fishermen, mariners, homemakers and others with direct and indirect ties to petroleum-based services."

Pasquier started his project by delving into a photo collection at the University of Louisville that showcased in detail how the industry fundamentally transformed the social and environmental landscape of Louisiana at mid-century.

In 1943, Standard Oil hired Roy Stryker, famous for directing the United States government's Farm Security Administration photography project during the Great Depression to organize a team of photographers to document the "benefits of oil on the everyday lives of Americans." Standard Oil executives intended for the photographs to function as a visual source of advertisement and public relations for the company. That being said, the propagandistic qualities of the project were not lost to Stryker and his photographers.

At that time, much of the oil industry was already located in Southern Louisiana, an area replete with natural resources – and poverty. The Standard Oil Collection, spanning some 100,000 photographs, many of which were taken in Baton Rouge, Kaplan, Pierre Part, Golden Meadow, Grand Isle and other small towns across Louisiana, often defies the stereotypical idea of an oil company photo. These photos, thanks to the artful eye of Stryker and his photographers, underscore how integrated oil was into the lives of the people it impacted – and to the culture and way of life of Louisianans.

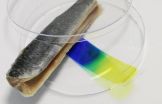

"As a native of Louisiana, I grew up in a family and in communities with deep stakes in the oil industry, so I already had my finger on the pulse of a people economically and culturally invested in oil. Now, what I wanted to do was to find a way to look behind the typical photos of a literally oiled landscape to see the faces of people who are directly impacted by even the most subtle of economic and environmental changes," said Pasquier. "When we look at the photos of oily pelicans or an oiled coastline, we should also be trying to understand the backstory that was there long before the oil spill. We should also be looking for the everyday human story that isn't drenched in oil."

Pasquier, inspired by the Standard Oil Collection, decided to look for the individuals and families featured in the original photos. What he found was that the oil industry is so intertwined with life in coastal Louisiana that it's often imperceptible to those who are living it.

"It's a complicated relationship, one that can't be simplified by looking at it through only one lens or in one photograph," said Pasquier. "It's the people, the water, the land, the coast – it's connected to many aspects of life."

Oil offered financial opportunities for some, both then and now. The economic impact of introducing petroleum jobs to an area previously dependent upon farming, fishing and other forms of agriculture, cannot be overstated. The ripple effects of the financial gains are complex and varied, accounting for a form of rigid loyalty from many of those on the receiving end.

"In the case of former employees of the Standard Oil Refinery in Baton Rouge – people who would have worked during the time that Stryker's photographers visited the facility – it's hard to find retirees and their children who speak ill of what is now ExxonMobil," said Pasquier. "It's a kind of ingrained respect for a company that provided direct access to middle class America. Not surprisingly, economic forces are hard to argue with."

Pasquier tracked down several of those featured in the Standard Oil photos, and upon interviewing them, learned a few things that might be first perceived as counter-intuitive.

But once he realized how big the story was – and how complex – Pasquier joined forces with LSU's Coastal Sustainability Studio, in order to determine the intersections between people, land and water – and oil.

"Most Louisianans feel the dangers associated with drilling are necessary for the state's economy. That's why so many people here reacted so strongly to the offshore drilling moratorium," said Pasquier. "The oil spill isn't just a one-off event. Most people know that there are environmental risks associated with the exploration, extraction and refinement of oil, but, in talking with residents, it's a risk many people are comfortable taking."

However, Pasquier said, "that isn't to say that people aren't asking themselves serious questions, ethical and moral questions, about the past, present and future of oil dependency at the local level. Many people have lost their jobs or taken new jobs, which has transformed the daily lives of some hardworking families."

Pasquier's documentary project takes him all over southern Louisiana, interviewing residents about their lives and their heritage on the coast.

"They notice cultural changes that are connected to oil. Many are dependent on oil to work, but the price of gas and the environmental costs of the oil spill have driven many independent fishermen out of business," he said. "For some families in coastal Louisiana, this is the first time anyone is looking to the future with the understanding that their children and grandchildren won't grow up in their current communities … they know all too well that their way of life is changing."

For example, every year the people of Golden Meadow, like many fishing communities in South Louisiana, conduct the blessing of the shrimp fleet ceremony. But this year, with increased fuel costs and the lasting impact of the oil spill, some of those communities have seriously considered cancelling the decades-old tradition.

"The Deepwater Horizon oil disaster harmed an already declining fishing industry, so church members were already asking themselves, 'will we do this again this year? Or the next?'" he said. "Fewer and fewer people participate, in part because fewer and fewer people are able to make a living from fishing or shrimping."

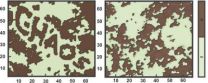

The problems of coastal erosion and land loss also hit these communities hard. In response, Pasquier and the LSU Coastal Sustainability Studio reached out in order to teach students, educate the public and work with scholars and policy makers to conduct a major research project titled "Measured Change: Tracking Transformations on Bayou Lafourche."

The project is being conducted by an interdisciplinary team of scholars committed to understanding how a resilient system of land and water management can help current residents face the future challenges that inevitably come with coastal living.

"Oil isn't just a natural resource," said Pasquier. "To understand oil, we need to understand people. With the LSU Coastal Sustainability Studio, my collaborators and I are combining ethnographic fieldwork, archival research, geospatial analysis and design speculation to understand how people live on land and with water in environmentally threatened areas."

Pasquier and his students are in the process of producing eight short documentaries chronicling some of the personal stories of the individuals they have met in Bayou Lafourche.

"We want to have documentation of this way of life, not just for our own research but also for the people of Louisiana," he said. "This kind of local knowledge is unquantifiable, but incredibly valuable."

The photos and documentaries are just a starting point, he said, toward understanding the relationships between the people, the oil industry and the environment.

"This isn't about justifying our use of oil, or being pro-oil or pro-environment," Pasquier said. "It's about assessing the terrible consequences of the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster by taking the time to focus on and understand the big picture, the realities that exist in everyday life for many Louisianans. This is about our history and our culture – this is about us and our future."

###

END